Charlie Hunnam’s Dumb-Dumbs Are Anything But Humdrum

The actor has made a career out of musclebound oddballs.

Charlie Hunnam gets a bad rap. The former model has attempted to make a name for himself as a leading man, but his unique brand of meatheadedness is quite different to the competent and suave badasses making up the A-list of action. He’s no Jason Bourne. There’s no way he’d pull off billionaire/playboy/superhero. That’s not what he’s after. His characters all — like the man himself — strain against their muscles as physical limitations to their introspective spirits. They want to be poets and writers and academics, but find themselves damned by their bodies, faces, lifestyles, and fates. In performing these roles, Charlie Hunnam has perfected the long-suffering wannabe-intellectual tough guy. He does this to great effect in the gorgeous slow-burn adventure The Lost City of Z, which expands this weekend, but first, let’s look at how he got here.

Hunnam’s career started as a beefy, rebellious pretty boy on Queer as Folk and never quite left that niche. His transition to film only solidified his place in the media world. Green Street’s terribly cockney hooligan and Children of Men’s rebellious biker allowed critics to find the common thread, focusing on his unnatural line delivery. Hunnam always seemed to be working hard to crank out the dialogue, pulling the proper mental cranks with his imposing physique. The words stuck in his mouth, unaccustomed to their brashness.

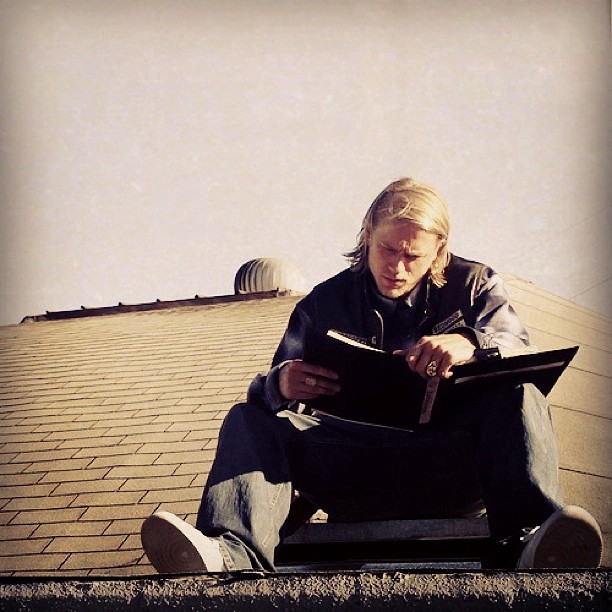

His awful Green Street accent, which was included on Telegraph’s list of the “five of the worst ‘Cor Blimey’ offenders,” seemed to scare off business. In fact, he didn’t act for an eighteen month period, during which time he wrote and sold a screenplay about Vlad the Impaler just to keep up on his house payments. But Kurt Sutter, the Sons of Anarchy creator that seems to think of himself as a similarly rough-edged artistic soul, cast Hunnam as Jax Teller and what could’ve been an unsuccessful acting career doubled-down on the things that made it watchable in the first place. Jax, the violent yet conflicted leader of a biker gang (excuse me, motorcycle club), embraces the spirit of Hunnam’s talent. He tosses grenades and stabs rival bikers but he never looks more at home than when he’s on a rooftop, floppy hair swaying in the wind, scribbling into a notebook.

Hunnam’s skill lies in, whatever the circumstance, making us believe that he’s never thought this hard in his life. Each self-reflection or considered realization feels so real because of this carefully crafted facade. His dummies are never the anti-intellectual heavies cast as bodyguards and villains. They’re curious and aware of their own educational lack.

As he moved on to work with Guillermo del Toro, a thoughtful filmmaker if ever there was one, his earthiness allowed his earnest intellectual curiosity and capacity for progressivism to be a hidden pleasure. As Pacific Rim’s Raleigh Becket, he speaks Japanese and fights for Mako (Rinko Kikuchi) to join him as his co-pilot. He also beats the hell out of some monsters, pounds some brews, and threatens assholes. He is both leading man and a guy too cinematically tough to lead. His doctor in Crimson Peak continues the negotiation of thick rube and insight, not quite a hyper-masculine savior and not quite as smart as his title may imply.

The Lost City of Z is the ultimate expression of this balancing act and Hunnam’s fascinating embodiment of it. Hunnam plays British explorer Percy Fawcett, a military man skilled at survival and stifled in the political game of peacetime military service. He’s called to go on a cartography mission into the Amazon (we find that he was always good at mapmaking back at school), finding the danger of the jungle intellectually, physically, and spiritually alluring. He’s drawn back to it, time and time again, not just to prove his theories correct about the natives and their history — which would debunk centuries of European racist anthropological theory — but prove himself worthy of the important destiny he feels he deserves. His return to domesticity in between his jungle adventures (even when these adventures become more and more treacherous) hampers him.

His loving wife and his adorable, ever-growing stable of children only cage him in further, turning Hunnam’s often maligned attributes into considerable strengths. His adeptness at being a stubborn dummy isn’t just apt for the character, it’s thematically additive for the film. His thirst for adventure and knowledge masks an insatiable thirst for personal glory that leads to his ruin. As Percy Fawcett remains drawn to the Amazon and his lost city, so does Charlie Hunnam remain magnetized to his lovable — sometimes wooden but always inquisitive — lunkheads.