Happy Tex Avery Day! Today, February 22nd, has been declared a local holiday by the animation legend’s hometown of Taylor, Texas (though his birthday is not until Wednesday). He is being honored with a Texas State Historical Marker, and Taylor is celebrating with a screening of his cartoons, guest speakers and a portrait unveiling. It’s a great opportunity to celebrate the legacy of an artist who sometimes seems just a bit under-appreciated next to the likes of Chuck Jones and Walt Disney.

Tex Avery Day hasn’t yet gone nationwide, but it certainly should. He spent many years at Warner Bros. and then at MGM, creating such characters as Droopy, Daffy Duck, Screwy Squirrel and Bugs Bunny. The fact that there isn’t already a national holiday for the guy that brought us Bugs Bunny seems like something of an oversight, right? His work is immensely influential, and some of his cartoons regularly turn up on lists of the greatest animated films of all time. Now, 34 years after his death, is a good a time as any to look back on his finest moments.

The big one is, of course, Red Hot Riding Hood. Its absurd, sexualized fairy tale antics have entertained audiences and excited animators since its debut in 1943. Avery followed it up with a number of his own sequels, and it’s been referenced and parodied more times than you could count. His sultry Red, a jazzy cabaret artist with Jessica Rabbit proportions, would star or cameo in another six shorts. You can get an idea of how this played out with one of the more ridiculous hits, Little Rural Riding Hood (watch it here).

That said, a whole lot has been written about that particular run of hit cartoons. Today we should be celebrating Avery’s whole career, so let’s take a look back at an earlier hit. He was hired in 1935 by Leon Schlesinger at Warner Bros. and given his own unit, which included Jones and Bob Clampett. They worked out of a bungalow at the studio’s backlot, which they nicknamed “Termite Terrace.” Their first film was Gold Diggers of ’49, a Porky Pig comedy about prospecting for gold. The next year they finished I Love to Singa, Avery’s fifth directorial effort at Warners.

On paper, it sounds like a cynical attempt to capitalize on some successful studio songwriting. “I Love to Singa” was written for a feature film of the same year, an Al Jolson/Cab Calloway flick called The Singing Kid. Warner actually did this sort of thing often, commissioning Merrie Melodies to use music that they’d had written for feature-length films. Yet in the case of I Love to Singa, something particularly wonderful came out of it.

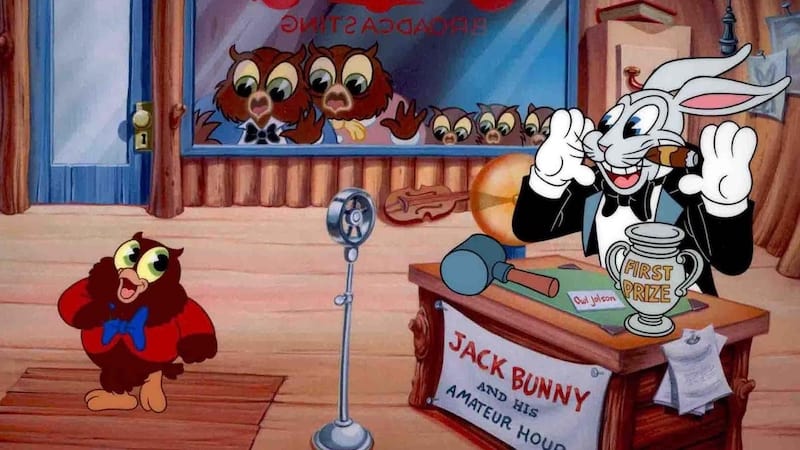

The cartoon begins with couple of happily married German owls waiting for their eggs to hatch. They happen to be stern music lovers, and so they’re overjoyed when their chicks pop out of the shell already dressed for a concert and ready to perform. Yet after three little classical prodigies are born, they get more than they bargained for from the fourth egg. The last of the group is a ready-made jazz singer, a regular Owl Jolson (a joke actually used in the cartoon). The father owl loses it, shrieking about how no son of his will ever be a “crooner.” Things get sillier from there, as the jazzy kid tries to strike out on his own. It’s got the earnest charm of many a 1930s cartoon, with all of the requisite pizzazz.

The real story here, however, is the color. This was one of the first Warner Bros. cartoons to use the three-strip technicolor process, a method which was pioneered and then controlled by Walt Disney back in 1932. The first cartoon to use it was the Oscar-winning Flowers and Trees, after which Disney had an exclusive contract with Technicolor until the end of 1935. When that expired, other studios rushed to use the method in their own films.

I Love to Singa is gorgeous and bright. The giant yellow and green eyes of the owls are striking, drawing attention to Avery’s already quite skillful mastery of exaggerated facial expression. The blues, from the door to the owls’ tree house to the various jackets and bows worn by the characters, are particularly bold. When young Owl Jolson makes his way to amateur hour at the local radio station, the line of contestants in front of him is a vibrant panoply of birds in funny hats. More than just a clever exploitation of a catchy tune, this may very well be Avery’s first masterpiece of the form.