Discovering the Self Through Song in ‘Hedwig and the Angry Inch’

John Cameron Mitchell’s pop-punk masterpiece uses conventions of the movie musical to deliver something beyond words.

This article is part of our One Perfect Archive project, a series of deep dives that explore the filmmaking craft behind some of our favorite shots. In this installment, he look at how song acts as a vessel for self-discovery in Hedwig and the Angry Inch.

In John Cameron Mitchell’s landmark musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch, song is its central character’s window into herself. With powerful beats of deconstructing binaries, understanding yourself on your own terms, and searching for the love that makes us feel whole again, Mitchell’s tale of the “internationally ignored” punk diva – a character he created and performed starting in the 1990s – still resonates after nearly 20 years; the film adaptation has since retained cult status, and now lives on in a restored Criterion release.

Really, to discuss Hedwig is to discuss what makes a great movie musical, considering that it is one. With its array of surreal pop-punk musical numbers, co-written by Stephen Trask, the film’s songs and visuals combine into something wholly unique and exciting: an expression of Mitchell’s particular artistic vision that transcends language itself.

Movie musicals are founded on the idea of spotlighting characters who have something so overpowering to say that, hell or high water, they just have to sing about it. In these situations, music is the only thing that can come close to expressing the otherwise inexpressible; as our own Matthew Monagle writes, singing is an “unfiltered expression of [a character’s] inner monologue,” giving way to some of their most genuine moments on screen.

Hedwig’s musical numbers certainly deliver on that level, considering that they give voice to a such a singular character who has so much to say through her music. Borne from Mitchell’s own thoughts about sexuality and love before the words to express those ideas became more commonplace, Hedwig comes to understand her own layered identity through a series of original power ballads and headbangers; from “Wig in a Box” to “Midnight Radio,” these sequences act as signposts on her quest for achieving fulfillment as a genderqueer artist, and as a person living in a divided world.

These feelings especially come to the forefront in “Origin of Love,” the film’s core ballad. Based on a myth from Plato’s Symposium, the song tells its own origin story of humanity, professing our beginnings as four-legged creatures with two faces until we were split right down the middle by a higher power. To Mitchell, love is something that people inherently desire in order to feel complete, and so we spend the rest of our lives trying to find our missing half; the song that expresses those ideas is one that he says he’ll “keep singing till I croak.”

“Origin of Love” is thus the film’s most personal song and is just as informed by Hedwig’s own history and desires. Growing up as a “slip of a girlyboy” in East Berlin, a botched sex change operation left her similarly caught between poles, lost between the idea of single and lover, man and woman, East and West, bridge and wall (Mitchell refers to this idea as “the binarchy”). Indeed, there’s a vulnerability to her singing about those dualities directly to the viewer, looking right into the camera and telling us how she understands her pain through her idea of creation. How can you search for your missing half if you exist outside of the binary?

The pain down in your soul was the same

as the one down in mine.

That’s the pain

that cuts a straight line down through the heart.

We call it love.

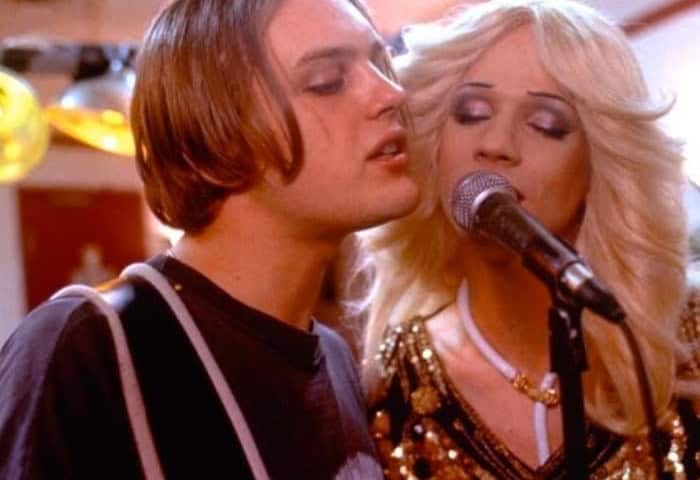

On the surface, it’s easy to view this film as an adaptation ripped from the stage; many numbers see Hedwig and her band on makeshift platforms in Backwater Inn chain restaurants, following her ex-lover Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt) as he tours the US with her stolen songs. But Hedwig‘s musical sequences also never fall into the trap of standard concert-movie fare. Here, Mitchell still creates moments that feel distinctly cinematic, using the likes of split screens, 360-degree camera rotations, animatics, and even a follow-the-bouncing-ball-style singalong to help his character’s songs feel all the more alive.

A set of recurring animation sequences from Emily Hubley especially add that pure cinema power to Hedwig’s personal expressions. Most importantly, they come to visualize the ideas that Hedwig sings about in “Origin of Love.” As a series of evolving creatures scuttle about the screen, morphing into one another in abstract shapes and combinations, they breathe life into Hedwig’s lyrics in a way that only film can show us. Really, while the stage carries its own kind of power, it’s the moving image that makes these “lonely two-legged creatures” manifest before our eyes.

The mirroring of Hedwig’s music and the animatics around her, in turn, brings us to an emotional understanding of her journey. In fact, we see this journey take place right on Hedwig’s body. A tattoo on her hip matches Hubley’s drawings, showing two jagged halves of a face separated from one another. It’s a visual tie that emphasizes “Origin of Love” as the heart of the soundtrack and of the character herself.

This visual is later returned to in the film’s ethereal finale. After confronting Tommy in a void-like concert venue, Hedwig delivers one final ballad, stripped of her usual drag persona. Once her song comes to a close, another animatic emerges onscreen, and we witness the tattoo on her hip morphing into a complete face, the two halves finally made whole. “Origin of Love” then reprises one last time as she staggers, naked, through a darkened alley, into the flickering glow of a streetlamp.

The details of this moment can be interpreted in a number of ways, but it all still points to an acceptance of the self, becoming a “beautiful gender of one,” as Mitchell often states. The scene embraces ambiguity while still delivering an emotional truth, merging the visual and the musical to communicate something without the need for spoken words; somehow, we know that Hedwig has triumphed in her quest, and that even when she leaves the glow of that light, she’s found the love that she’s been searching for in herself.

In the end, this combination of movie musical conventions is what makes Hedwig’s story such an emotional and enduring thing to witness. From the personal power of her songs themselves to the distinctive sequences that visualize them, Hedwig’s journey towards self-acceptance is all pure cinema, and magic from wig to boot.