What Can Old Headlines Teach Us About the Good (and Bad) of Reshoots?

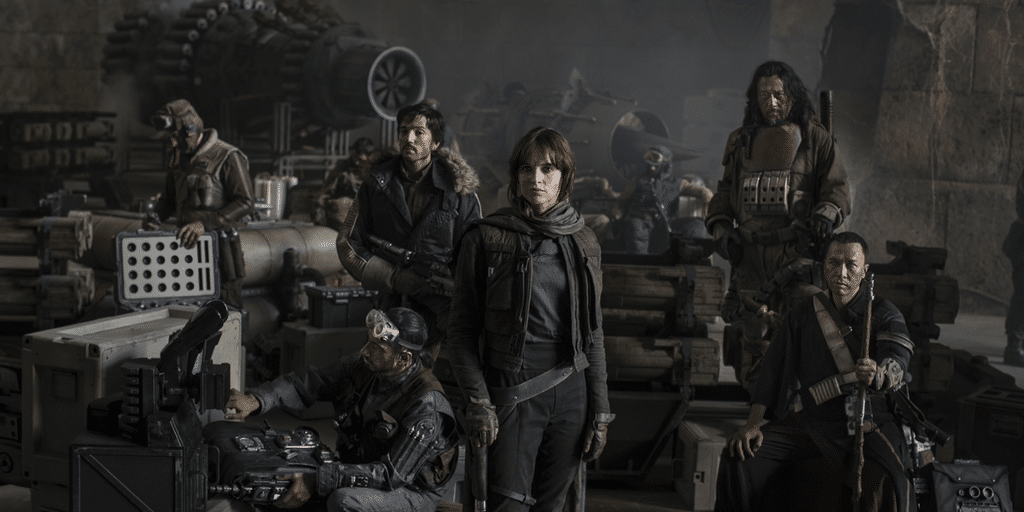

Star Wars: Rogue One went back for reshoots and now everyone is panicking. What a perfect jumping off point for an article, don’t you think?

I’ve already made my feelings on the Rogue One reshoots pretty well known, so never fear, dear reader, our conversation about Star Wars films stops there. What we can do is talk about reshoots. One of the big sentiments to circulate on social media last week was the idea that entertainment writers shouldn’t speculate on an industry practice they don’t really understand. That leaves us those of us without a production background at a bit of disadvantage. It can be surprisingly tough to find historical cases of reshoots that weren’t connected to difficult productions; when a shoot is going well, the minor tweaks that occur after-the-fact rarely make trade headlines. It is only when reshoots portend some kind of box office disaster that they find their way onto the front page of the entertainment section.

With that in mind, I wanted to go digging for a very specific criteria of reshoots. What are the examples from the last few decades of reshoots that made it into headlines but weren’t just a knee-jerk response to test screenings? It was my hope that this would shed some light on the full breadth of reasons why a studio might send a movie back into the oven. Not every film listed below may be considered a modern classic, but they do offer some valuable lessons on why reshoots aren’t always a bad idea.

Oh, and one last note before we get started. It’s not hard to imagine each of the cases listed below as nothing more than revisionist history or public relations; rather than admit their part in a troubled production, these filmmakers tried to pass expensive reshoots off as a natural part of their creative process. True or not, this shouldn’t take away from the underlying logic. Reshoots aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution to film post-production.

Changing the Running Time Changes the Film

The Problem: Sometimes it can be necessary to rework sections of your film to accommodate a shorter runtime. In 1997, The Jackal director Michael Caton-Jones brought actors Richard Gere and Bruce Willis back to Montreal for a series of late-production reshoots. When rumors began circulating that the production was in big trouble, Caton-Jones addressed the Montreal reshoots with the Ontario-based Hamilton Spectator. “The film had a running time of two hours and 45 minutes and I needed to get it down to two hours,” Caton-Jones explained. “That meant taking a fairly sizeable chunk out of it, and when you do that you find by necessity you have to compress the plot.” Rather than recut the existing material and risk losing cohesion, the director decided to use reshoots to condense pre-existing material, in one case turning “eight scenes into a single scene.”

The Lesson: The act of cutting together a feature-length film can reveal some problems in continuity and cohesion. If you put together a rough cut and need to cut your movie down, sometimes a reshoot can allow you to compensate for scenes and pieces of dialogue that would otherwise be cut.

The Editing Process Reveals New Problems

The Problem: Even when the length of a film doesn’t need to be drastically altered, the first cut of a film can reveal the need for small additions. The Coen Brothers have been known to reshoot small sections of their films as far back as Blood Simple; a 1987 profile of the brothers in Rolling Stone magazine used the brothers’ decision to stand-in for their actors during reshoots as a testament to their DIY tenacity. When Variety reported that reshoots for The Hudsucker Proxy were a sign that the project was close to falling apart, Joel Coen was forced to defend their habit of small reshoots. “They weren’t reshoots. They were a little bit of additional footage,” Coen explained. “It was the product of something we discovered editing the movie, not previewing it.”

The Lesson: No matter how much confidence you may have in your script, storyboard, and dailies, you will never truly know what type of film you have until you begin to edit everything together. Even filmmakers like the Coen Brothers – who are often praised for the thoroughness of their approach – aren’t above tinkering with an establishing shot if it doesn’t quite match the rest of the tone.

‘Acts of God’ Are a Fact of Life

The Problem: In the days before inexpensive CGI, the only way to get around missing or damaged footage was to start from scratch. In 1981, director Brian De Palma was forced to reshoot a parade sequence in his thriller Blow Out after footage of the original sequence was stolen. According to the New York Times, “two cartons containing uncut negative film of the movie” were stolen from a van in midtown Manhattan. Nancy Allen, the film’s costar and then-wife of Brian De Palma, painted a tragic picture in interviews of the director “walking up and down the street searching through boxes and cans looking for the film.” The article estimated that recreating the parade would cost the studio hundreds of thousands of dollars despite only appearing for two minutes in the film’s final version.

The Lesson: Wait, this is important. I want you to take another moment and picture Brian De Palma wandering the streets of eighties New York City, kicking over boxes and garbage bags in the hope of finding footage missing from an $18 million dollar film. Now that you’ve fully savored the moment, here’s another fact of life: technical problems happen and sometimes the only way to fix it is to grit your teeth and reshoot what you lost.

The Scene Was Never Going to Work

The Problem: As a filmmaker, sometimes it is necessary to shoot the scene on the page to prove to the studio that it doesn’t work. When David Carson was given the script for the 1994 crossover event Star Trek: Generations, he immediately balked at a scene where Captain Kirk was shot in the back. “What was written and what was accepted by the studio and the producers was never acceptable as far as I was concerned,” Carson told the official Star Trek website in 2011. “I fought for that not to happen, but lost the battle.” When audiences responded poorly to Kirk’s inglorious death, Carson was given the money and creative freedom necessary to reshoot a more fitting ending for the Star Trek legend. As Carson noted, “Captain Kirk’s death now meant something.”

The Lesson: Since film criticism spends an inordinate amount of time talking about writer-directors, it’s easy to forget that films often represent multiple viewpoints. Sometimes you have to swallow your pride and shoot the scene the way it was handed to you. If you’re very lucky, you’ll have the opportunity to go back and fix what doesn’t work a little further down the line.

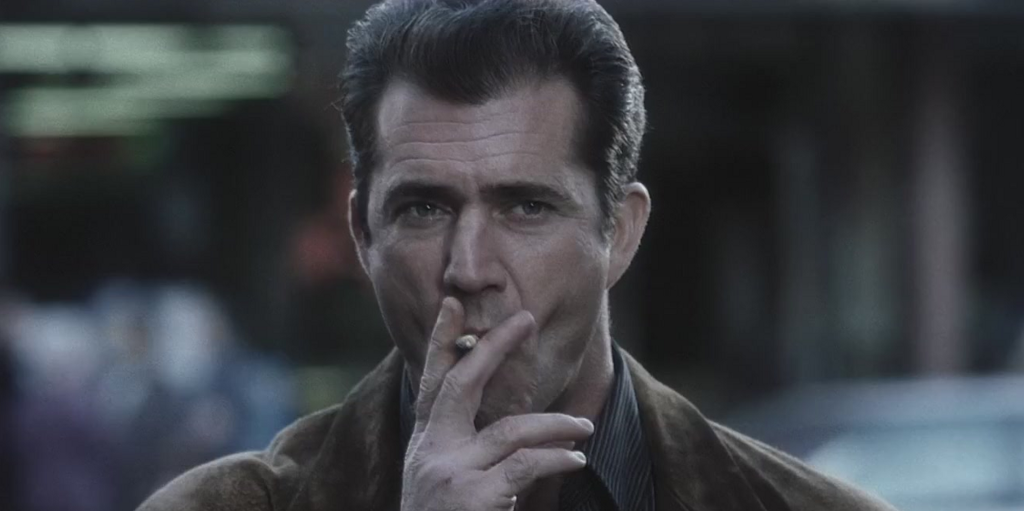

Big Stars Mean Big Problems

The Problem: Sometimes a film doesn’t even make it to a test audience before people start clamoring for changes. According to a January 1999 issue of Premiere magazine, Mel Gibson was so displeased with an early cut of Payback — the directorial debut by Academy Award-winning screenwriter Brian Helgeland – that he immediately requested that Helgeland rewrite and reshoot a full third of the film. When the director refused, Gibson let him go. “As a producer I have to do the best I can for a film,” Gibson told the Vancouver Sun. Gibson would later bring on Mad Max 2 screenwriter Terry Hayes to rework sections of the film and, according to rumors reported by the Vancouver Sun, direct the reworked sections of the film himself with the intent of making his character more heroic.

The Lesson: Years later, Helgeland would have the last laugh courtesy of a director’s cut of Payback released on DVD. According to our own Jack Giroux, Helgeland’s version is the clear winner, serving as a much more “gleeful, tightly paced” movie. Still, Payback serves as a valuable reminder that stars will always have the final say on a project, no matter how many Academy Awards you may have won.

Related Topics: Filmmaking, Hollywood