The story typically goes something like this. In the 1960s, Hollywood had weathered an economic crisis but was losing an ongoing battle with television, so it turned to youth-oriented, smaller projects and gave unprecedented freedom to envelope-pushing directors who worshipped in the churches of Bergman, Kurosawa, Hawkes.

Then Jaws (huge) and Star Wars (way huge) came along in the mid-late 70s, imbuing Hollywood with a renewed focus on entertainment spectacle that has, for the most part, dominated its practice since.

George Lucas’s original Star Wars without a doubt had a significant role in shifting the industrial history of Hollywood toward what we recognize today. It illustrated the lucrative possibilities of mass merchandising, helped elevate B-movie genre fare to A-movie status, and contributed to the now-entrenched thinking that informs our annual movie calendars: the notion that big, expensive fun belongs on our summer movie screens. Yet despite its arguably peerless impact on popular culture in 1977, Star Wars alone resides far more comfortably alongside the film school generation of New Hollywood than the blockbuster mentality it allegedly produced.

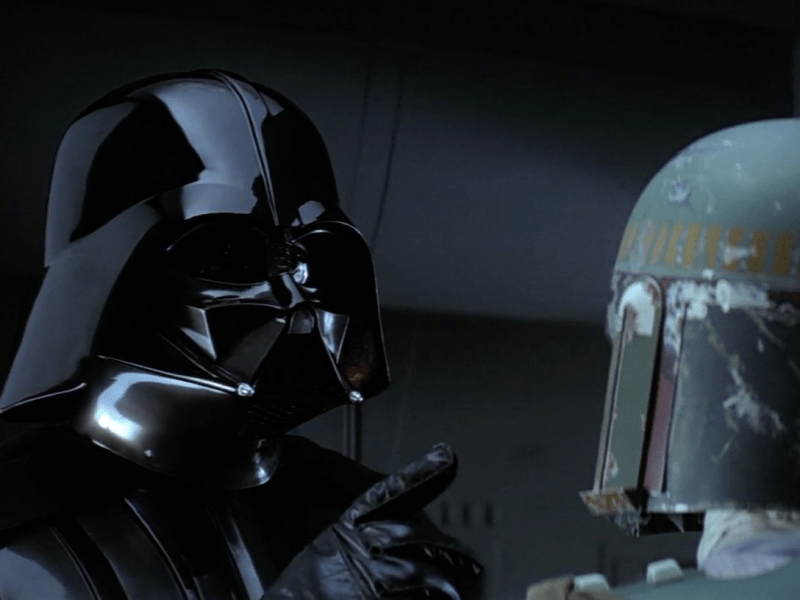

Rather, it was the film’s 1980 sequel The Empire Strikes Back that made good the changes that have since come to dominate the logic of today’s Hollywood.

The Sequel as an Expanding Narrative Universe, Not a Retread

With notable exceptions like The Godfather series (whose first two parts are essentially one complete film), the dominant practice of film series and sequels in Hollywood before 1980 was a simple formula of repetition with slight difference: add a few elements that make a rehash distinct from its original, but promise to reliably deliver the same experience. Take the first two Smokey and The Bandit films, which were also released between 1977 and 1980. Both films have essentially the exact plot skeleton, with the same cast and the same narrative beats, except that the second film co-stars Dom DeLuise while Jackie Gleason stretches into multiple roles.

In the documentary Empire of Dreams, Empire Strikes Back director Irvin Kershner explains the prospect of a Star Wars follow-up within late-70s expectations of what Hollywood sequels could be:

“[Lucas] said, ‘How would you like to do the second Star Wars?’…And I said, ‘Gee George, I don’t think so. It was a phenomenal hit as a picture and a second one could only be a second one. It can’t be as good because the first one is the breakthrough.’”

Kershner was, of course, convinced to helm the sequel, and Lucas laid out the stakes rather starkly. According to Kershner, Lucas explained, “If it doesn’t work, then it’s the end of Star Wars. If it does work, then I can continue making them.”

Lucas’s terms for the future of Star Wars demonstrates the web of determinations between business and narrative in the new blockbuster Hollywood: the extent of narrative storytelling is not dependent upon any perceived need to see a story through to its natural conclusion, but based rather within terms of business success relative to the size of a production; and financial success became, in turn, a mandate to extend narrative. With each entry, the production becomes bigger, as does the benchmark for justifying a continued narrative. These are the seeds of a Hollywood that would become known for skyrocketing budgets and repeated acts of hinging a studio’s worth on the continued relevance of a few familiar properties.

Furthermore, Empire was not, and could never be, a standalone film. It existed within the matrix of a greater narrative universe, an authoritative but not autonomous node in a franchise far bigger than one film (or even three). Empire was released within the context of comic books, speculation, and, of course, a very popular first film.

Perhaps what is most forgotten about Empire is how much it reshaped and altered the way Star Wars itself is viewed. No longer can the original Star Wars be retrospectively understood as the isolated cultural phenomenon it was in 1977; now, it is the inaugurating text in a vast saga that spans across novels, TV series, video games, and Internet ephemera. The “Episode IV ‐ A New Hope” title was not added to the opening crawl until Star Wars’s theatrical re-release in 1981. Up until then, Star Wars was the title of an individual film, not an infinite series. The expanded universe of the present is continually mapped onto the franchise’s past.

Empire changed the way we view blockbuster entertainment and sequels specifically: not as autonomous films, nor even as retreads, but as contributions to an expanding and potentially limitless narrative universe whose existence is justified as long as it remains profitable. The extensive Marvel cinematic universe would be unimaginable without Empire.

A Medium of Franchises (Not Directors) and Entries (Not Movies)

…And people certainly took notice of this sea change in storytelling in the wake of event filmmaking. Vincent Canby’s 1980 review of Empire is a fascinating historical artifact in its honest befuddlement with how to evaluate a decidedly “incomplete” film such as this:

“’The Empire Strikes Back’ is not a truly terrible movie. It’s a nice movie… Strictly speaking, ‘The Empire Strikes Back’ isn’t even a complete narrative. It has no beginning or end, being simply another chapter in a serial that appears to be continuing not onward and upward but sideways. How, then, to review it?

. . . I’m also puzzled by the praise that some of my colleagues have heaped on the work of Irvin Kershner, whom Lucas, who directed ‘Star Wars’ and who is the executive producer of this one, hired to direct ‘The Empire Strikes Back.’ Perhaps my colleagues have information denied to those of us who have to judge the movie by what is on the screen. . . Who, exactly, did what in this movie? I cannot tell, and even a certain knowledge of Kershner’s past work (‘Eyes of Laura Mars,’ ‘The Return of a Man Called Horse,’ ‘Loving’) gives me no hints about the extent of his contributions to this movie. ‘The Empire Strikes Back’ is about as personal as a Christmas card from a bank. I assume that Lucas supervised the entire production and made the major decisions or, at least, approved of them. It looks like a movie that was directed at a distance.”

Even in 1980, Hollywood was still the place of directorial power. In 1979 and 1980, Scorsese, Coppola, Friedkin, and Cimino (for better or worse) could still entice a Hollywood studio towards banking their uncompromising vision. Movies, especially for the cinephile, were in turn readable as the work of a director. The more populist films of Lucas and Spielberg were no different in this regard ‐ they came of the same left-leaning, cinephilia-infused film school generation as Scorsese and Coppola (Lucas was arguably more radical than all of them), but simply preferred a different kind of feature film.

Regardless of what you think of Canby’s review, the shift he witnesses here is quite astute and prescient.

Rather than a film readable through the work of its director, Empire was a film only readable as an entry into a franchise. Lucas’ authorial stamp exists as businessman, showrunner, and spectacle-wrangler, not as the artistic eyes into the narrative universe, evident in stylistic and thematic choices onscreen. What Canby evaluates is the fact that Empire’s personality and style belong not to any individual, but to a narrative system imbued by a set of business interests greater than the person ostensibly calling the shots on set.

In at least technical terms, Kershner’s direction is on point, arguably even “better” than Lucas’s. But while Kershner was a talented director, nobody would argue that it’s his film. And it would be reductive to suggest that it’s Lucas’ film in classic authorial terms. Instead, Empire is a major cog in a far larger assembly line of Star Wars-related narrative contributions, one that evinces the ways that a series can both drastically change tone and expand its scope.

The director is by no means invisible in the franchise film, but it is rarely “their film.”

The Blockbuster Opening Weekend and Its Byproducts

Despite photographic histories that show massive crowds outside major movie palaces, supposedly operating as evidence of the immediacy of Star Wars’s cultural takeover, the original film was something of a grassroots hit. When 20th Century Fox provided little more than posters in support of the film, marketing director Charles Lippincott took to venues like Comic-Con and licensed media outlets like Marvel Comics and Del Rey Books to promote it.

While Lippincott’s efforts are arguably an early precedent for the fan marketing strategies that have since dominated the promotion of fantastic genre films big and small, such practices more closely resemble the niche marketing concurrently en vogue in television’s developments during the late 1970s: most notably the targeted ad bundles of the emerging basic cable market and the regional appeal of early subscription cable networks like HBO. The initial promotion of Star Wars hardly resembles the wall-to-wall marketing that characterizes contemporary blockbusters. Opening to a $36,000 per-screen average on 43 screens, Star Wars’ initial success is due largely to word of mouth demand, not studio hype.

The marketing of The Empire Strikes Back, however, was supported by the full efforts of a major studio, complete with an onslaught of trailers, posters, press interviews, production and casting news, international premieres, and even spoilers with no equivalent to the first entry’s prehistory. More importantly, the relationship between the film and its merchandising was reversed: anything from records to toys to pinball machines preceded the film’s release date, functioning not as means of profiting from an existing cinematic phenomenon, but as objects geared toward the promotion of its predictably lucrative continuation.

Merchandise no longer consisted of ancillary Star Wars products but announced a more reciprocal relationship as objectified means of advertising the film itself. This accelerated, expanded approach to promotion operates akin to the widely cast tentpole marketing of today. Between toys and t-shirts, comic books, and cereal boxes, movie merchandising now developed a circular relationship with affiliated films, simultaneously promoting and banking off of the popularity of a franchise that could potentially exist into perpetuity.

Final Thoughts

As the promotional machinery of Hollywood prepares us for a new Star Wars entry by channeling the series’ legacy, it’s useful to remember what that legacy has inherited, and how present nostalgia often colors the ways we think of the past. Star Wars was an unprecedented cultural phenomenon, but it wasn’t an anomaly of 1977 Hollywood. It is Empire, not Star Wars, that we have to credit for the franchise-based blockbuster mentality that dominates Hollywood’s current business practices from release dates to re-imaginings to universe extension.

With Empire, Lucas created something bigger than himself, something so consequential that it ironically even built up gates into Hollywood through which even he could not enter. It’s all too appropriate, then, that an upcoming Star Wars film as part of a prospective franchise relaunch, by a director other than Lucas, both promotes itself according to and benefits from the very set of practices its creator introduced to Hollywood almost 34 years ago.

Related Topics: George Lucas, Star Wars