As part of our coverage of the 80th Venice International Film Festival, Lex Briscuso reviews Bradley Cooper’s latest, Maestro. Follow along with more coverage in our Venice Film Festival archives.

The flailing of arms. The thrashing of the head. The crisp, sharp punch of the downbeat. In the latter half of Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, the titular virtuoso, Leonard Bernstein, gives his entire body to the act of conducting an orchestra. He bends and contorts himself in service of the story being told by his musicians, his face dripping sweat and his hair frizzling in the fury of his surrender. But he unsurprisingly seems to give his heart and soul, too. He grins as the piece crescendos. He sighs as it melts into a pianissimo whisper nearly too quiet to hear. He breathes the music in through the nose, out through the mouth, and again, on repeat, until the last note is played. And then, he sees her watching—and when they embrace, their first following a fight about Bernstein’s complicated sexuality, she whispers to him that he has no hate in his heart. And how could he when it is already filled with beautiful music?

She is Leonard’s wife, Carey Mulligan’s Felicia Montealegre, the woman Bernstein had a complex yet loving relationship with for 27 years. Their marriage has long been the source of much curiosity, particularly because of how it coincided with the tricky tightrope walk of being a gay or bisexual man in the 1950s. Cooper, who also plays Bernstein, chooses to focus on this aspect of the maestro’s life with this Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese-produced biopic, using his work as a conductor as a parallel for the ways we try to conduct and control our emotions and, to a greater extent, the fabric of our lives. Ultimately, the film is a somewhat average tribute to a prolific musical theatre legend, one that gives very few flowers to that side of his career—which is strange considering it is arguably what he is most famous for in the mainstream. I mean, hell, he’s arguably the most foundational part of the creation of “West Side Story,” one of the greatest American musicals ever written.

His musical theatre era spanned the most active years of his career, throughout the latter half of the 1940s and all of the 1950s. His work on “West Side Story” is prolific, but his lesser works for the stage—”On The Town,” “Wonderful Town,” and “Candide”—are still considered some of the strongest of that period in theatre history. While Cooper chooses to use musical theatre staging to make flighty cuts between locations and scenes as the early whimsy of Bernstein’s career and relationship take off, he all but throws that creative tactic away after the film’s first half hour. The film takes on a more conventional style from there on out, and in a way, it loses the boost of charm those scenes provide.

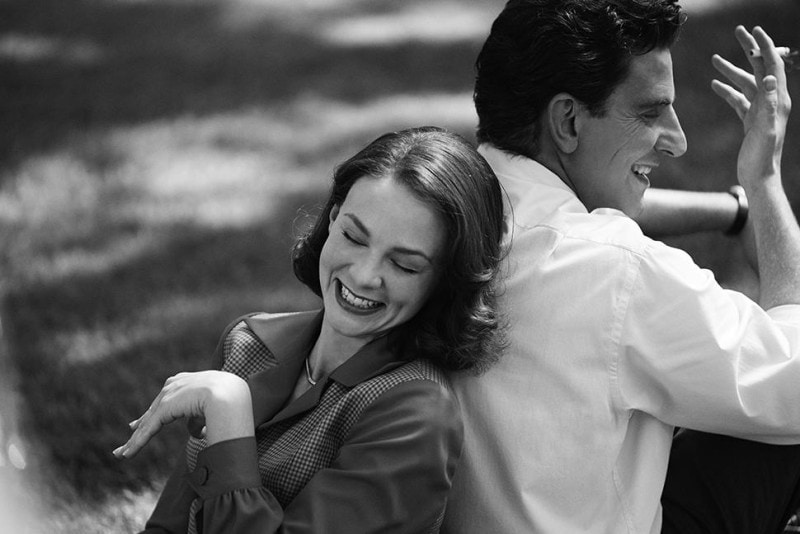

That said, the chemistry between Cooper and Mulligan revives some of that charm and repurposes it into the film’s central human connection. Bernstein and his wife connect over their love of art and performance, and their banter is some of the most natural and vivacious dialogue of the entire film, even as their relationship approaches its twilight years, where things between them are strained. Cooper and Mulligan do a lot of heavy lifting with this film, and their performances are not to be ignored by any means because the movie’s brightest points lie in their laughter with one another and the way they tenderly conduct their love like a symphony.

The film is at its strongest when Cooper is playing the conducting scenes, of which there are several, and allowing himself to be lost within the act. That much is certain when you see the emotional life within his eyes, movements, and breathing. It’s palpable, but it can’t be everything because that alone does not a good film make. Similarly, Mulligan doesn’t hold back with her performance, and it will almost certainly make for another Oscar nomination—however, it’s hard to ignore that she’s playing a Chilean-Costa Rican woman. In fact, with that knowledge in one’s back pocket, her casting somewhat distracts from the great work she’s doing, especially as the film’s focal point through Bernstein’s eyes.

While Cooper’s directing isn’t nearly as much of a standout as his debut with A Star Is Born, the script he penned alongside Spotlight screenwriter Josh Singer is well-written and fun to listen to. Bernstein’s sweet sense of humor is captured so well, and his dialogue, in particular, gives real insight into his two selves: the one he is in public and the one he is at home. It’s an effective script that begs for the kind of excitement and pacing those electric musical theatre-esque scenes bring in the first half hour. Needless to say, it’s a shame that the film’s directorial hand comes off as somewhat flat as it holds hands with a strong script.

The night Bernstein meets his future wife for the first time, she tells him, “If summer doesn’t sing in you, then you can’t make music.” It’s a sentiment the musician holds close to his mind and heart as he repeats it to a few filmmakers, seemingly profiling him in the movie’s opening scene—but it isn’t one he thinks about. In the film’s final minutes, we meet again with an elderly Bernstein years after his wife’s passing. He’s teaching a conducting class to college students, including a bright young gay man with whom the maestro works to perfect a section of his composition. But seconds after they iron out the kinks, they’re holding each other close on a sweaty, smoky dance floor of their own making, repurposing the orchestral hall into their own nightclub party. Their inhibitions are ignited by the bright red lights around them, the drinks in their hands, and the flirtatious laughter they share. If for nothing else, Bradley Cooper’s Maestro stays true to Montealegre’s loving words. Summer was always singing inside him, and that fire was the foundation of a beautiful career we will remember for as long as human art is remembered. But further still, it was the foundation for a beautiful life, one that afforded Bernstein many lovers, friends, collaborators, and successes—if only we got a fuller picture of it.