This article is part of Tropes Week, in which we’re exploring our favorite tropes from cinema history. Read more here.

The “show within a show” trope is found in works as diverse as Hamlet, The Blues Brothers, and Singin’ in the Rain. It involves the production or performance of a show, play, or movie within a narrative framework. The plot of the internal story often parallels the plot of the external story, so the trope can be used as a vehicle to convey valuable information about the direction of the larger narrative and thereby shape audience expectations.

The trope can be traced back to the legacy of frame stories, a literary structure with origins in global oral storytelling traditions. These narratives are organized so that an outer story “frames” an inner story, nesting one within the other, such as in One Thousand and One Nights and earlier works. This tradition is inherently self-referential, and although the modern form varies greatly from older versions, these roots help explain why this trope remains so prevalent today.

The “show within a show” variation originated with William Shakespeare. Characters performing a play amid the main storyline are used to mirror that plot and predict the outcome of the frame play as well as to parody its emotions and themes. In Hamlet, the play The Murder of Gonzago is performed at Hamlet’s request because it matches the events of his father’s death, and his uncle’s reaction to the performance is key to Hamlet’s decision-making. The show within the show is crucial to the action developing further.

On a more humorous note, the show that’s poorly performed by “the players” at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream — Pyramus and Thisbe — is comedic in its depiction of a tragic romance. The production and rehearsal of the play within the main story is one subplot throughout the entire play, and as it is performed, the characters of A Midsummer Night’s Dream watch and laugh at the performance, matching the tone of the rest of the frame comedy.

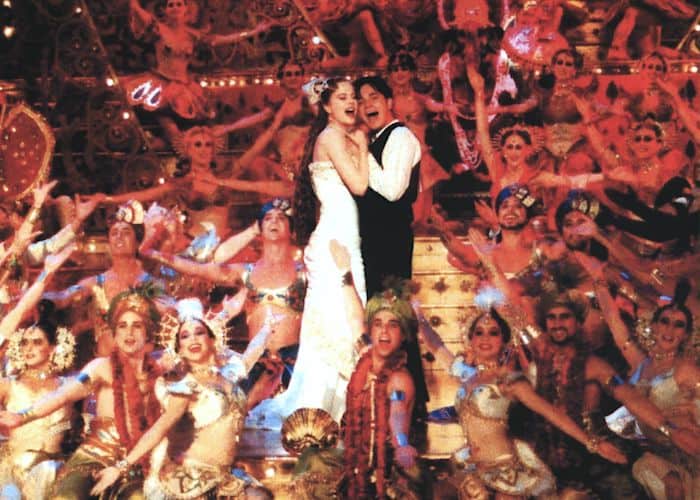

Following in Shakespeare’s steps, this trope was widely adopted by the stage and screen but was especially embraced by musical theatre and movie musicals. In the case of the 2001 film Moulin Rouge!, the production of Spectacular Spectacular by the characters is important to the development of the film’s plot and showcases a doomed love story similar to the one between the two leads.

Similarly, in Singin’ in the Rain, the plot follows stars in Hollywood trying to make a movie at the dawn of sound cinema, with the resulting effort, reworked as a musical and retitled The Dancing Cavalier, thematically telling the story of the main character’s journey (especially in the dream ballet). This informs us of how the plot events of the Singin’ story have shaped the characters, and it emotionally primes the audience for the film’s true finale.

Likewise, the film version of Cabaret uses the musical numbers performed by characters at the Kit Kat Club to reflect on what happens in their lives offstage. Unlike Moulin Rouge! and Singin’ in the Rain, there is a greater separation between performance and the actual events of the narrative, but these numbers are a way for characters to directly tell the audience how they feel about the events of the frame narrative. The performances allow the audience to peer into the characters’ minds and anticipate the narrative highs and lows to come.

The show within a show trope has become so popular and ingrained as a part of musical theatre tradition that it has lead to movies using the trope to satirize theatre and subvert the trope to mess with audience expectations. For example, in The Blues Brothers, the protagonists put on a show to save an orphanage, improbably succeeding with a few bumps and ridiculous car chases along the way, but they still end up going to prison. The movie follows musical logic that putting on a show will save the day while acknowledging how ridiculous it is. They end up subverting the trope, and our expectations, to humorous effect.

A more recent example is found in an episode of the first season of the television show Barry (“Chapter Five: Do Your Job”) when a Shakespeare Showcase is put on by Barry’s acting class. He performs a scene from Macbeth as he is faced with the same moral question that that play deals with. This example simultaneously uses this trope in the classic sense (Barry is just as doomed and trapped as the character Macbeth is in this scene) while also acknowledging it as a very common and obvious trope in theatre.

The meta nature of this trope is what that makes it fun to both follow and to subvert. Because of how self-referential the trope is, the audience can feel the dramatic irony of knowing more than the characters do (such as knowing the lovers are star-crossed in Moulin Rouge!) or can feel their expectations were subverted (as with the ending of The Blues Brothers). Using a show within a show to explain what characters feel and how they have changed is over the top and ridiculous, as Barry demonstrates, but it is effective and entertaining. And, with its ancient roots, it is a modern example of historic storytelling traditions that are still alive and active in media today.