Seven men, eight films, and a universe made between them. PLUS: a look ahead.

People don’t often discuss the cinematography of the Star Wars saga. The VFX, of course, the elaborate sets both practical and digital, sure, the costumes and creature design, without a doubt, but when it comes to pulling all those elements together, getting them into frame, and establishing the architecture of the universe, there’s just not a lot of conversation.

Well, we’re here to change that with a look at the six (or seven, depending how you count) DPs who have shot Star Wars, from A New Hope right up to this week’s Rogue One. Plus, we take a look at who’s lined up for the three films still in various stages of production, Episodes VIII and IX, and the Untitled Han Solo Project. It’s kind of a saga unto itself, the cinematographical history of Star Wars, and it started a long time ago in a studio far, far away.

Gilbert Taylor: Episode IV: A New Hope

The franchise started off from a very rocky standpoint in regards to cinematography. George Lucas wanted this first film to have a naturalistic, almost documentary feel, so set out to hire Geoffrey Unsworth, who among several other notable projects shot Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which for all the abstractness of its ending strives to be a very realistic depiction of intergalactic travel. Unsworth, however, was already attached to A Bridge Too Far, so Lucas went with Gilbert Taylor, who was hot off Roman Polanski’s Macbeth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy, and Richard Donner’s The Omen, and who Lucas felt could deliver a narrative documentary look, given his work on Dr. Strangelove and A Hard Day’s Night. But the relationship between Lucas and Taylor was strained at best. Firstly, Taylor didn’t go in for the natural look at all, and felt that certain scenes ‐ those on Tatooine especially ‐ required a more artistic approach. He and Lucas would struggle against each other’s aesthetic visions for the entire film, and by most accounts Taylor hated his time on the project, especially filming at Elstree Studios in London, where the sets were “all black and gray, with really no opportunities for lighting at all.” Taylor took so much time trying to remedy this by physically cutting into the sets and installing new lights that producer Gary Kurtz grew concerned the project wouldn’t be finished on time, and attempted to replace Taylor with Harry Waxman (The Wicker Man). However, the camera crew made it crystal clear that if Taylor went, so too did they, so Lucas eventually overrode the decision and stuck with Taylor. Despite the success of the film, though, Taylor would not be back for the next episode.

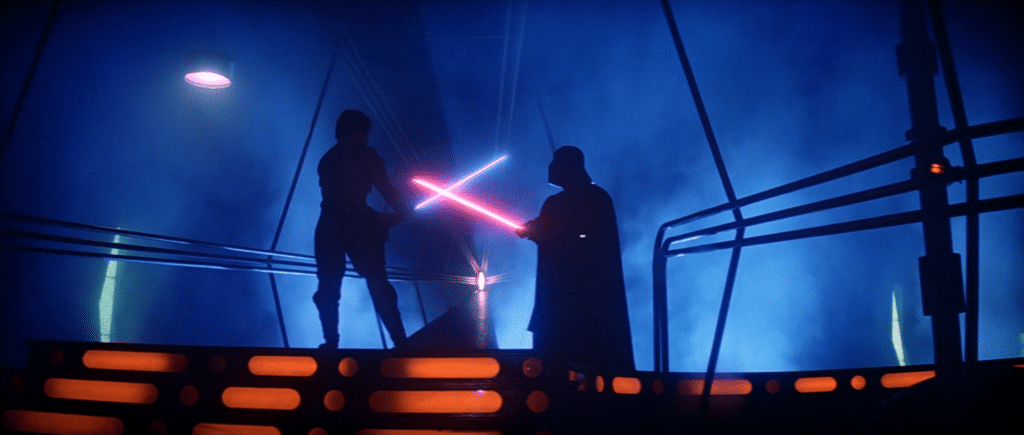

Peter Suschitzky: Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back

With Empire, Lucas stepped out of the director’s chair and passed the baton to Irvin Kershner, who selected as his director of photography Peter Suschitzky, who’d been working as a cinematographer since the early 1960s but whose biggest hits at the time were The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Ken Russell’s Lisztomania. Both are fine films with their cinematographical charms, but neither are the kind of grand spectacle Empire was meant to be. The snowy scenes on Hoth, filmed in Norway, were their own particular hell. The filming corresponded with the worst winter storm the area had seen in half a century, with 18 feet of snow falling and temperatures dropping to below -20 degrees. As you can imagine, this wreaked havoc on the equipment as well as the cast and crew. The scene where Luke escapes from the Wampa cave wasn’t on-set so much as it was Mark Hamill running out the hotel lobby into the real storm while Suschitzky and his crew filmed from the warmer, more hospitable interior. Despite this meteorological hindrance, the rest of shooting went relatively smooth, especially when compared to A New Hope, and especially when compared to Return of the Jedi. Suschitzky didn’t return for that film but went on to have a quite illustrious career, most notably as a collaborator of David Cronenberg’s, for whom he shot pretty much everything between Dead Ringers and Maps to the Stars. Most recently he was the cinematographer on Matteo Garrone’s Tale of Tales, starring Salma Hayek, Vincent Cassel, and John C. Reily.

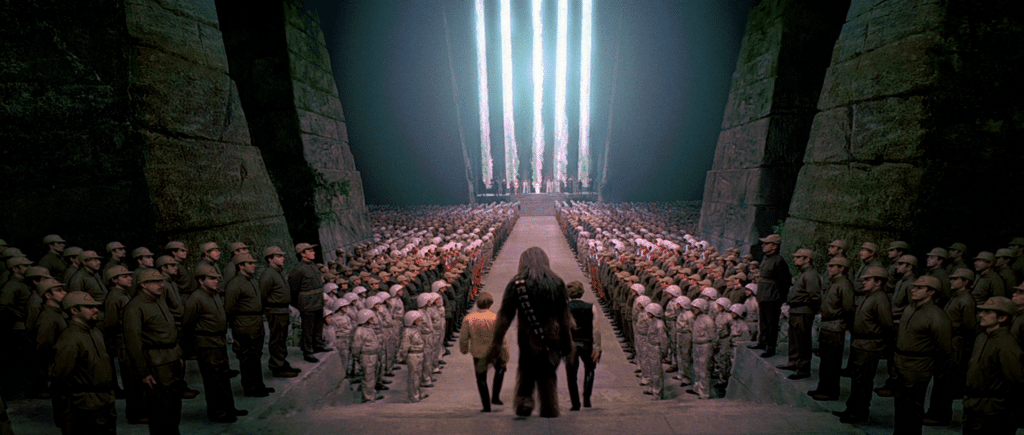

Alan Hume (and Alec Mills, uncredited): Episode VI: Return of the Jedi

As it had begun, the original trilogy went out with major cinematography struggles, this time resulting in a crew member abandoning his post. Lucas looked everywhere for a director for Return of the Jedi, including to old friend Steven Spielberg and other, more eclectic choices like David Lynch and Paul Verhoeven. When all others passed, Lucas settled on Richard Marquand, a relatively-unknown Welsh director who was hired mainly for his ability to bring in a picture on time and on budget, something Empire has most-assuredly not been. With Marquand came cinematographer Alan Hume, who had worked with the director on three projects immediately prior to Jedi: The Legacy, Birth of the Beatles, and Eye of the Needle. Because Marquand was so inexperienced, Lucas was looking over his and Hume’s shoulders every step of the way, to the point Marquand is reported to have quipped of the experience: “It’s like directing King Lear ‐ with Shakespeare in the room.” Eventually this relationship turned sour, with a couple of the actors helping to form the consensus that Marquand and his crew weren’t qualified. When Lucas essentially stepped over Marquand and started directing himself, Hume refused to work with him, citing Lucas’s objectionable treatment of his collaborator and friend. Hume ended up leaving the project before it was complete, which left the rest to be shot by Alec Mills, an operating cameraman. Though uncredited, Mills is largely responsible for the most breathtaking cinematography of the film, if not the original trilogy: the scenes on Endor, including the speeder chase which was staged after production ended and was physically shot on Steadicam by the camera’s creator, Gareth Brown, who walked the path of the speeders shooting at one frame per second, which when projected at 24 frames per second made it appear as though he was travelling at roughly 120 miles per hour, or about as fast as Hume walked away. Post-Jedi (and Octopussy, which he shot the same year), the biggest credit in Hume’s filmography is A Fish Called Wanda, while Mills went on to shoot The Living Daylights, License to Kill, and Lionheart.

David Tattersall: Episode I: The Phantom Menace, Episode II: Attack of the Clones, and Episode III: Revenge of the Sith

Perhaps learning from the past follies of parsing out responsibility, Lucas returned to the director’s chair for all three installments of the second trilogy, keeping at his right hand the same cinematographer, David Tattersall, who had been working with Lucasfilm for about a decade before Episode One as the cinematographer on The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones. Tattersall to that point didn’t have a lot of experience with digital cinematography, certainly not to the extent Lucas was going to use it, and as a result he ended up working very closely on all three films with VFX supervisor John Knoll to make sure what he shot would work with the digital additions to come in post-production. When it came time for Episode III, Lucas went full digital, meaning there was no live-action shooting during principal photography, only sound stage work (though in post some live-action backdrops were photographed to edit in digitally), so Tattersall and team were largely shooting in front of green screens. There were certainly digital-heavy films before Episode One, but no franchise to date had used the burgeoning technology so extensively or in such a groundbreaking manner (The Matrix trilogy started the same year, 1999). It might seem odd or even silly to talk about cinematography in this regard, but the second Star Wars trilogy resulted in a lot of new technology and techniques, so while Tattersall’s cinematography on the films was far from traditional, he did help blaze a trail that many cinematographers have to tread today, and in fact he can be considered one of the godfathers of 21st century cinematography.

Daniel Mindel: Episode VII: The Force Awakens

When it came time to resurrect the saga, director J.J. Abrams wanted to retain the feel of the original trilogy while embracing but not overusing the technology from the second trilogy, which many fans felt took precedent over plot and character development. To help him accomplish this, he went with cinematographer Daniel Mindel, with whom he had collaborated thrice before on Mission: Impossible III, Star Trek, and Star Trek Into Darkness. Though initially the plan was to shoot the film on 65mm IMAX cameras, in keeping to the aesthetic of the original, Abrams and Mindel decided to go old school and shoot on 35mm film, just like the original trilogy had. Not only did this achieve the right look, 35mm cameras are much lighter and quieter than IMAX cameras, as well as being less expensive. There were some scenes that required 65mm ‐ namely the action sequence on Jakku ‐ but they were in the minority. Mindel shot several conscious throwbacks to Episode IV: A New Hope (or just Star Wars). This was another way to reestablish the aesthetic and hopefully the fan fervor of the original films. While some weren’t thrilled by just how closely The Force Awakens mirrored A New Hope, for the most part the visual nostalgia Mindel’s cinematography induced was warmly-received.

Greig Fraser: Rogue One

Now we’re in a slightly speculative realm, because as of press-time, I haven’t seen Rogue One, only the various trailers and TV spots, but the distinction between this film and the others in the canon is clear. Director Gareth Edwards has always said he was approaching Rogue One not so much as a Star Wars film as he was a straight war film. That genre has its own sort of stark, ground-level, frenetic, in-the-shit kind of feel to it, and that was exactly what Edwards was after. Fraser shot with digital Arri Alexa 65 cameras using Ultra Panavision 70 anamorphic lenses, the same lenses DP Robert Richardson used for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight, which allow for very, very wide frames, the kind perfect for capturing the poetic chaos of battle. Ask me in a couple of days how Fraser did.

Steve Yedlin, Episode VIII; Bradford Young, Untitled Han Solo Project; John Schwartzman, Episode IX

As for what comes next, there’s not much we can tell you about the cinematography of future Star Wars films, but we can tell you who’s going to be shooting what. Next on the docket is Episode VIII directed by Rian Johnson, who rumor has taking a page from Abrams’ book and returning to 35mm. Johnson’s cinematographer is Steve Yedlin, who’s shot every Johnson feature to-date. His biggest spectacle picture until now was last year’s San Andreas, which boasted some pretty cool VFX, so expect bombastic things. Episode VIII opens December 15, 2017.

In regards to Phil Miller and Chris Lord’s Untitled Han Solo Project ‐ easily the most-anticipated Star Wars film on the books right now ‐ the directors are enlisting the skills of Bradford Young, who until this year was best-known for his award-worthy work on Ava DuVernay’s Selma. After this year, however, he’s going to be known as (I’m assuming) Academy Award Nominated Cinematographer of Arrival. After seeing Young’s work on that latter film, franchise fans should be extremely excited about what he can bring to the Solo film, which is said to be a spirited and boisterous buddy-action flick. The film hits screens May 25, 2018.

And finally there’s Colin Trevorrow’s Episode IX, which will see John Schwartzman ‐ half-brother of Jason ‐ take over shooting. Schwartzman more so than any other cinematographer on this list is tailor-made for this particular universe: his recommendation letter to USC film school was written by George Lucas after Schwartzman beat him and Francis Ford Coppola (Schwartzman’s uncle) at a game of RISK. So the guy knows conquest strategy, that’s always handy in a Star Wars flick. More important though, he grew up with the figures of this universe in his life, so he’s been around their brand of creativity for a while now. Schwartzman was Trevorrow’s DP on Jurassic World, and has a résumé padded with other FX-driven tentpole films like The Amazing Spider-Man, Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian, Pearl Harbor, Armageddon, and The Rock. Episode IX is scheduled for release on May 24, 2019.

So then there you have it, a rundown of every DP in the Star Wars universe. Some have been more influential than others, some have been more troublesome than others, but all will be remembered for their contributions to the most recognizable and popular film franchise in the world.

Related Topics: Cinematography, One Perfect Shot, Star Wars