A Brief History of the ‘Hangout’ Film

More than a sub-genre; a way of life.

Filmmakers have worked within recognizable genres for nearly as long as they’ve told stories. Initially film appropriated genres from literature and theatre, but as the new medium found its footing in Hollywood’s Classical Era of the 40s and 50s, a distinctly cinematic set of generic conventions were codified. Since that time, genres have come in and out favor, but most new films have still defined themselves either in accordance with or opposition to the Classical Hollywood models. Even innovative filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard and David Lynch have self-consciously manipulated the language of genre, treating it like another tool in the director’s toolkit. But films are living things, and there are as many ways to draw the lines of categorization as there are films. Reevaluating movies of the past according to new and different models is one of the best ways to keep the medium from ossifying. In that spirit, I’ll endeavor to lay out a set of conventions for one such model: the hangout film.

The term “hangout film” was first coined by no less masterful a genre manipulator than Quentin Tarantino, most notably in Larissa MacFarquhar’s vivid New Yorker profile. Not unlike landmasses, unexplored genres are defined by their discoverers. Here’s Tarantino’s take on the hangout movie:

“There are certain movies that you hang out with the characters so much that they actually become your friends. And that’s a really rare quality to have in a film…and those movies are usually quite long, because it actually takes that long of a time to get past a movie character where you actually feel that you know the person and you like them…when it’s over, they’re your friends.”

MacFarquhar summarizes that hangout movies are those “whose plot and camerawork you may admire but whose primary attraction is the characters.” This is not quite the same as the character-driven film, nor the ensemble picture. Taxi Driver is not a hangout movie, nor is Spotlight. Mere length isn’t enough to define a hangout picture either: Schindler’s List decidedly does not qualify. Rather, the hangout film is characterized by a certain lightness of tone, and — perhaps most crucially — a languid, almost meandering pace. The familiarity bred by the hangout film is that of the dorm room, the small high school class, or indeed the film crew; it arises not through action but through downtime, the spaces in between events.

Tarantino first deployed the term in reference to Howard Hawks’s 1959 Western, Rio Bravo, and if any film is the standard bearer for “hangout” style, Rio Bravo is it. Clocking in at 2 hours 21 minutes, the film nominally concerns the efforts of Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne) to hold a local outlaw’s brother in jail (forming the inspiration for Assault on Precinct 13, not a hangout movie). But this “plot,” such as it is, doesn’t materialize until nearly an hour into the film, by which time we’ve already gotten to know a lovable cast of characters that includes a wily old cripple named Stumpy (Walter Brennan), a quick-witted woman named Feathers (Angie Dickinson), a handsome young cowboy named Colorado (Ricky Nelson), and a noble drunk known only as Dude (Dean Martin).

The film scholar David Bordwell notes, in a reverent piece called “The Tao of Rio Bravo,” that these nicknames help to situate the film outside the strictures of realism and into the mode of a mythic text. He writes:

“Far from being an accident, the names in the Sacred Text are there to impel the Initiate into deeper mysteries. Is, for instance, Stumpy The Elder called Stumpy because of his lameness — always a sign of grace in sacred texts? Because of his inertness (as stiff as a stump)? Or because a tree, even though harvested, retains its attachment to the earth by remaining rooted? Perhaps He Who Is Called Stumpy is “grounded,” as the current saying has it…She Who Is Called Feathers wears feathered clothes, but also has a teasing lightness of manner. He Who Is Called Dude constitutes a crux. Is he a “dude,” an Easterner who has come west, or is he a dude because he favors fancy outfits?…The central fact is that in this text, the mystery of naming opens on to the Mystery of Being. Everyone is named something, but many are not named by their name.”

Bordwell’s tone is playful of course, but the style of the hangout film often invites such mystic readings. The Big Lebowski, another classic of the hangout genre, is revered by many as a paragon of Zen wisdom. Jeff Bridges even co-authored a book with Zen master Bernie Glassman on the timeless wisdom of film’s central character (likewise known only as Dude). Characters in hangout films are prone to making deceptively sage pronouncements, often disguised as throwaway lines. From Big Lebowski: “the dude abides.” From Rio Bravo: “Just stop talking. Just let it be.”

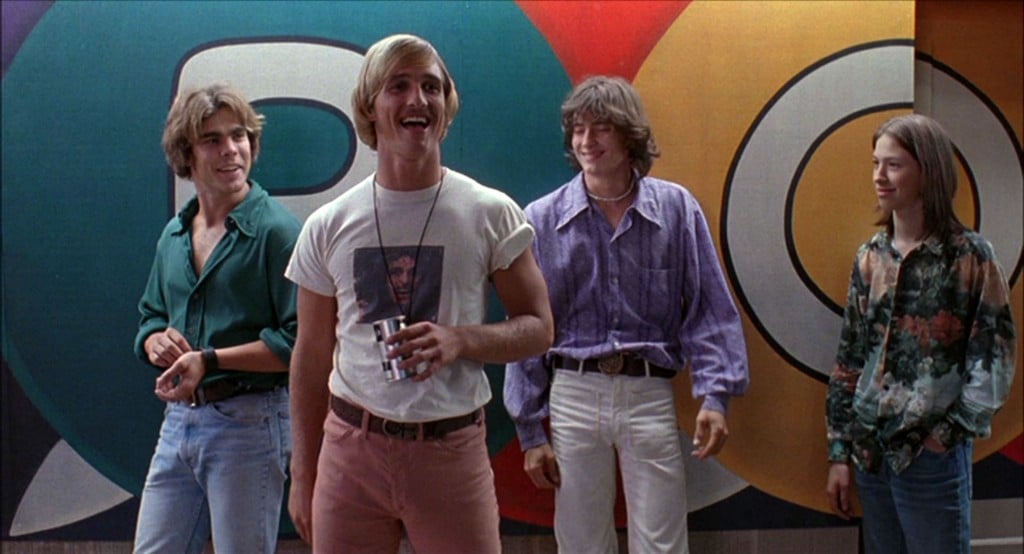

Some directors have made a career on the hangout film, most notably Richard Linklater. Beginning with Slacker in 1991, Linklater’s films have helped to solidify not only the tonal attributes of the hangout film but also its philosophical underpinnings. One does not so much watch a Linklater film as float down its river, acquainting oneself to its characters and musing alongside them about the nature of love, life, and time. Indeed, the exploitation of the element of time is one of the things that makes the hangout film uniquely cinematic. Films like Before Sunrise and Dazed and Confused are unrushed. They draw us in not through the intricacies of plot but the power of good conversation. Their strength lies not in conflict but in presence. As the character played by Linklater himself says in Waking Life, “there’s only one instant, and it’s right now, and it’s eternity.”

Unlike the traditional, narrative-driven film, the hangout film doesn’t rely on tension to maintain interest. Goal-oriented characters with burning wants and needs are traded for principled ones who are just trying to get by. This difference is not merely a matter of narrative strategy; it’s a different view of life. From the standpoint of the hangout film, goals and conflicts aren’t the substance of life but a distraction from it. The emphasis is shifted from action to reflection, from doing to being. These films take to the extreme the old cliché that “it’s about the journey.” Road pictures, for this reason, often make great hangout movies.

One other quality unites nearly all hangout films: the use of music. Whereas most movies use music to drive the narrative forward and make up for lagging pacing, hangout movies often bring the narrative to a halt to allow the characters and audience to relish a particular track. Dazed and Confused, The Big Lebowski, and Tarantino’s Death Proof and Jackie Brown all feature such interludes, but as ever the prime example is Rio Bravo. At the height of the drama, when another film would feature characters loading their guns or preparing their defenses, the characters in Rio Bravo break into song. It’s one of the most bizarre, and bizarrely satisfying, moments in cinematic history. And as with all the great scenes in hangout films, it’s an in-between moment — one that catches the characters and the audience off guard.

So where does the hangout film fit in the latticework of film genres? As we’ve seen, it can overlap with almost any other genre: the Western (Rio Bravo), the noir (The Big Lebowski), the horror film (Death Proof), the comedy (Dazed and Confused), and the romance (Before Sunrise). In that sense, the hangout film might more aptly be called a style, like neorealism or poetic cinema. But uniquely among sub-genres, the hangout film designation also contains a qualitative judgment: to truly be worthy of the name, a hangout film requires that we come to love the characters, and by extension the film itself. The masters of the hangout film have discovered something integral about what makes us feel at home in one another’s presence, and at peace with the flow of life. We’d do well to learn from them.