I ordinarily abjure “What This Random Movie Says About Our Cultural Moment And What It Means And Why It Matters” type writing because it’s dumb most of the time, not to mention bad arts criticism. Today I’m making an exception because weekly columns don’t write themselves, and because there’s an exception to that custom: movies specifically about a given cultural moment (and what it means and why it matters), especially one that continues to resonate years later. Tim Robbins’ debut film as director, Bob Roberts, fits this bill, being specifically about electoral politics and the looming threat of the authoritarian right.

Robbins directs himself in the lead, a successful conservative folk singer and semi-secret avatar of various nefarious interests, tied up in everything from savings and loan fraud to the Iran-Contra scandal. The film, told through the framing device of a fictional documentary about Roberts, covering the last month of his Senatorial campaign against an aging Democrat played by Gore Vidal (whose lines were largely unscripted and simply Vidal opining as himself), in which the Republican challenger fabricates a sex scandal against his opponent, makes several actual scandals of his own disappear (through increasingly heightened means), and ultimately triumphs. The film concludes with a plaintive shot of the fictional documentarian (Brian Murray) contemplating the Jefferson Memorial and the inscription, “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

Bob Roberts was filmed approximately a year before the end of the (first) Bush administration, which immediately followed eight years of Reagan, and captures very accurately the kind of fatigued despair that pervaded among progressives at the time. The presentation of the Vidal character, at once possessed of great principle and powerless to stop opaque, cultish button-pushers like Roberts, is a fairly accurate summary of the seemingly over-matched Democratic party of the late 80s.

Zooming even further in, Bob Roberts was made at a point when Bush’s popularity from the brief, noisy flex that was the Gulf War was high enough that his re-election seemed inevitable, deepening the defeatism of the film’s tone. Watching the film now, after the extraordinarily prolonged period in which Saddam Hussein loomed over the American popular consciousness, and the disastrous aftermath of his deposition by Bush II, the way in which Roberts evokes Hussein has been lent a sinister aftertaste.

Many other aspects of the film remain queasily relevant: the fervency of Bob Roberts’ fans. The way in which politics and fandom become blurred. The primacy of extremely shady and crooked money in rightist politics. The vapid acquiescence of the allegedly ultraliberal institutions of journalism and entertainment to celebrity, regardless of politics or even morality. And, most of all, the seemingly unobstructed path to the highest reaches of power afforded to glib, flattering liars.

At its release, Bob Roberts seemed considerably funnier than it does now. I distinctly remember watching it repeatedly in the 90s and chuckling at things, mostly in the first two-thirds of the movie, that felt, at that time, heightened. Rewatching it now, it’s not funny anymore. At one point a young Bob Roberts acolyte played by Jack Black in his film debut says, approving, of Roberts “He believes in America. He believes in making money. Being rich. He’s not one of those sensitive liberals who makes you feel responsible for everything that’s gone wrong.” Fast forward a quarter century and those words could easily be applied to Donald Trump. The only reason there’s a scintilla of hope in 2016 is that Trump may ultimately prove too uncouth and disorganized to attain and maintain a level of support necessary to win. He is the endpoint of the American right trajectory that began with Nixon’s phoenix-like second act in 1968. But Trumps appeal, and the appeal of previous authoritarian rightists from Nixon (and Bob Roberts) onward, is the same. It’s not your fault things are bad. You’re all, as Jack London once put it, temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

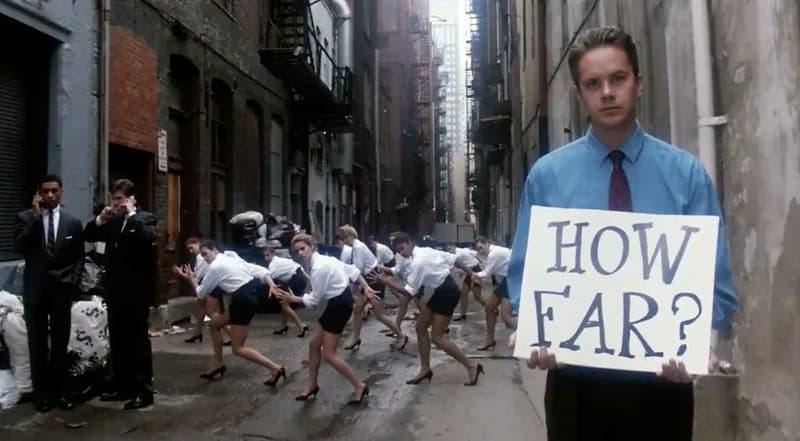

This certainly constitutes burying the lede, being that I’m a film critic, but as a film Bob Roberts stands on its own beyond its continued relevance and the historicity of its political sermonizing. Robbins works in a mockumentary mode that seems restrained to the point of austerity in the age of sensory overload reality TV filmmaking, tipping his hat openly to D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back as well as This is Spinal Tap, as well as the zooms and overlapping audio near-trademarked by Robert Altman (with whom Robbins had worked on The Player immediately before starting work on Bob Roberts).

The supporting cast is a rogue’s gallery of Robbins’ friends – many insisted on playing newscasters – and top-notch character actors (Ray Wise, among the least famous, stood out the most this time because Ray Wise is gold; playing an evil political candidate’s publicist allows him to deploy a truly divine smarm). The handheld camerawork occasionally violates the “mockumentary” conceit, but usually in the service of making the movie better, which is well within civilized bounds. The songs, in the grand tradition of Ishtar, are deliberately bad, but less funny now because, well . . . reality eventually outpaced their absurdity. In short, Bob Roberts is an enviable debut for a filmmaker. It’s a little too impressed with its own political insights, and its fatalism teeters on the brink of being a cop-out, but it’s still a solid piece of cinema. It’ll be a relief when its subject matter is actually a thing of the past.

Related Topics: Comedy, Politics