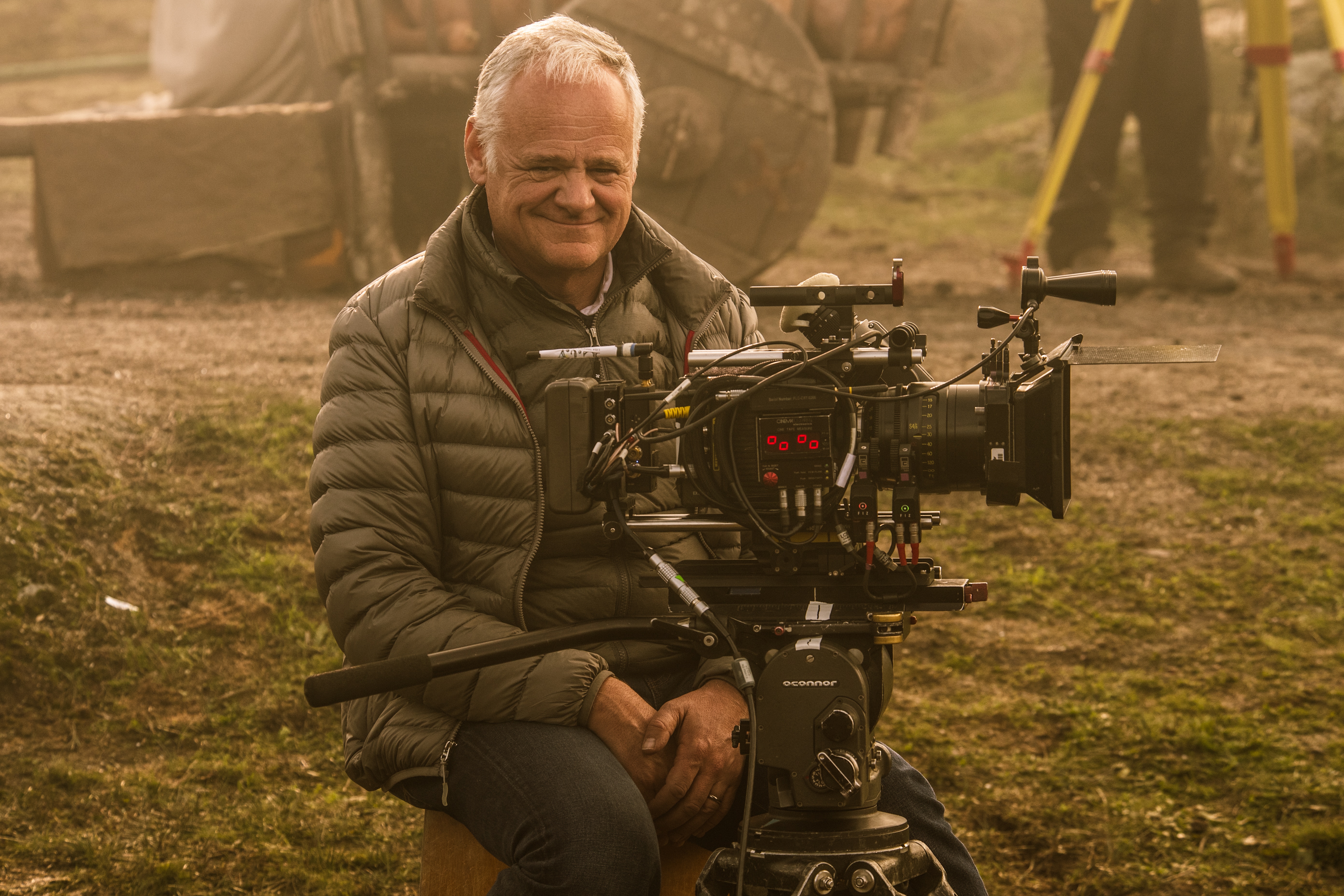

The cinematographer of Game of Thrones, Westworld, and Ray Donovan has photographed some of the biggest TV moments of the decade. It’s time we take notice.

After four decades of work as a cinematographer, Robert McLachlan has found himself in a unique position: choosing between three juggernaut premium cable shows. For the last few years, he has not stopped working, dividing his time between Game of Thrones, Westworld, and Ray Donovan. It would seem like he should hold on to this good luck until it runs out, but that isn’t McLachlan’s style. He is constantly pushing himself, never wanting to become artistically complacent. It’s for that reason he walked away from Game of Thrones and Westworld this year. He’s looking for new creative ground to break.

Catching up with the cinematographer three days after wrapping season five of Ray Donovan, we talked to McLachlan about visual inspirations, the logistics of shooting three shows back to back to back, and the best way to photograph a White Walker.

FSR: You DP shows with some of the biggest fan followings on TV. Do super fans recognize you for your work?

Robert McLachlan: I think industry people are the only ones. Cameramen like to be the guy behind the curtain. We’re not looking for attention. It’s nice when it happens, like at film industry functions, but whenever I do a speaking engagement I’m always amazed at what people find nourishing in terms of information about what I do or how I do it. I really enjoy the exercise because it makes me think about what I actually do, why I do it, and how I do it. After doing it this long and working this consistently, you sort of start to—well, you don’t get in a rut because you’re learning something new every day, but at this point in my career, there are simple ways to do things to achieve a certain effect that aren’t that difficult. I like having to step back and think about the process because when you’re on the floor and under the gun time-wise, you get in the groove, and you’re not that conscious about what’s driving the decision-making as much as the experience.

So it sounds like you work from a place of how something feels. What’s your process from getting the script to shooting the episode?

On Game of Thrones, we have a lot of prep time. The nice thing about it, you have some time upfront, but unlike most TV shows and movies, where all the prep and pre-production is front loaded before you start shooting, the wonderful thing about Game of Thrones’ structure is that usually for a ten-episode season there are five different directors teamed with five different DPs and assistant directors, and the five of you hop between the two full shooting units. But because everybody is there at the same time not everybody can be shooting at the same time. Maybe director A and B will be shooting with the two crews on a given day, and the other three directors will be scouting locations or prepping or bringing the cast in for rehearsals so that we will have an idea of how the blocking is going to be. That gives me time to go work with the lighting crew and get as much lighting done as we possibly can.

Backing up to the script stage, you read the new script—in the case of Ray Donovan and most episodic television, that might be as much as a month in advance, but you really don’t have the final draft until you’re ready to start shooting, or at least prepping. I actually shoot every episode of Ray Donovan. In one case I was directing last season and someone covered for me when I was prepping that—but you read it and I’ll generally have a pretty good idea of the feel and the mood, and what you’re really responding to is the intention of the scene and the writing. The director might have some specific ideas of how he wants to use the camera.

For instance, the first scene that Matt Shakman and I shot for this season of Game of Thrones was with Bran and Little Finger, when Little Finger is giving Bran the knife. We had the location ahead of time, so we went and felt that out and figured out where the best place for Bran to be sitting and the best place to put Little Finger. Directors are usually fairly amenable to blocking in a way to make use of whatever your light source will be—in this case, it was a very small window. Having shot the show quite a bit before, I had a good idea of what lights we were going to need outside the window, what we would have inside, and so on and so forth.

“…this is the first time that Ray Donovan has not dovetailed with Game of Thrones or Westworld. It would have been my preference to not do them anyway…”

How different is your lighting technique between Game of Thrones and Ray Donovan?

In Ray Donovan, LA has been a co-star of the show up until this season, so one of the visual themes of it is the ever-present Southern California sunshine. So for day interiors, I try as much as possible to make it feel as natural as possible but also have that sun as a constant presence. You have a natural justification for artificial lighting in Ray Donovan that you don’t have in Game of Thrones, but in terms of visual tone and mood, I look at it in terms of LA noir versus medieval noir. You’re always trying to build as much texture and beauty into it as you can while being true to the intention of the script.

Game of Thrones, Ray Donovan, and Westworld are all very different genres, but they all contain elements of noir in their look. What is it about noir that gives it the ability to be applied to so many other genres?

Of course it doesn’t apply to something that is more comedic or lighthearted. If you were to impose a look like that to something that didn’t have at its heart a dark story it would start to feel bogus and false, and that’s the last thing you want as a cinematographer. You want the photography to help tell the story as much as possible, but also without anybody noticing what you’re doing. And just the fact that those three shows are basically all I’ve done for the last five years because I’ve been in a unique position. As a freelance photographer, what usually happens is you have to choose between one or the other, but this is the first time that Ray Donovan has not dovetailed with Game of Thrones or Westworld. It would have been my preference to not do them anyway because it would have required me to be away from my family in LA for a long period of time due to Ray Donovan moving to New York next year and the other shows shooting out of town as well. I’m trying to stay close to home.

So you won’t be involved in next season of Westworld or Game of Thrones?

No, they’re already up and running, and I only finished Ray Donovan last Friday in New York. And actually, those two shows are kind of an anomaly for me because I try to only do a couple or three seasons of a show because you see a lot of examples of people who get blocked into a show, and I think you get stale and you start repeating yourself a lot.

As an artist and as a cinematographer it’s easy to become very lazy because you have everything so down pat. Now, that wouldn’t happen with Game of Thrones because it’s so expansive and so far-reaching, and you’re not literally in the same set once a week, every week, for six or twelve months. It’s more like working on a feature where you’re there for a day, or two days at most, and then you’re onto something else, which is what gives it so much visual variety and makes it so compelling to watch.

Whereas a show like Ray Donovan where we’ve got standing sets—we had a boxing gym, which I absolutely adored working in because it was such a beautifully decorated set. It had this wonderful aged patina on it, and it was easy to light. We had that all fully built, and obviously, you try to vary it and never repeat yourself, but being in the same set over and over, it is easy to become lazy.

Quite frankly, I’m not sure if Ray Donovan wasn’t moving to New York, and we’re looking at revamping the entire look of the show, and everything that goes with a change in venue—because we won’t have that ever-present California sun as a theme, for instance, it will be quite different—if it wasn’t moving there next year I’m not sure I would have done it again. My crew is wonderful, but you get a little bored shooting in the same locations again.

Having said that, one thing I like about episodic is that you can experiment, as we have, with sets if you know you’re going to be in them for a couple scenes for every episode. It’s a bit like an actor appearing in a play night after night. They might not nail it one night, but they might hit it out of the park the next night. You’ve got that option to play and evolve, and sculpt the set differently each time you’re in there, and that’s kind of fun. Sometimes it’s just ok, and sometimes it’s really awesome. But just because you really nailed it for one scene—we don’t really default to that the next time we’re in that set because the script’s different, the tone is different, and you have a bunch of new circumstances. So that’s one of the things that keep the creative juices flowing when you are on a series. I think I’ve just finished my fourth season on Ray Donovan, which is a record for me.

“I don’t like doing stuff for the sake of doing it, if it’s not the best way to tell the story.”

So as far as the look goes on Ray Donovan, can you tease anything for the next season?

It’s kind of a blank canvas right now, which is exciting. We just did a week of filming there to wrap season five, and we saw what some of our options were and played with that look a little bit. But New York is a much more difficult place to shoot than Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, we have a pretty good system, and it’s very efficient. You could do several company moves in a day if you have to, and that doesn’t kill you.

In New York, it will be much different. We certainly will not have the huge, beautiful stages that we have at Sony Studios. We’ve got stage 15 there, which is gigantic. It’s actually the same stage that they shot Wizard of Oz. The stairwell in the fight club that goes down into the floor so that it looks like you’re on the second floor, the pit that the stairwell goes down to was originally constructed to lower the Wicked Witch of the West. The history there is amazing.

So we had three big stages there, and we’re not going to have that in New York. We’ll probably be shooting out of a glorified warehouse somewhere. So I think it will probably have a grittier feel. We might get off the dolly a bit and be more fluid and hand-held and make some allowances for the physical limitations of shooting in a big city where you can’t get your equipment really close to where you’re working. I’m really looking forward to it. I’ve got five months to figure out what we’re going to do with it, and I’ll be shooting some tests between then and now. We’ll see. I think it will be fun to breathe some new life into it.

It sounds like you might be returning to your roots of a more documentary film style.

We’ll see. I don’t like doing stuff for the sake of doing it, if it’s not the best way to tell the story. Ray Donovan, up until this point, has had a pretty locked down look. It allows you to compose nice frames, same as Game of Thrones, which is a very classical locked down look. I mean, in our action sequences, only since season five have we been doing a fair bit of handheld, but that’s only in the action sequences. Things like playing with the shutter used to be verboten on that show because they were considered too contemporary and they might draw too much attention. But then it became a necessity when you’re filming zombies because they look a little dippy unless you close the shutter down and give it that nice staccato feel that you get with a 90 or a 45-degree shutter. And we also used it on the loot train attack sequence. We didn’t use it all the time, but we used it quite a bit. It definitely helps.

Again, I hate any kind of cinematography that feels like the cameraman is trying to get you to notice him with like idiosyncratic framing, like framing someone with their head at the bottom of the frame with massive amounts of headroom and stuff, unless there’s a really good reason to do it, unless there’s information up there or some reason other than saying, “Look at me, look at me.” That stuff really puts me off. I’d rather people talk as an after thought about the photography. If they’re thinking about it while they’re watching it then they’re obviously not engaged in the story, and then we’ve failed.

“The scenes that I’m happiest with—and sometimes they’re the simple ones, not necessarily show stoppers—but they were the ones like Rembrandt’s best work or Georges de La Tour’s best work.”

How do you come by the knowledge of how a show is supposed to look? Are you given a lookbook, or a bible of, “Here’s how we shoot this Series?”

I think there was some real evolution there [in Game of Thrones] because if you look back at season one, it kind of looks more like an old-school period studio film. There’s a lot of unmotivated backlight. It’s lit a lot more theatrically. If you look at the day exteriors you’ll notice that they are being lit as well. I think that was coming out of an old-school approach. If you watch season two you see a bit of a transition away from that more theatrical look to something much more natural. I think the cinematographer Kramer Morgenthau found the look that everyone was the happiest with. What they’ve done since then—when I started on season Three and every season after that—they hand each of the cinematographers an iPad, it’s kind of a lookbook. It’s got frame grabs of all the scenes that they were the happiest with over the seasons for each of the sets. So they’re all categorized according to the set or the location, and you can flip through and see what’s been done before. And if somebody did an approach that they really didn’t like you won’t find it in the book.

Another thing that has happened since season three is myself, Jonathan Freeman, Fabian Wagner, and some of the other DPs—we’re all on board with that much more natural look. I call it Enhanced Naturalism. It’s what we’re always aiming for. We will do our very best to make the set look as much as possible like it would really look in real life. So it feels familiar, and there’s no sign of any filmmakers around—and the same thing with a fairly stationary camera.

Something else about the stationary camera, working off of a dolly, what that does as opposed to handheld is that it gives you the opportunity to compose some really beautiful shots. This is a big deal to me because the reason Game of Thrones looks the way it does and is so classically photographed and beautiful has a lot to thank the British camera operators for. They’ve all been at it for a very long time, and they all came from features instead of television. And one of the things I love about working with the Europeans, and particularly the Brits, is their eye and visual tradition is informed by fine art as opposed to movies and television. They’re not framing things just because that’s the way—to give you an extreme example—Gilligan’s Island was framed with the classic Hollywood look.

The first big American show that I did was MacGyver, and that show had a very, very specific locked in old-school rule book on how to frame things. And what I love about the Brits is that they’ve all grown up being dragged through the National Gallery in London. They’ve had access to the great galleries of the world, so their framing in an aesthetic sense is much more informed by the great art starting in the Renaissance up to the 19th century. And that has always been my inspiration in terms of where I set the bar of what I feel like is good lighting. The scenes that I’m happiest with—and sometimes they’re the simple ones, not necessarily show stoppers—but they were the ones like Rembrandt’s best work or Georges de La Tour’s best work.

John Constable “The Hay Wain”A great example—the first scene I did on Game of Thrones was the broken wagon scene where The Hound and Arya encounter the guy with the busted wagon. I said to one of the operators, almost kidding, “I’m going for a John Constable here.” He painted these beautiful landscapes in England in the 1800s, and he took a look at it and said, “Ah, The Hay Wain.” Which is one of his most famous paintings and hangs in the National Gallery. He knew right away what I was getting at, and he set the shot up. I just wish film schools would send their students to fine art. There’s so much you can learn. Leonardo da Vinci used smoke in the background, which I use a lot even in contemporary stuff like Ray Donovan and Westworld because it gives you so much more texture. And you’re not seeing there’s smoke in the room. I use it very, very lightly, and I’ve done it for a long time. I first started doing it on the TV show Millennium back in the mid-90s. It’s a lighting tool, and with HD it’s fantastic because it takes that razor-sharp edge off. If you use it in conjunction with some judicious filtering, I think you can make some much more beautiful images.

You can definitely see de La Tour in the scenes in this season of Game of Thrones in the caves.

In there, supposedly it was pitch black, but I used a little bit of top light. I almost wish I hadn’t in hindsight. There was next to none, if you look at the raw image you would see lots of detail and texture in the blacks, which I do on virtually all my stuff—there’s actually way more in the negative than what ends up. But I like to print everything way down. There’s no way to artificially light that. You’ve got scenes with Dani and Jon walking through narrow, narrow crevasses, and if I tried to light it or enhance it with any kind of artificial light it was just going to look completely bogus and lit. So I just gave Emilia a little lesson on where to hold the torch so that her face was as attractive as possible, and she was lighting both of them. That’s what lit that scene, just like a de La Tour. Actually, until I looked more closely at de La Tour and some of the other painters of his school, I never noticed that the candles they’re holding have four or five wicks, which is exactly what we used. So I guess there really is nothing new under the sun.

Georges de La Tour “St. Joseph the Carpenter”Do you have specific lighting techniques for specific actors like Jack Cardiff, another cinematographer who drew heavily from fine art?

I do. That school in which Jack was working was one where actors would tolerate being told, “Just hold this look right here.” We’ve all seen pictures of old famous movie stars, and they almost only look the way we think they look, for instance, when the camera is well above their eye line, and the light is quite hard but directly over the lens. I’ve had that happen a couple times when I’ve lit older actresses who were famous during that studio era that Jack worked in. Most recently I was working with Ann-Margret on an episode of Ray Donovan, and the interesting thing is until we put the camera right where everybody had always put the camera for Ann you almost wouldn’t have recognized her. As soon as we raised the camera above her eye line and brought the light around so that it was quite flat—and not necessarily totally natural—but when you have someone like that you want to make them look as good as you can. And she looks stunning, but as soon as you move the camera off to the side or in a number of different positions you wouldn’t have immediately recognized her.

And that’s true for many of those actors. Every one of them has a best place to put the camera for them, but in contemporary filmmaking, even on Game of Thrones, it’s about making the environment feel as real as possible and letting the actors move around that environment. Having said that, I’m very conscious of how I light Lena Headey and Emilia because they have to look like a million bucks. The thing is they’re both so gorgeous that if you take a little bit of care with their light and make sure there’s a little something—they both need a white card underneath the frame in their close-ups which opens up the eyes really nicely, and if they’re a bit tired it gets rid of circles around the eyes. But that works for almost any actor.

“…that Malcolm Gladwell theory of putting in your 10,000 hours—that was me 100%.”

What drew you to cinematography?

My dad was a commercial illustrator, and a painter, and an avid photographer and home movie maker. He was a big kid, and he had a lot of hobbies. I grew up in a house full of paintings with a person who made a living drawing and painting stuff, which is kind of enlightening. He grilled into both my brother and I that it didn’t matter what we did when we grew up as long as we loved it. So I used to sneak out of school on Thursdays when the new movies would open downtown. I would usually skip out in the afternoon, and if I timed it right I could catch the bus downtown, see two new movies, and then bum a ride home from my dad from his studio where he worked downtown.

So I loved going to movies, I had access to a darkroom when I was young, and I was taking advanced black and white photography courses at the university by the time I was in high school. I also discovered in 10th grade that we could choose a creative exercise at the end of the year for our final mark. For English class, I made a little film on regular 8 with a soundtrack on a Bolex, and I got an A for it. If I had done an essay I would have slaved over it for weeks and not had any fun, and I would have been lucky if I had gotten a B on it. So I thought, “I’m onto something here.”

Do you have any specific memories of your dad giving you creative advice?

If I saw a movie with him he would respond to it, and he would point out to me if he thought a movie had been well lit or photographed. I remember vividly watching the movie The Hired Hand, which Vilmos Zsigmond shot and Peter Fonda was in. It came out on the heels of Easy Rider. It was a western, but it didn’t look like any western I had ever seen. The same was true of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and soon after that the spaghetti westerns came out, and I would watch those with him. My dad would point out some of the filmmakers’ tricks to me. I remember him pointing out that Lee Van Cleef running through the graveyard was actually just him running in circles and the camera was panning with him. I’ve actually had a hard time talking directors into doing that when you’re on a long lens and you need to feel like you’re tracking with someone but you couldn’t for whatever reason. And it works great—I’ve actually done that a bunch of times. If you pay attention you can learn a lot from that stuff. So he opened my eyes to a lot of that stuff.

Nicholas Roeg’s Walkabout absolutely blew my mind as a young kid going to see it. It made me realize that the camera could be used in amazing ways. I think that, more than anything, when it came time to figure out what I wanted to do for a living I loved movies and I loved photography, so it seemed like a no brainer. The problem was growing up in Vancouver, British Columbia where they made one TV drama called The Beachcombers that was on CBC Television for 19 years. There were no other dramas, and maybe one or two American features would be made there a year. And usually they would bring crews there from Great Britain and sometimes the US, so breaking into that world seemed like a pipedream and an impossibility. The only other kind of filmmaking that was done there were National Film Board of Canada-type documentaries, so I was happy to go be a documentary filmmaker.

“A lot more people ought to reject film school themselves, and just get out and do it.”

There was no indication for the first ten years that I was out of school that there was any possibility that I would work on a big movie or certainly of the scale and renown of a Game of Thrones. I started a little production company and basically starved for the first ten years of getting that company going. I did that to supply myself with stuff to shoot because that’s what I wanted to do. But I kept at it, and that Malcolm Gladwell theory of putting in your 10,000 hours—that was me 100%. I was shooting all this crap. I was shooting commercials for little crummy businesses, with small businessmen who didn’t pay their bills and insisted on being their own spokesman on their pizza commercials. I was doing everything I could as well as the occasional work for Greenpeace with the guy who became my partner, which was a whole other adventure in filmmaking.

We were doing everything we could get our hands on, and finally when I was about 29 I got hired to do a next-to-no budget exploitative feature called Abducted starring Dan Haggerty who is better known as Grizzly Adams. I really thought that I made it. I was making this film, and we were shooting super 16 and we blew it up for theatrical release. And I actually got to go see it in a theater, and that’s when I thought, “Ok, so this can happen, so something bigger and better can happen.” Slowly that became the case. In fact, one of my biggest breaks, I got hired because of Abducted to shoot that adventure show The Beachcombers that I had watched as a little kid. I ended up shooting the last three seasons of it. It was a great learning experience. Here I am, 30 years old, shooting one of the best-known dramas in Canada. And because other people who had worked on it had moved on, I got on MacGyver, which was shooting in Vancouver at the time. I got hired on that, so by the end of its run there I was shooting a couple of episodes as the main unit DP after being the second unit DP for a couple dozen episodes. That all happened because I had put my 10,000 hours in, and when I got a crack at it I didn’t blow it.

My advice to young filmmakers is that’s the best possible thing you can do. You guys are called Film School Rejects, and I really like that. A lot more people ought to reject film school themselves, and just get out and do it. I mean, I went to film school, but the instruction was so lame. It taught me a few things of what not to do, and it exposed me to movies that I had not previously seen. But this was pre-digital and pre-DVD. VHSs were barely invented when I was starting out, so you couldn’t go back and see classic movies like that.

But nowadays with all that out there, I don’t know if you need to do that. I think you need to just get out there and do it. Don’t be too precious about the jobs that you choose to do. I had a wife and two kids when I was very young, and I had to support them, and I was also trying to create a career, so maybe that helped my decisions to not turn down any job. And every single one of them was somebody paying me to actually film something, which was a big accomplishment. You couldn’t go out and practice on your own because a roll of 16mm film, by the time you bought it and processed it, was $100. By today’s standard for ten minutes of recording time that’s a lot of money. So if someone wasn’t footing the bill you couldn’t practice and you couldn’t hone your craft.

I had a couple of friends who were contemporaries who are my age—they could afford to wait for the right artsy independent film to come along that they could really express themselves with and do some beautiful work on because they had the resources. I didn’t have the luxury of being able to pick and choose. I took everything that came along that a lot of other people would have turned their noses up at, but the thing is you’re practicing and you’re doing it, and you’re doing it, and you’re doing it. And I got to the point where, because I wasn’t fussy, I was shooting every day of the week. And the way that ultimately paid off, in the long run, is in an expertise that comes only from experience. The guys that sat there waiting for the right prestige job to come along—they don’t work that much anymore, and they haven’t gotten a lot better over the years either. It’s almost part of the reason I like doing episodic because it keeps you on the floor and you’re learning. There’s no way you don’t get better at what you do when you’re doing it all the time.

“Don’t stay on the same show too long because you’re not going to grow as an artist or a craftsman.”

You’re talking to me right now on my first full week off, other than Christmas and New Year’s, since June 2012. I’ve been on the floor, or prepping, or traveling to a location 50 weeks out of the year for the last five years. Ray Donovan and Game of Thrones’ schedules worked so that I would wrap on a Thursday or Friday and then I’d be on a plane to start the next series of Game of Thrones or whatever it was. You work your whole life to work on a really good quality project, and you’re not going to turn it down. It’s a high-class problem—I consider myself very lucky.

Where does your mentor Richard Leiterman come into the story?

He was a famous Canadian cinematographer who photographed some classic Canadian films in the late 60s and early 70s, most famous of which was Going Down the Road. He was a bigger than life character, and he was very generous. When I finally got into the union and more production started to happen in Vancouver, I got hired as his operator for the remake of Sea Hunt for MGM. Toward the end of the season he was given a couple episodes to direct, and again it was the 10,000-hour thing. Here I was at the end of my first union job, and he said, “Rob should shoot it. He knows how we shoot the show.” So there I was on my first union job, and I was getting a director of photography credit on a big action adventure show.

He had some good advice over the years. I hadn’t seen him in a few years, and I was at the Canadian Society of Cinematographers Awards one year, and he showed up. I had just gotten my third or fourth in a row for episodic cinematography for Millennium on Fox. He gave me a kick in the butt. He said, “Don’t get too comfortable.” He’s the one that put the bug in my ear, like, “Don’t stay on the same show too long because you’re not going to grow as an artist or a craftsman.”

Do you still camera operate?

I do, but I haven’t in a while. It’s not an efficient thing to do especially on an episodic schedule if you want the camera work to be good. You set a shot up as a DP with the director then you have to work out a bunch of dolly moves with the dolly grip. Then you have to refine the shot and rehearse it. If I’m doing that, then I’m not focusing on getting the set lit as well as possible and as quickly as possible. I operate on big action sequences, for instance, when we have an extra camera or if we have an operator get sick. I like doing it, but I prefer not to. It’s just not efficient. If you were on a big feature it would be more feasible, and it is in some ways more satisfying because as good as an operator is or if they know me really well they’re not always going to make the same aesthetic choices in the body of a shot that you do. But I try to get them as involved as possible.

If you could shoot a film based on any style of painting, what would it be?

Andrew Wyeth “Adam”I’d like to photograph a movie that looks like an Andrew Wyeth painting, or a Caravaggio painting. Actually, I do Caravaggio all the time, quite honestly, with Game of Thrones. And even with Ray Donovan, the use of Chiaroscuro is pretty deeply ingrained. One of my favorite artists is J.M.W. Turner, and you’ll see his work showing up in my work quite a bit. A good example is the scene where Jaime comes back to Cersei in the episode “Eastwatch” and delivers the bad news about what happened to the army. That was supposed to be very late in the day, and Turner liked to use a sun source filtered by a heavy atmosphere of smoke or fog. I did that in the battle as well. But going back to the question, I think I’d like to make a movie that looks like an Andrew Wyeth painting.

Related Topics: Game of Thrones