Watching the film, it’s hard not to draw parallels between Star Trek: The Motion Picture and 2001: A Space Odyssey. It honestly feels like Bob Wise was trying out a Kubrickian approach to Gene Roddenberry’s imagination.

Yeah, that’s true.

After the Enterprise leaves dry dock, there is the wormhole sequence. That feels like a visual extension from the Star Gate in 2001. Where do you even begin with something like that?

Yeah, well I didn’t want to do the Star Gate again. I don’t like to repeat myself, and a wormhole kind of makes you think of something other than the Star Gate. Noone, no scientist or astrophysicist knew what a wormhole was at the time. It was just an idea of a distortion in time and space. I came up with the concept of adapting some of the technology of the Star Gate, which was the idea that the camera shutter could remain open for about a minute while we moved a bunch of artwork in front of the camera, and in this case, the artwork we were moving was scanned laser beams on a backlit piece of frosted glass or plastic. I can’t remember the details, but we could create this really strange shape that would morph over time as you moved through it. It was a way to do something that I knew would probably work in the context of the story. Then we had to add all of the streaky time dilation, slow-motion effects to the live-action on the bridge.

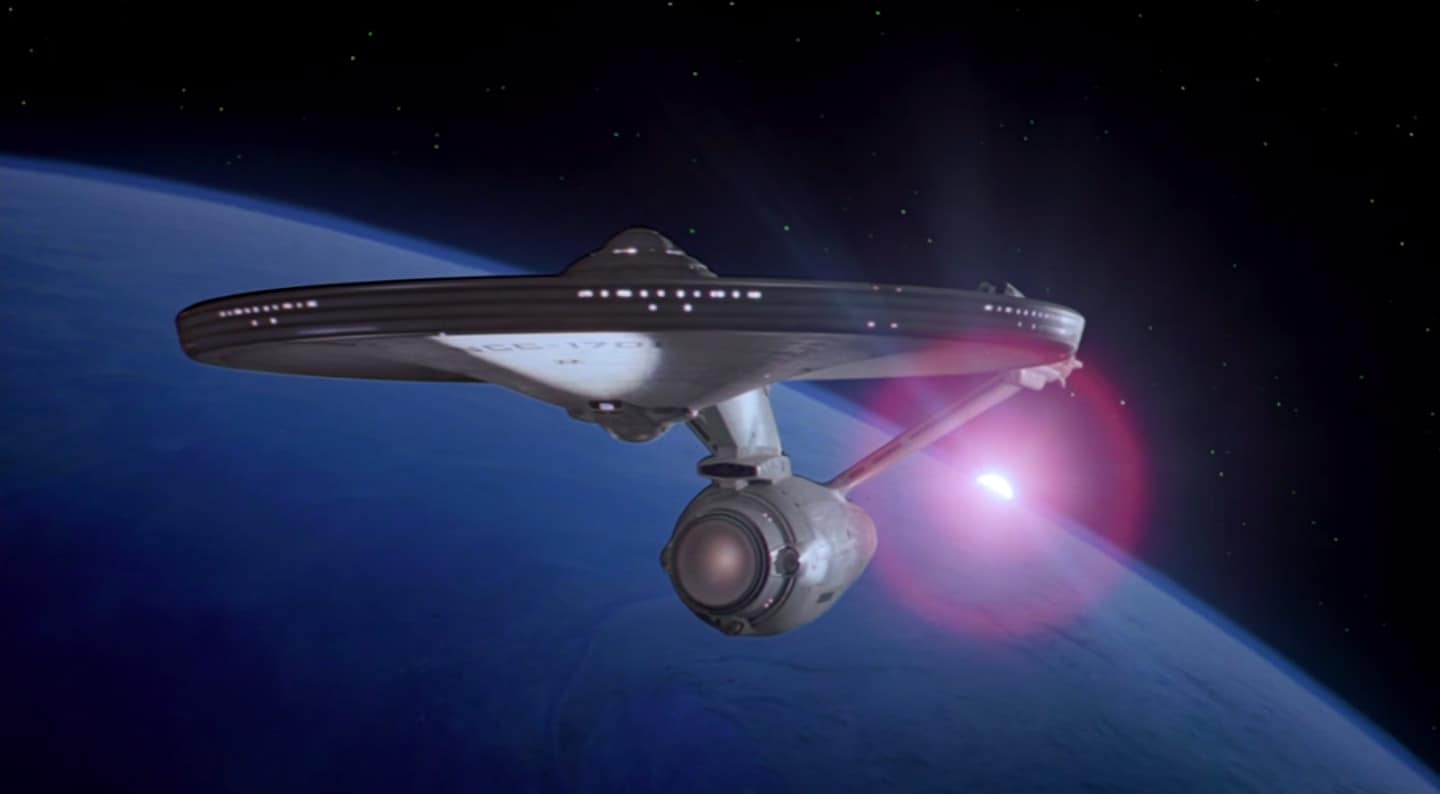

One of the most significant aspects that you contributed to the aesthetic of Star Trek going forward was that you lit the Enterprise from within the ship. If it’s out in space somewhere, it’s still fully lit from within or with a few exterior lamps as well, and there’s a logic to the lighting. How did that idea hit you?

Well, at the very beginning, when I came on board, I saw the Enterprise and I said, “Well okay, they’re going to go into deep space where there’s no sun and no moon, and maybe a few stars, but that’s all. It’s the only source of light. So, why would it be lit? You know, where’s the key light and where’s the fill light?” And everybody looked back at me with blank stares because they never even asked that question. This is the kind of question that I ask all the time, what’s the logic of it? What do you intend to do, and what do you expect it to look like if it’s going to be in interstellar space with no other planets nearby or sun? So, that was my thinking about it. Try to make it space-worthy so that you could see it on film.

In reality, I would imagine that a spacecraft like that would be totally dark and in total darkness, which doesn’t make much of a movie. So, I thought of the way aircraft are lit up. They often have lights on the tail fins that shine. The vertical tail fan is lit up by lights on the horizontal stabilizers and there’s often landing lights on the wings and there’s also lights that light up the fuselage from the wings. You can actually see a commercial airliner at night quite well, and you can actually see lights in the windows. And I thought, “Oh, that’s what we should do. We should light up the inside, put lights in the windows” and we actually had simple lights in most of the windows, but at the stern of the Enterprise, there was a big kind of a cargo door that opened up where you could dock a shuttle and that was detailed inside. It was just all about making it look beautiful and making it look like a beautiful work of art in a way, an illuminated chandelier for lack of a better description. And that was very true for the mothership in Close Encounters.

Yeah, I think you achieved a gorgeous bulb with that one.

Thank you. I think lighting is so pivotally important for everything, and any cinematographer would agree with me. When you’re dealing with something like a spacecraft and deep space, you really have to ask yourself those questions. You know, what’s the justification for the lighting? I just wanted to make the Enterprise really strikingly beautiful on its own because it’s kind of the star of the movie.

When the film came out in ’79, I don’t think people were prepared for that approach on a Star Trek movie.

Right.

How did you feel about the reaction that the film got when it came out?

Well, I was very pleased. I was very pleased to just get the thing done.

Sure. Of course

I was delighted that it was well-received financially and that the Star Trek community of dedicated viewers and fans was pleased with the movie. That was really important to feel like we had taken Star Trek and lifted it to a new level of spectacle. From a small, relatively low budget per episode television series that it was and try to bring it up to scale and make it more spectacular. So, I was really pleased that we pulled it off and that Bob Wise went with it. That’s why they hired Bob Wise, I believe. He had done The Sound of Music and West Side Story and he had a real feeling for epic spectacle on screen. I had worked with Bob on The Andromeda Strain previously, so we already knew each other. He was very happy with my work then. We all got along. I mean it was really everything. Everybody was really smooth and very helpful. Working with William Shatner and the whole team was really delightful.

Related Topics: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner, Close Encounters of the third Kind, Douglas Trumbull, Star Trek