This essay is part of our 2016 Rewind, a look back at the best, worst, and otherwise interesting movies and shows of 2016.

Isabelle Huppert is without a doubt one of the finest actresses of all time, an immense talent we’ve been fortunate enough to witness for decades. She is the most nominated actress for France’s César Award, with thirteen nominations; she has had more films in competition at the Cannes Film Festival than any other actress; she is a BAFTA winner, Silver Berlin Bear Winner and she unanimously won Best Actress at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival for her role as Erika Kohut in Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher. In short, Huppert is who Meryl Streep likely wakes up wanting to be.

As 2016 wraps up and awards season kicks off, Huppert is once again being lauded for her performance in Paul Verhoeven’s provocative and controversial film Elle, a role for which Huppert has already won Best Actress at the Gotham Independent Film Awards, the New York Film Critics Circle Awards and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards, in addition to her Best Actress nominations at the 2017 Golden Globe Awards and the Independent Spirit Awards. It is Huppert’s fearless performance in Elle, as well as her sublime turn in Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come (L’Avenir), that have commanded our attention and have led us to declare Huppert our 2016’s Performer of the Year.

In Things to Come, Huppert shines as Nathalie, a successful philosophy professor whose life begins slowly unraveling, first with the end of her marriage, then with the termination of her long-term publishing contract and finally, with the death of her mother (a terrific Edith Scob). Yet despite each blow, Nathalie remains resolute, finding fulfillment and stimulation in her intellectual career, her children and grandchild, and in the tantalizing but ultimately professional mentorship with her protégé and former student, Fabien (Roman Kolinka). In Huppert’s capable hands, Nathalie never slips into the tired cliche of a woman on the verge of a breakdown. Instead, she imbues Nathalie with a sense of hope, each new challenge is simply part of the unpredictable and bumpy journey that is life.

It is a role that seems tailor-made for Huppert, something which Hansen-Løve confirmed at a press conference following the film’s premiere at the New York Film Festival in October. “Since the very beginning it was obvious for me that if there was one person that I could imagine in that part, that could be Isabelle.” For Hansen-Løve, it was Huppert’s authority and intellect that gave her credibility as a philosophy professor. But beyond this, Things to Come truly excels due to Huppert’s masterful portrayal of a woman who must re-evaluate her life, finding value in things once discarded or unimportant, while also cherishing the memory of things now lost.

It isn’t the first time the pair have worked together; Hansen-Løve played Huppert’s daughter in Olivier Assayas’ Sentimental Destinies (Les Destinées Sentimentales) in 2000, but Huppert has especially high praise for Hansen-Løve’s talents as a director. “She has this amazing intuition, keeping the balance between depth and lightness. I think that’s something that runs all throughout the film, this balance that makes the movie light and deep at the same time, dark and lit up at the same time and she knows exactly how to pull all those threads.” This syncopation between light and dark is evident throughout the film. As Nathalie accepts the dissolution of her marriage, she also becomes a grandmother; although she is told by her publishing company that her textbooks aren’t “sexy” and don’t sell enough, we see in multiple scenes that her students are engaged and invested in her lectures and ideas. Despite her losses, Nathalie is able to find balance.

In one of the film’s crucial scenes, Nathalie reads from Rousseau, explaining to her students that it is possible to find beauty in nature, to find fulfillment in the external and that finding hope in the promise of love, even if it is never realized, can bring happiness. It connects seamlessly to Nathalie’s earlier declaration that she is totally fulfilled by her intellectual life but it also touches on her relationship with Fabien, one driven not only by mutual intellectual admiration but also by an unspoken longing. With subtle glances and unspoken words, Huppert is able to convey Nathalie’s secret inner contradictions, we are able to feel the weight of her desire paired against the tough, always on the go, unflappable exterior she projects to the rest of the world.

The film closes on Christmas, with Nathalie leaving her children behind to pick up and soothe her crying grandchild. As The Fleetwoods version of “Unchained Melody” begins to play we pan out of the bedroom, giving the tender moment its due privacy, leaving us to ponder on the inevitability of time and how the unpredictability of life can still be offset by love. “I think it’s about that paradox and the fact that you can both accept life and its cruelty and irreversibility and at the same time still enjoy it and have hope and wait for something or somebody,” Hansen-Løve said of the film’s final scene. Indeed, as Nathalie shares a sweet moment with her grandchild – Huppert joked about her tender touch with the crying child saying, “I’m very good with babies, they do whatever I want them to do, it’s my thing.” – we feel nothing but hope for her, no matter what comes her way.

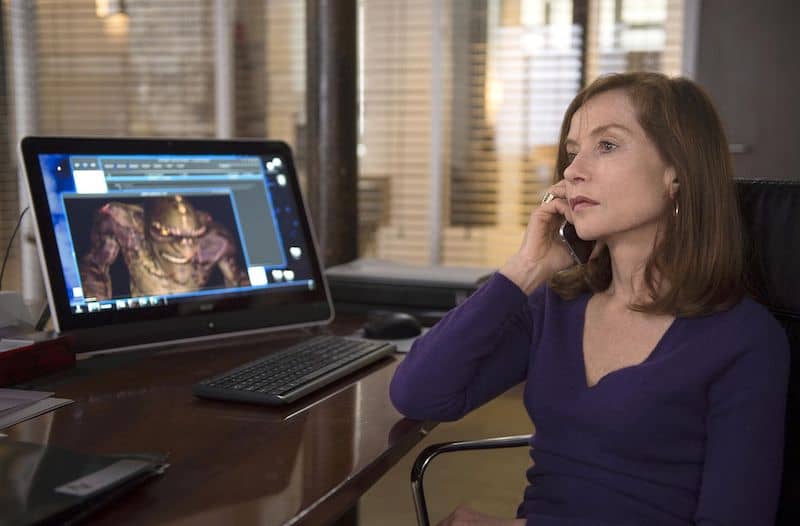

It’s an interesting note to end on considering how seamlessly Huppert’s poignant turn as Nathalie segues into her tour de force performance as Michèle in Verhoeven’s Elle, as both are highly successful women who must press on defiantly in the face of daunting and unexpected personal circumstances. In Elle, Huppert’s Michèle is the successful owner of the video game company who refuses to submit to victimhood after she is brutally raped in her home. Instead, upon learning the identity of her attacker, Michèle begins a playing dangerous cat-and-mouse game in an attempt to strip her rapist of his power through her own sexual gratification.

Speaking at the New York Film Festival in October, Huppert summed up Michèle as “a post-feminist character, building her own behavior and space somewhere between. She doesn’t want to be a victim that’s for sure but she doesn’t even fall into the revenge or avenging character, taking a gun and killing the guy, she’s somewhere else.” Just where Michèle winds up has fueled much of the film’s controversy, as Michèle eventually lures her rapist into a second encounter, one in which she attempts to gain control by finding sexual gratification in the act. But Huppert never flinches from Michèle’s more complicated and contradictory emotions and it is this fearless portrayal that elevates the character from something abstract into a fully-realized and fascinating performance that leaves you spellbound. Huppert roots out our own raw discomfort and defiantly forces us to face it head on, whether we like it or not.

It is worth nothing that Michèle is surrounded by men who have failed in their own lives, as well as in their subsequent relationships with her. Michèle is divorced and more successful than her husband, who is a failed writer; she is carrying on an affair with her best friend’s husband, whose love and obsession she does not return; and her son is stubbornly and blindly raising a child that is not his own. Beyond this, we soon discover that despite her best efforts to cast off her childhood, Michèle’s father is a notorious French serial killer and, due to him sparing her life, many suspected she was compliant in the crimes. In a way, Michèle’s guilt or innocent is irrelevant, to Huppert she is simply the product of men’s failures, “All the male figures are weak and sort of coming off from their pedestal and she’s the product of that new era in a way.”

Beyond Huppert’s powerful performance, the success of Elle stems from its refusal to slot into any one genre; like Michèle, it is a film that defies definition. It is a trait that Huppert feels is prominent in many of Verhoeven’s films. “He doesn’t embrace one genre, there are so many layers in his films that go beyond any explanation and I think it leaves people very much off balance,” she said. “I think that’s maybe what you call provocation but I think that’s creativity and films are made for that, to leave people with more questions than answers and obviously thats what his films do.” With Elle continuing in this tradition, Huppert believes that the flexibility of genre is one of the film’s greater strengths. “You think it’s a thriller and then immediately he pulls you backwards and then takes you somewhere else. It’s not one genre but life is not one genre, you can start out like a comedy and then end up with drama all in the same day, so in a way it approaches the essence of reality.”

It’s still a long road to the 2017 Academy Awards – Elle was left off the Oscar’s shortlist for Best Foreign Film – but Huppert has been nothing short of electric this year, building even higher on a career that reads like a master class on exemplary acting. Her performances in both Elle and Things to Come remind us once again that a truly extraordinary and rare talent such as hers can utilize the challenges that others might find limiting to elevate the craft into a new realm of possibility. Isabelle Huppert is not only our Performer of the Year, but she is a reminder of why we cherish cinema in the first place.

Related Topics: 2016 Rewind, Performer of the Year