Feathers and Female Transformations: Becoming-Animal in ‘Black Swan’

Darren Aronofsky’s film portrays the horror and violence of becoming a different species.

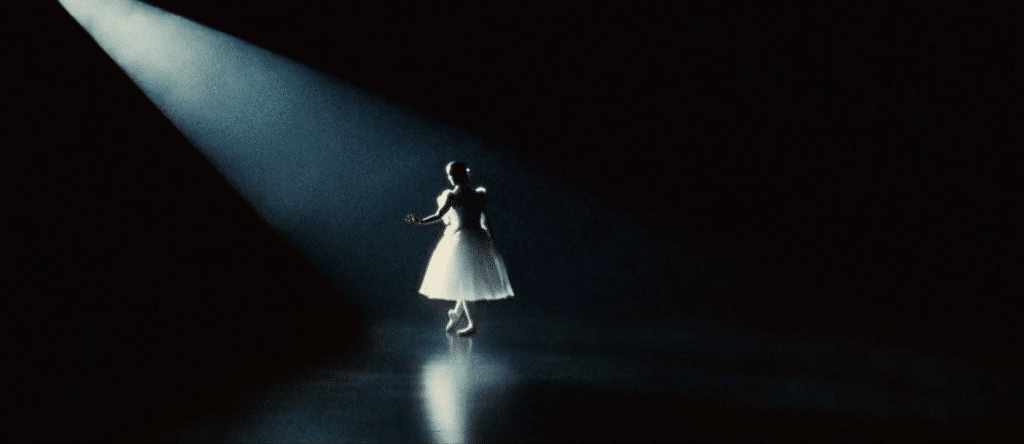

When I first watched Darren Aronofsky’s 2010 film, Black Swan, I immediately knew that it was the kind of film that required multiple viewings. Naturally, I went back to the theater and watched it again before buying a DVD copy which I have since worn out with repeated viewings. Black Swan is a dense and layered film, with so much to focus on: the theme of doubles and doppelgangers, the prominence of mirrors, the way the plot matches the story of Swan Lake, the meticulously crafted visuals, and the film’s obsession with different expressions of femininity.

However, it wasn’t until I took a class focusing on Animals in Cinema that I realized this film deals with a woman’s literal transformation into a swan. Nina’s (Natalie Portman) transformation into a swan neatly matches up with French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s concept of “becoming-animal”, wherein a human violently and painfully becomes an animal, in a shift away from their previously established identity.

In Deleuze and Guattari’s book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, they outline the concept of “becoming-animal,” which they created to describe the process of human transformation into another species. Becoming-animal is not necessarily a straightforward concept but begins to make sense once applied to works of art such as Black Swan. The concept focuses on the process of becoming, rather than on the animal become. Gerald L Bruns writes in New Literary History that Deleuze and Guattari frequently improvised concepts — such as becoming-animal — that avoid closure and resolution. Becoming-animal is a process with no conclusion, and instead of focusing on past or present, before or after, it pulls in both directions at the same time. It is a movement from unity to complexity, and from organization to anarchy. The human subject is swept away, and the subject no longer occupies the realm of stability but is instead nomadic and restless.

Becoming-animal is not merely resemblance or imitation, but rather, it is a human existing in the space between human and animal. Imitation of an animal’s physical behaviors and characteristics is an entirely different phenomenon, one that is much more simplistic than what Deleuze and Guattari refer to. “Imitation” implies playful mimicry, but Deleuze and Guattari refer to a process of literally changing one’s entire identity. Deleuze and Guattari write that this is a process of “expansion, propagation, occupation, and contagion” wherein one’s identity is radically transformed, and one no longer has a fixed identity, but rather one that is constantly changing and being renegotiated.

In Black Swan, Nina renegotiates her entire self and all of her relationships once she enters the process of becoming-swan. Nina enters into this process to leave behind the rigidly defined identity in order to become an anarchic being with no fixed place in society. Nina’s identity has been shaped by her mother (Barbara Hershey) and the way she infantilizes Nina and treats her like a little girl, as well as the fact that she is a ballerina who feels she must physically and spiritually conform to what a “perfect” dancer must be. She speaks softly and is very shy, she almost exclusively wears pink, white, and baby blue, and her room is decorated with butterflies and stuffed animals. She is extremely thin and barely eats anything, and spends all of her time working incredibly hard at ballet rehearsals. When she starts to become a swan, she radically transforms and moves away from the rigidly defined idea of “Nina”.

However, Nina’s transformation is complicated by a number of elements. First of all, Nina seems to be the only one who is aware of the transformation. The scenes where she begins to exhibit the physical characteristics of a swan — feathers, webbed feet, a long neck, red eyes, legs that bend backward — are framed as hallucinations that disappear shortly afterward. There are some scenes where she is turning into a white swan and other scenes where she is turning into a black swan — which makes sense, as she is cast as both Odette and Odile in her ballet company’s production of Swan Lake. However, this makes her transformation even more chaotic, as she is in the process of becoming two very different swans.

The concept is also complicated because the film deals with animal imitations, which, as I previously mentioned, are not the same thing as becoming-animal. These imitations are important to consider in order to differentiate between imitation and Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of becoming-animal. While Nina imitates the white and black swans when she dances, she is also literally undergoing a metamorphosis from girl to swan, which apparently only she is aware of. The other dancers in the production also wear feathery white costumes and makeup to make them appear swan-like.

The film’s mise-en-scene is filled with artistic representations and replicas of swans: there is a swan skeleton in artistic director Thomas’ (Vincent Cassel) office, his apartment has black and white swan-like designs decorating the walls, and there is a mosaic picture of a swan on the ledge of Nina’s bathtub. Nina and Lily’s (Mila Kunis) costumes and makeup resemble the white and black swans — Nina represents the fragile and innocent white swan, as she is pale and thin, and frequently wears a pink and white jacket with a feathery white scarf, whereas Lily represents the dark and seductive black swan, with her dark eye makeup and clothing and black swan wing tattoo on her back. The production’s villain, Rothbart, wears an elaborate black and green feathered costume and a prosthetic bird’s beak. These examples all represent humans imitating animals either for artistic pleasure or as part of their daily expressed identity, and stand in stark contrast to the painful full-body transformations which Nina undergoes.

Nina’s becoming-swan is much more visceral than these imitations, and at times is so violent that the film begins to feel like a horror movie. The camera constantly focuses on Nina’s body as she runs to and from rehearsals, dances, changes clothing, picks at her skin, and scratches the rash on her back, and as she begins to experience the violent transformation from girl into swan. Nina’s body is painfully contorted, and the soundtrack is filled with sounds of cracking and breaking as her body changes shape. Her eyes turn deep red like a black swan’s, and she cringes as she pulls pointy black feathers out of the rash on her back. Her legs snap backward like a bird’s legs, and she loses her balance, hitting her head on the metal edge of her bed.

She winces in pain as she realizes her toes have stuck together, becoming webbed swan’s feet. In the most dramatic visualization of her transformation, she fouettés across the stage as big black feathers cover her arms, until she takes her final bow, her arms completely transformed into swan wings. Later on, during the final performance as Odette — the white swan — small white feathers protrude from her arms, in a much more subdued version of the black swan performance. These are the ways in which her transformation is visually presented.

These representations of becoming-swan are presented as moments of body horror, signifying the incredibly dramatic nature of becoming-animal. In Linda Badley’s book Film, Horror, and the Body Fantastic, she writes that horror is one of the most physiological genres, focusing on bodily movements and spectacle. Ronald Allan Lopez Cruz writes in the Journal of Popular Film and Television that body horror is a sub-genre of horror, dealing with transgressions and complications of biology, featuring distortions of the human body.

Body horror tropes are used in the visual representations of Nina’s becoming-swan. Cruz writes that body horror often focuses on the assimilation of traits from one species to another, forming “hybrid species” which break down any traditional taxonomical classification. These species are presented as terrifying because they are formless and categorically incomplete, producing a fearful and uncertain response in spectators. Black Swan may not be a traditional horror film, but it certainly uses visual tropes of body horror to produce fear and revulsion in spectators.

In Simone Bignall’s brilliant 2013 article, “Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal”, she notes that Nina’s becoming-animal transformation changes her relationships to those around her. As Nina’s identity radically changes, so does her way of interacting with those around her. She begins to reject her mother’s possessive and controlling ways, and she begins a friendship with the seductive Lily. She has fleeting moments of sexual passion with her ballet instructor, Thomas, including one surprising moment when she bites his lip so hard that he bleeds. These new relations with others represent drastic changes in Nina’s behavioral patterns. Bignall writes that Nina feels free to engage in new behaviors — going out dancing and taking drugs with Lily, locking her bedroom door, staying out late — because the process of becoming-swan has begun to expand her identity.

Bignall notes that becoming-animal occurs when an individual rediscovers its form as a multiplicity, rather than as one fixed identity. Deleuze and Guattari believe identity is composed of multiple elemental parts arranged in complex relations. Bignall writes that Nina’s previous elemental parts include “dancing, music box, shyness, broken toenail, ambition, frigidity, plush toys…”, but that once she begins the process of becoming-animal, she is confronted with the fact that she is more than these things. She is no longer a fixed individual, but a complex one that cannot be rigidly defined. Bignall explains that becoming-animal involves the dissolution of the individual along with the forging of new and complex connections to others, which is exactly what Nina experiences as her identity changes.

Black Swan ends with Nina’s demise after she stabs herself with a shard of broken glass and dances to death onstage. I will note that it is left ambiguous whether or not she actually dies, but she is essentially mentally and physically destroyed by the time the film fades to white at the very end. Nina is not able to successfully reside in her state of becoming-animal, and her attempt to escape from her rigidly defined feminine identity is tragically fatal. Bignall writes that the process of becoming-animal may be radically disabling and end up completely destroying one’s subjective experience and physical form — which is of course what happens to Nina. She descends into madness and becomes detached from her body and her sense of self. She hallucinates that her mother’s paintings laugh at her, she imagines that Beth (Winona Ryder) stabs herself in the face and follows Nina home, and she fantasizes about a passionate sexual encounter with Lily which she believes actually happened. As Nina moves further away from her past identity and becomes a “hybrid species”, the more she loses her grip on reality and her own body.

Bignall notes that Deleuze and Guattari account for the dangers of becoming-animal, especially when the process is so disruptive of one’s existing set of relations that the self is completely abolished, which essentially happens to Nina. Deleuze and Guattari propose that one must be cautious during the process of becoming-animal not to leave behind one’s identity too quickly, before considering the possible consequences. Nina’s fearful and anxious personality does not allow her to stop and think rationally about anything that is happening to her, so she continues radically leaving behind her sense of self, with tragic results. Bignall writes that Nina’s transformation is radical and catastrophic, ending with her personal relationships, subjectivity, and physical body all in shambles and completely unrecognizable.

Natalie Portman gives one of her best performances in Black Swan, recalling the tragic and anxious performances of Catherine Deneuve in Repulsion, and even Sheryl Lee in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. What sets Black Swan apart from these other films dealing with female anxiety and loss of identity is that Nina also literally begins to become a swan onscreen. This process moves the film from being a psychological thriller to being a body horror film at times. Nina suffers through a violent and gruesome transformation from girl into swan, and at the same time leaves behind her old sense of self. She experiences pain and terror, but in the process, she also experiences sexual ecstasy, and feelings of freedom and perfection, particularly when she dances as Odette and Odile in Swan Lake.

Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of becoming-animal is very abstract, but one of the greatest things about cinema is how strange concepts begin to make sense when applied to films. It is tragic that Nina is unable to completely free herself from her old identity in the end, but her violent ending is also tinged with triumph as she whispers: “I felt it. Perfect. It was perfect.”