Welcome to Commentary Commentary, where we sit and listen to filmmakers talk about their work, then share the most interesting parts. In this edition, Jeremy Kirk listens to Christopher Nolan talk about his still-excellent Memento.

!Commentary Commentary weekly your to back Welcome

See what I did there? This week, we’re hitting up one of the finest pieces of cinema in the last 15 years and hearing from the uber-intelligent man behind it. The film? Memento. The director? Christopher Nolan. In this commentary, you’ll uncover mysteries, technique, and styles the filmmaker put into one of his several masterworks. What you won’t be getting is any information on Dark Knight Rises. Sorry, but me just including that title here ensured 54 more hits. It’s a proven fact. So, without further ado, here is what I learned from listening to Christopher Nolan’s commentary track on Memento. In addition, I also learned a thing or two about my own short-term memory problems. Yeah, I have some trouble remembering things. Like that time I took a picture of Joe Pantoliano’s corpse.

See what I did there? This week, we’re hitting up one of the finest pieces of…Oh, never mind!

Memento (2000)

Commentators: Christopher Nolan (writer, director)

- Okay, the Christopher Nolan commentary for Memento is creepy pretty much from the damn beginning. His voice comes in as the image Lenny holding the photo comes up, but the voice is slowed down and partially backwards. It quickly corrects itself, but thanks, Nolan, for putting me on edge while I’m trying to work.

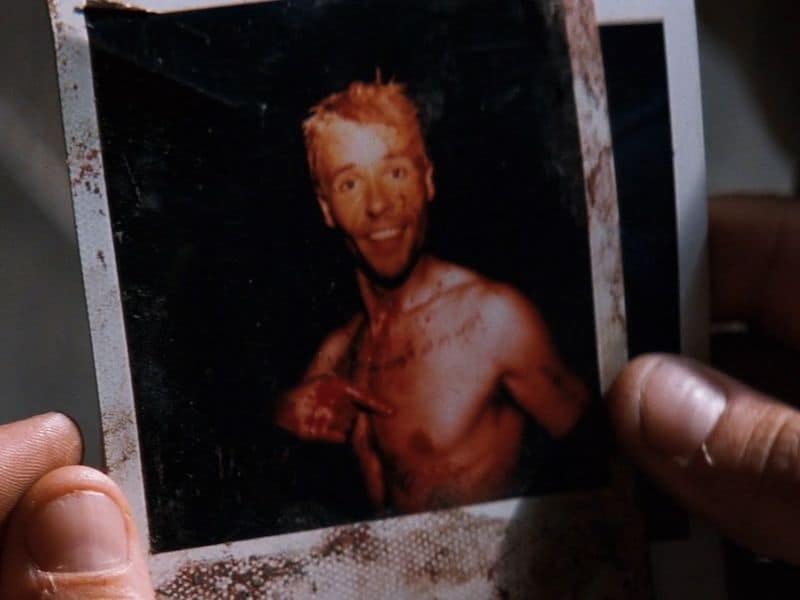

- The opening image was designed to immediately pull the audience into the film. The idea of the image coming backwards and the Polaroid picture fading out came late in the filming process.

- Even though the images in the beginning of Memento are running backwards, the sound runs forward. Nolan notes he did this to keep some kind of convention to the opening moments to help draw the audience into the story. All of the shots in the opening were done using a reverse mag, essentially the film was loaded in backwards, except for the image of the shell casing moving across the floor. This was done by Nolan blowing on the casing.

- The idea of shooting the “present” sequences in black and white was to give the film a documentary feel. Much of the black and white sequences were shot documentary-style, as well, with Guy Pearce improvising dialogue and Nolan and editor Dody Dorn cutting everything tightly. Nolan mentions the documentary feel allowed him to give the audience an objective view of Lenny’s character. He wanted to put the audience in Lenny’s mindset, to show right from the start how people might control and manipulate him. Also, like Lenny, the audience is put in a position of quickly trying to assess Teddy’s character and what the manner of their relationship is. Later on in the film, the black and white scenes moved from being objective to more subjective like the color scenes. These later black and white scenes are designed more to put the audience in Lenny’s emotional state rather than give information.

- The slow push-in on the abandoned building near the beginning was done intentionally, as a similar movement would be reused later in the film at the same location.

- For the first “loop,” as Nolan refers to each scene, the director wanted to throw in all the main elements that would make up Lenny’s character as well as the idea of repetition with a very jarring and memorable image. “With this first loop in time, we wanted to have something truly unforgettable. A gunshot to the head seemed about as good as you can get.” Nolan also mentions a key element to each loop was in the sound. He wanted to create a distinct sound for the end of each loop, Teddy knocking on the door to the motel, Lenny putting the clip into the gun, to give each section its own identity. Later in the film, Nolan used fragments of scene to transition, as the audience would then be comfortable with the film’s rhythm.

- “If M.C. Escher was going to design a motel, this would be it,” says Nolan about the motel where Lenny is staying. He notes the motel has a closed courtyard that keeps you from being able to tell where you are. The glassed-in lobby also forced Lenny to interact with the clerk.

- With the first interaction we see between Lenny and the motel clerk, Nolan was able to do several things. The scene allowed Lenny to spell out exactly what his condition is, the dialogue from the clerk indicates the condition and the way the film structurally works are connected, and it allowed them to hint at Lenny’s background. “That’s what’s most frightening for Leonard,” says Nolan. “The continual impression that he’s had an interaction with these people before that he can’t tap into.”

- Nolan was fascinated by the idea of Lenny’s past self and his present self conversing, something that was a key element to Jonathan Nolan’s short story. “I was fascinated by the idea that somebody who could not create these memories would essentially be divided by the past self and the present self, that connection between those two aspects of himself would be broken.”

- The interior of Lenny’s hotel room was a set. Nolan notes how expressive but realistic production designer Patti Podesta made the room, as the director wanted to make a “true update to a film noir.” Likewise, he had cinematographer Wally Pfister keep the light from the windows in an effort to make the room feel more realistic.

- Nolan mentions during the scene where Lenny is discovering his tattoos that the more obvious way to play it would be total surprise, but, as he notes, that wouldn’t be true to what the film says about memory. “What the film says is that you can take on knowledge unconsciously through repetition, through habit.” The same angle on this unconscious knowledge is seen later in the film in Stephen Tobolowsky’s performance, particularly in the scene where Sammy’s wife gives him his final test.

- Each correlating color and black and white scene have parallels to them about what is going on in the scene. This reinforced certain images and moments to the audience.

- Nolan feels that someone with Lenny’s condition would cling onto the long-term memories they have, so he wanted to show early on the value Lenny puts on the fragments of memory he has about his wife. Nolan also wanted to instill a true feeling of memory of a loved one, showing pieces of a person rather than coherent scenes.

- If you pay attention, the camera is always a little closer to Lenny than it is to the person he is speaking with. This is another way of getting the audience into Lenny’s head without using first-person shots.

- To reiterate how memory changes things, some overlapping shots between two loops used different takes while others used the exact same shot.

- Nolan brings up the question people have about Memento about how Lenny knows he has a condition if he has no short-term memory. According to N0lan, the film presents a theory on memory that information can be absorbed in various ways. He wanted to present a number of different ways in which Lenny absorbed such information.

- Nolan wanted Carrie Ann Moss’s character, Natalie, to be as inexplicit as possible. Her picture is fuzzy, and the information on the back of it is extremely vague. Also, the scratched out information is one aspect indicating how flawed and undermined Lenny’s system can be.

- The scene where Lenny is explaining to Natalie the different ways his memory works incorporates actual ways in which Christopher Nolan had explained the project to people before shooting. The idea of knowing how a wooden table would sound when you knock on it and other “feel of the world” aspects allowed Nolan to get people into Lenny’s head when he was describing it.

- The monologue Lenny gives regarding what he feels about his condition was originally much longer in the screenplay. Guy Pearce was very insistent in slimming it down, and while certain scenes could not be removed because of the structure of the film, this moment was somewhat expendable. “Leonard is a blank slate to a certain degree. We do sort of project things onto him, but we need something to hang onto. We need to see his view of himself.”

- Originally, the entire Sammy Jankis story was told in one scene. However, Nolan felt the story and the Sammy Jankis character was so important that it needed to be spread out over the course of the film’s middle section.

- Nolan wanted to bring in a lighter mood throughout the middle of the film. He felt it was important to switch up the tone to keep the repetitive nature of the film’s structure from becoming tedious. The director also wanted to bring in some of the trappings of an action star having to cope with the burdens of short-term memory loss. Hence the moment where Lenny smashes in the door to the wrong motel room.

- Nolan addresses the question some people have about how long Lenny can keep hold of certain memories. “He can keep things in mind as long as he pays attention, so depending on how much is being thrown at him, that time-span can vary.” Nolan also states that throughout the middle of the film, while numerous things are happening, Lenny’s memory gets shorter and shorter.

- The scene between Sammy Jankis and his wife, Stephen Tobolowsky and Harriet Sansom Harris, was only scripted in broad terms, since it was always intended to be shot with voice-over. The actors had to improvise much of the dialogue.

- Many of the scenes with Lenny and his wife, played by Jorja Fox, were meant to evoke a sense of a realistic relationship, not necessarily an ideal one. Nolan felt most of the memories Lenny would hold on to would be the bittersweet interactions that create a very real marriage.

- There was a lot of questioning during filming in the relevance of the scene between Lenny and the prostitute. However, Nolan felt it important to show a moment of Lenny manipulating himself, “his present self creating a situation for his future self to arrive at,” as Nolan explains. The actors during filming weren’t exactly sure how to wrap their performance around the scene, as evidenced in the very real awkwardness that plays out between the two of them.

- The idea of Mrs. Jankis hiding food around the house to cause Sammy to remember where it was hidden through hunger interested Nolan. It was initially fleshed out in an early draft of the screenplay, but in order to strip the story down further, it was lost.

- Nolan loves how Teddy randomly pops up unannounced, as if there is a whole side story that we’re not seeing. Teddy already being in the car when Lenny gets in at one point was Joe Pantoliano’s idea.

- Continuity comes up in Nolan’s commentary, the idea that when dealing with unusual structure it becomes very tricky handling distinctions in the continuity to keep the audience from becoming disoriented. Nolan mentions how tricky it was to decide the importance of some continuity aspects over others. The cleanness of Lenny’s clothes and the age of the wounds on his face are specific examples Nolan points out.

- When Lenny writes “Do Not Trust Her” on the back of Natalie’s photo, he uses a different style of handwriting than everything else he writes. This was deliberate and Guy Pearce’s idea, since Lenny would inherently be suspicious of Teddy telling him to specifically write that. This difference in handwriting is an indication to Lenny from himself that it is a message he would later scratch out when Teddy was out of view.

- The blood coming out of Lenny’s head when he is hit by his wife’s attackers was Guy Pearce’s idea, as well. Nolan thought it would be a bit too much at first, but then acquiesced to it after seeing it shot. “It felt like his mind leaking out. It felt like the end of his past self.”

- And then comes the 1h33m mark on the director’s commentary. Basically, there are four different commentaries that play over the last 20 minutes of the movie. The first one is accessed if you skip ahead to within these last 20 minutes with the commentary on or if you turn the commentary on after the 1h33m mark has been passed. The remaining commentaries are accessed playing the commentary track from the start. Once the 1h33m mark hits, we jump randomly to one of three commentaries, each slightly different from one another – the big differences come as Lenny is dragging Jimmy down the stairs – but with different indications about Teddy’s character forcing, as Nolan always so masterfully does, the viewer to come up with their own conclusion.

- FIRST ENDING: The commentary continues as normal with Nolan describing the blocking of Lenny walking down into the motel lobby and meeting Teddy. Nolan mentions the film is loaded with “direct repetitions” and “echoes” that creates kind of a deliberate confusion in the mind of the audience to keep the audience on their toes, to keep them second-guessing what they have or have not seen. These two points are the same with the other three commentary endings, too. However, on this track, once Jimmy shows up at the abandoned building, Nolan’s voice drops out, slows, and starts playing in reverse. The commentary plays backwards for the last 15 minutes.

- SECOND ENDING: Nolan feels it’s important to come to a scene of exposition where a disreputable character lays everything out and answers a lot of questions. Nolan likes how with the structure of this film, the audience would be at a different mind-set about whether or not to believe this explanation. A lot of work went in between Nolan, Pearce, and Pantoliano to get in as much information in the smallest amount of time possible. Nolan also points out that Joe Pantoliano filmed the scene at the end of the movie with a badly hurt back, which he sustained filming the shot where he is shot. The director mentions it is important to realize this scene is one of several similar conversations Teddy has had, but Lenny, like the audience, appears to be having it for the first time, that this information is life-changing for him but monotonous for Teddy. Nolan mentions that SG13 7IU, the license plate number Lenny writes down at the end is the postal code for the school where the director went as a boy.

- THIRD ENDING: After a dozen attempts – you think I’m exaggerating? – I still couldn’t get access to the third of the four endings to the commentary. If the other tracks are any indication, the information Nolan provides isn’t that different. However, I do know it’s on this track where Nolan reveals Teddy is telling Lenny the truth about what really happened to his wife.

- FOURTH ENDING: It’s in this commentary where Nolan reveals how untrustworthy Teddy is. Nolan points out plainly that Teddy is a liar, has been lying through the whole film, and he has known Lenny for so long that he knows how to effortlessly push his buttons and get Lenny to do exactly what Teddy wants him to do. “What’s interesting to me in terms of genre is that this scene of exposition occurs in so many other movies. It is a fairly standard device that the bad guy comes along at the end of the movie and gives us the exposition, and to me it’s amazing that people don’t question that character. They just accept the answers because they’re so desperate for answers in the story.”

Best in Commentary

“That was the key to the structure, withholding the information from the audience that’s withheld from Leonard, ie. what’s just happened, but allowing them to tap into his desire to move forward and get some idea of what he’s going to do next.”

“Any narrator is potentially unreliable, but this is a narrator who is very clearly unreliable and knows it himself and explains it to the audience. It seemed very essential to represent that to the audience.”

“That was one of the attractions to the story, that you’re going to continually be able to have a moment of discovery, a fresh moment of discovery. You’re continually going to be able to shift gears and be somewhere completely different for the audience.”

Final Thoughts

With soft-spoken, almost flat delivery and a British accent, Nolan sounds exactly like the genius we all hope him to be. Some of the commentary can come off quite dry, particularly since much of it deals with the film’s logic and structure. The Memento commentary seems more from the perspective of its writer rather than its director, but there’s nothing wrong with that.

Just hearing Christopher Nolan talk story design for nearly two hours is engrossing enough. It doesn’t even really need that catch – some might call it gimmick? – with the alternate endings and tiny bit at the beginning where it runs in reverse. But, since it’s in there anyway, it just adds to the captivating experience. Excellent film. Excellent commentary, and I could have listened to four more hours of it.

Read more Commentary Commentary from the archives.