Action heroes, or more accurately the stars who play them, are not often credited as being endowed of great intelligence. In fact, they are more likely relegated to the less distinguished, but no less scientific category of dummy dumb dumbheads. And yet, scratch the surface of the career of each of the biggest, beefheadiest action stars and you will find, in addition to giant foreheads and a shocking dearth of necks, at least one self-aware introspection masquerading as a movie. It would appear that not being able to spell “existential crisis” does not preclude one from suffering one.

These aren’t necessarily brilliant deconstructions, in fact they are usually somewhat clever with plenty of destruction. Regardless, it is an interesting trend to note and often amounts to some very underrated fare from our meta muscleheads. In one specific instance however, an action hero’s meta movie can be so meta as to conceal its true identity as such.

Could it be that the greatest twist Shyamalan ever pulled was convincing the world it didn’t exist? We’ll get to the inarguable meta connection between Unbreakable and Die Hard shortly, but first, to understand this connection, it’s important to identify the inner-directed titles of our most elusive hero’s contemporaries.

Arnold Schwarzenegger playing himself in Last Action Hero

Say what you will about the perfunctory movie references and mugging celebrity cameos, John McTiernan’s Last Action Hero is far smarter than most give it credit. As Jack Slater, Schwarzenegger is playing a caricature of the archetypal Arnie hero. It’s just hard to recognize this because Arnold is, in and of himself, a caricature of a human person. Last Action Hero is the story of an action movie protagonist who is sent reeling through the parallel divide into the real world, and is there faced with the humbling realization that he doesn’t really exist; his life nothing more than a series of contrived plot points.

Heartbreaking, if still starring Schwarzenegger. The meta approach, the dissolution of the fourth wall, and the ensuing identity crisis almost make up for the fact that, in defiance of its own title, the action sequences in Last Action Hero are about as exciting as watching the grass that Governor Schwarzenegger wanted to legalize grow.

Sylvester Stallone playing himself in Demolition Man

Stallone plays a take-no-prisoners maverick cop who accidentally kills a bus full of hostages in his eagerness to arrest what appeared to be Dennis Rodman. As penance, like so many fishsticks before him, he is flash-frozen and thawed out many years later. He is revived in a future in which people subsist on Taco Bell (the only restaurant in existence), listen to radio jingles, and where sex is something at which you can achieve a high score. To that last point, should you do so, please don’t try and leave your initials.

By setting the film in a future that has all but eliminated crime and violence, Stallone’s bruiser cop is assessed as an obsolete relic. Demolition Man is therefore an examination of the cultural value of the action hero as well as a commentary on the lack of tact and dimensionality in the characters Stallone tends to play. It appeared as though Stallone might have had an epiphany here; unlocking a more developed, more layered self-concept that would lead him to accept more challenging projects from that point forward.

He then made Judge Dredd.

Jean-Claude Van Damme playing himself in JCVD

JCVD stars JCVD as JCVD.

As you can guess, that sentence serves as a simplified conceit as well as an early warning for an impending stroke. In this 2008 biographically-influenced drama, The Muscles from Waffles returns to Belgium, seeking to regroup after his career has hit the skids…so this movie takes place in 1996, right? While there, a post office he visits is robbed, and people mistakenly think the falling star is the one behind it. Once again, Jean-Claude Van Damme plays himself here, striking all subtlety from the commentary on his tumultuous relationship with fame and making it almost impossible for him to forget his character’s name.

As goofy as the concept sounds, what with all the jokes and all, JCVD is actually a moving, self-effacing catharsis for an aging action hero dealing with his return to harsh reality. Our high-kicking Kierkegaard even has his own soliloquy in which he lays bare his soul to the camera, to the audience, as we’re all left pondering the same question: “Which one was Double Impact and which one was Double Team?”

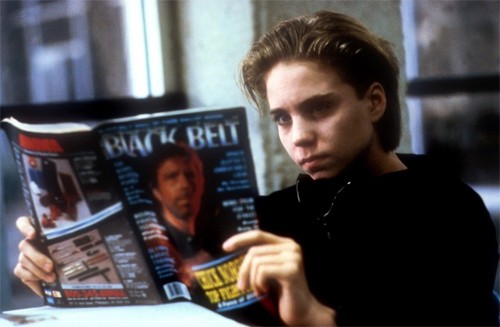

Chuck Norris playing himself in Sidekicks

Heavily maligned, and with no small amount of correctness, 1992’s Sidekicks is the awkwardly touching story of a boy and his bearded, right-wing martial arts hero. Barry Gabrewski – our young hero and not actually the name of your binge-drinking college roomate – is so enamored of Norris’ films that he constantly daydreams about being cast as his, well, you get the idea. Sure, some of the dream sequences may be/totally are dopey, and you may even make the argument that Joe Piscopo is in this movie, but Sidekicks is an interesting acknowledgement and encapsulation of Norris’ body of work.

At the same time, it is a kinetic thesis on the nature of fandom, and how the delineation between actual identity and filmic identity can become fuzzy. How meta is Sidekicks? It’s a movie about seeking the approval of Chuck Norris directed by the obscure younger brother of Chuck Norris.

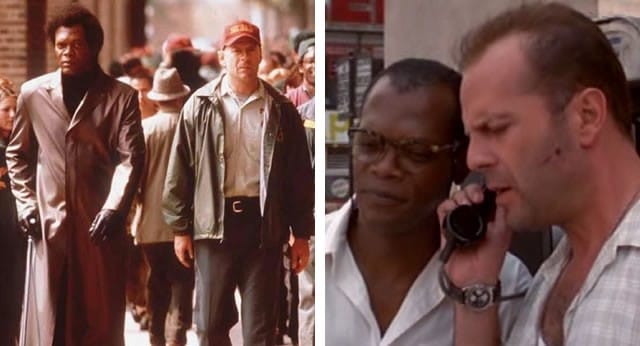

Bruce Willis playing John McClane in Unbreakable

Seen here making a fist with his toes.

This brings us to Bruce Willis. At first glance, Willis would appear to be the outlier. Sure, he has done comedies, but in none of them does he really embody an amalgam of the characters that made him a household name; that is, a regular Joe. The Die Hard model was essentially an ultra-violent affectation of the Hitchcockian hero: the ordinary man in the extraordinary situation. The difference being that McClane’s law enforcement background gave him at least some training in handling criminals, but obviously not on the scale of the terrorists with which he is continually confronted. So where is Bruno’s Demolition Man? Why doesn’t BW have a JCVD? Turns out he does, if you’re willing to look in an unusual place.

It’s M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable.

I can understand your confusion, perhaps even your disdain, but what I’m proposing is merely an alternative interpretation of the events that unfold in Unbreakable. What we have here is a man coming to grips with the possibility that he may be indestructible – an utterly fantastical revelation played with somber realism. What we’re actually watching is John McClane grappling with the fact that, though many a terrorist has tried, he simply cannot be killed. He has been shot, pummeled by henchmen and had his feet slashed by shards of glass, but where a normal man would have perished by Die Harder at best, McClane abides. In Unbreakable however, he abandons his cavalier “here we go again” mentality for something more reflective.

There are little touches throughout Unbreakable that serve as possible hints at a McClane connection. It begins with a train ride in which a married Willis tries to chat up an attractive woman, signaling the same troubled marital relationship between John McClane and Holly Gennarao that ran throughout the Die Hard franchise. Also, SPOILER ALERT, let’s look at the various catastrophe’s Mr. Glass orchestrated: a fire in a highrise hotel, a plane crash, and a train derailment. What do these things have in common? They are all the same disasters John McClane survived during the course of the first three Die Hard films. The explosion on the roof of Nakatomi, the plane that crashes directly over his head in Die Hard 2, and the subway derailment in Die Hard with a Vengeance.

There’s also the fact that Mr. Glass is played by Die Hard with a Vengeance co-star Samuel L. Jackson, and that Willis’ character in Unbreakable is a security guard; serving and protecting even in a marginal law enforcement position.

In closing, consider this: Unbreakable was released in 2000, between the third and fourth Die Hard installments. If we continue along the deceptively rational line of logic that Bruce Willis’ character in Unbreakable is a reflection of John McClane, the placement of Shyamalan’s film is all too appropriate. The major difference between the first three Die Hards and Live Free or Die Hard, in fact the chief complaint among detractors, is that McClane is no longer a regular guy. The ludicrousness of the stunt work in Live Free or Die Hard had audiences inquiring, “when did John McClane become a superhero?”

Now we know.

Related Topics: Bruce Willis