Dipping his toes into romance, coming-of-age, and thriller, Louis Malle covered a lot of ground during his reign in French cinema. He is one director who was not afraid to embrace the limitations of a specific genre, using them to test himself as a filmmaker. Whatever story he told, he poured himself into and didn’t merely deliver an experiment in genre filmmaking. As his pivotal thriller Elevator to the Gallows turns 60, let’s take a look at the noir style it embraces while taking on a French narrative.

Elevator to the Gallows follows Julien (Maurice Ronet), a war veteran and businessman, as he kills his boss, Mr. Carala (Jean Wall), and runs away with the man’s wife, Florence (Jeanne Moreau). The plan goes awry when he goes back to retrieve evidence he left behind and gets trapped in the elevator. As Julien tries to escape, a couple of young teens steal his getaway car and leave another trail under his name to another vicious murder he didn’t even commit. The police are dumbfounded and so is Florence, but she is determined to find the truth and hopefully get her lover out of trouble.

The best of noir

Malle chose the very best noir elements when constructing the style for Elevator to the Gallows. Many American films noir could only have wished to have a score as well-rounded as the one Miles David created here. The number that plays as Moreau walks down the streets of Paris is what everyone imagines when they think of the genre: dark, smooth, and sexy, the brassy sound of a trumpet cuts through the dreamy, soft light that illuminates the actress in one of her most famous scenes.

In that moment, we’d expect a typical noir voiceover, but no need for one with the score that gives us a lonely monologue without ever uttering a word. Not every number in the score is slow. Davis picks up the pace with the scenes that follow the young French couple during their adventure. As spontaneous as their plot, the jazz that scores their moments is quick and jumpy.

One of the prime signifiers of a film noir is its cinematography. Shots drenched in shadows help create the ambiance of a dark crime story, which Elevator to the Gallows certainly has. Whether he is using the vast spaces of a freeway or the cramped dark elevator, Malle uses light in noir fashion — to create beauty in the darkest of places and in the vilest of stories. The historic streets of Paris are turned into a modern, neon-booming metropolitan city reminiscent of New York City. The bars, tobacco shops, and other places Florence (Moreau) wanders past in the night could pass for American if not for the signs plastered outside of them being in French.

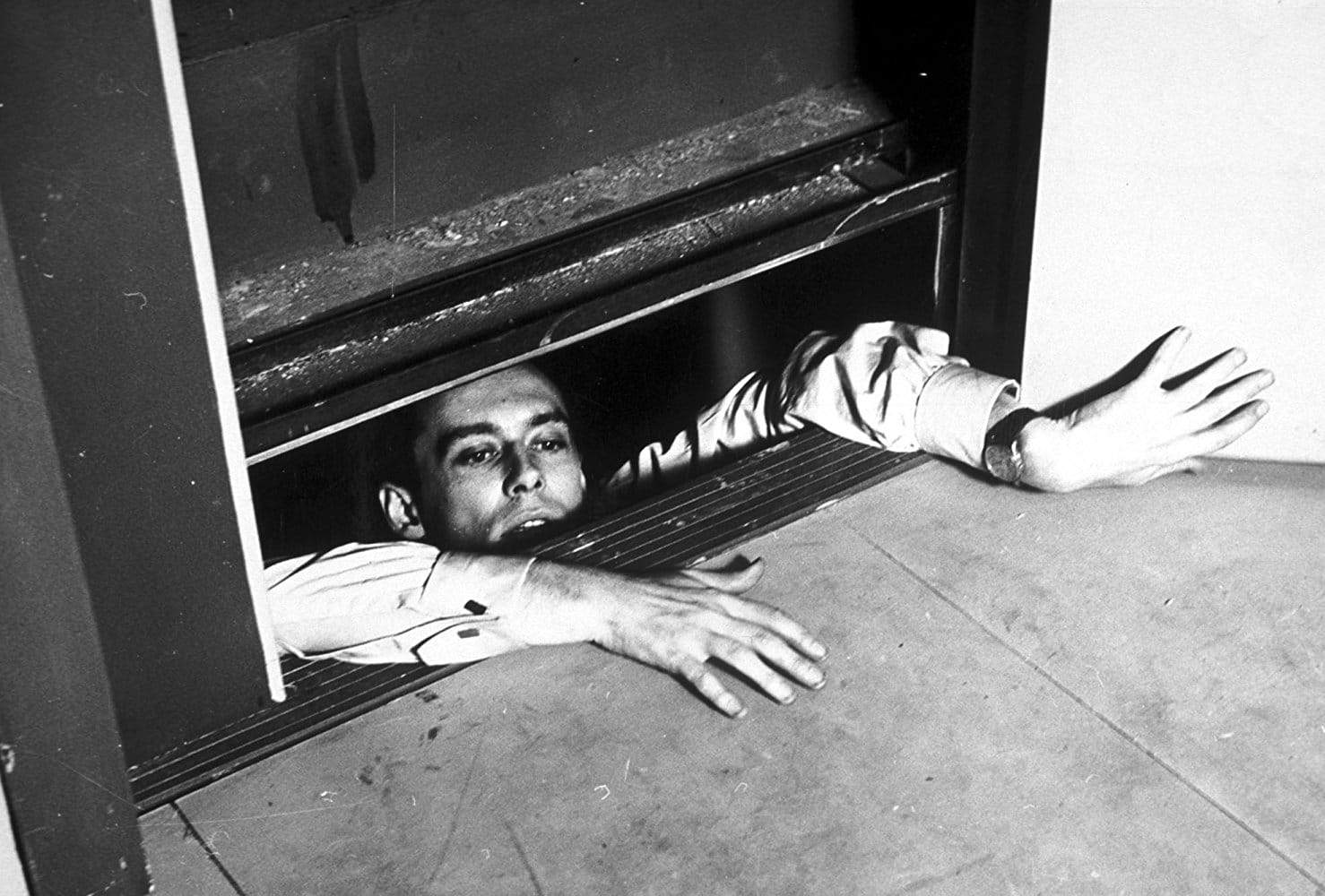

The claustrophobic spaces Julien finds himself in benefit from the high dark and light contrast that is common in noir. The elevator, either lit by a lighter or the flashing lights of an alarm, is an obviously small space in the way it was lit. The interrogation room Julien finds himself in the end is a black void, the only lit objects being the investigators and a single table. As each person moves out of the light, they get swallowed by the blackness that surrounds them, making it look like Julien truly has nowhere else to go at that point in the film. We find out soon enough that he doesn’t.

Another aspect of film noir comes through in the story, with the men of Elevator to the Gallows embodying genre tropes. Julien is the cool, calculated killer. Even though his plan is in the name of a passionate love affair, Julien seems emotionless in his murder of boss Mr. Carala. His plan is perfect, that of a man who has done this before. We learn from onlooker Veronique, that Julien is a product of war, considered a hero by many. His experience and coldness feel like that of a hardboiled male, save for his love for Florence. His plan goes horribly awry, but he still maintains his collected attitude until the very end.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is young and wild Louis (Georges Poujouly). He embodies the brooding, reckless character that is a part of several noirs such as 1949’s They Live By Night. He and his girlfriend Véronique (Yori Bertin) contrast Julien and Florence completely. They act together, passionate lovers just looking for fun and getting mixed up with murder. They think they are ready for danger until they confront it head-on with the consequences of their actions. They crumble into tragedy, accepting the fate of tragic lovers. Louis tries to be the tough character Julien is, but his actions are never calculated. Louis’s plot is the dangerous outlaw story we adore in noir films and know will not end well.

Hardboiled literature and film noir were born out of hard times. They highlight the deteriorating society, either the underbelly of a busy city or the corrupt high class. Like any Raymond Chandler novel, Elevator to the Gallows attempts the same take on French society. As Terrence Rafferty discusses in his essay for the Criterion Collection, Malle wanted that take to be a part of every storyline:

Malle later said of ‘Elevator to the Gallows,’ “I showed a Paris not of the future but at least a modern city, a world already dehumanized,” a statement that, I think, serves as a useful description of the film itself: not of the future but at least modern. Some of that modernity is on the surface—in the “automated” paraphernalia of the office and the motel, in the glass-and-concrete boxiness of the Carala building, in the sleekness of Julien’s sports car and suit. What’s most deeply modern about the film, though, is an undertone of war weariness and general cynicism, which is most evident in the character of Julien, a veteran of France’s recent wars in Indochina and Algeria.

Just as Chandler aimed to give a cold look at the problems of America in the 1930s, Malle took what he considered to be a fatal aspect of French society, war, and showed its consequences in Elevator to the Gallows. Talk of war comes out of the mouths of several characters throughout the film. Before Julien kills him, Mr. Carala warns Julien and the audience, “Don’t sneer at war.” In the conversation with the German tourists, Louis talks about the Algerian war. A typical young rebel, he is against it. That residual hatred for Germans after World War II is present in the story, as well. They are murdered, and people in jail are almost glad. The war theme is made the undertone, while the star of the film is the crime, but it highlights the political climate in France during the 1950s like film noir did during its reign with Los Angeles in the 1940s.

A French twist

What I consider to be the French take on this inherently American genre is the way the story is constructed. We begin in what would very well be the midpoint or climax of a regular noir. Julien is about to go through with the murder he has been planning with Florence for presumably a while. All we get of their relationship is an emotional phone call. Malle does this so well, we don’t need the long backstory shown to us. We know they are in love and now we can get to the exciting part.

“All of Louis Malle, all his good qualities and faults, was in ‘Elevator to the Gallows.’” – François Truffaut

What fuels this film are the mistakes that follow. The thrill isn’t in the planning or the violence of the crime. It’s the consequences of the crime that create the tension and suspense. This take feels somewhat new compared to classic noirs. Typical of French directors, Malle took the best elements of the genre and turned the structure on its head. Veronique and Louis, who we think have killed themselves in the name of love, are not actually dead, but the key to the police’s investigation! Florence transforms from a helpless lover and takes the investigation into her own hands. These twists and a change in the structure are what make Elevator to the Gallows one of Malle’s best. Sixty years later, the film shows us the legendary style of one genre and the story of an innovator.

Related Topics: Anniversary