The life of a film critic is one of the swankiest and most lucrative jobs you’ll ever have. Forget doctors and lawyers. Forget international business. Forget technology. Film criticism, particularly that which involves publishing on the internet, has me rolling in money like Scrooge McDuck. I’m not just rich, I’m stupid rich.

Still, when it gets to be the middle of the month, and I’m paying bills, I can come up a little short. There never seems to be enough money in my bank account to comfortably live. It’s around this time that I start to think creatively about how to make even more money than my swag-filled, jet-setting life already brings me. Sure, there’s always the possibility of becoming the trophy companion of a supermodel. I certainly have the rippling muscles, two-percent body fat, and inguinal arch of Ryan Gosling. Then again, I’m happily married, and that might be a deal-breaker for a sugar momma.

After recently watching Superman III and Office Space, I realized that the best way to make ends meet might be a life of crime. After all, I live most of my life on computers. Just ask my 2,693 Twitter followers. That’s got to be worth something.

This got me thinking: Could I use the banking glitch we saw in Superman III to get even richer than I am today?

The Answer: Yes, but really only enough for an Amazon gift card.

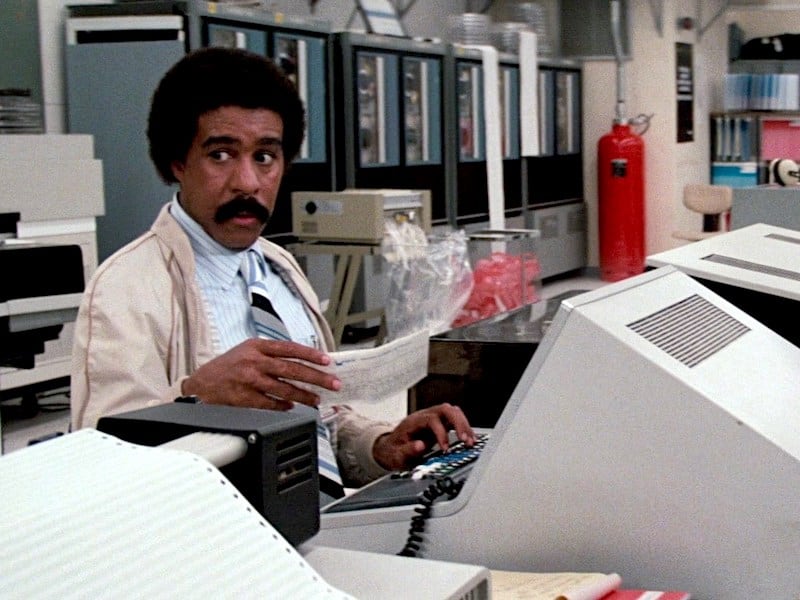

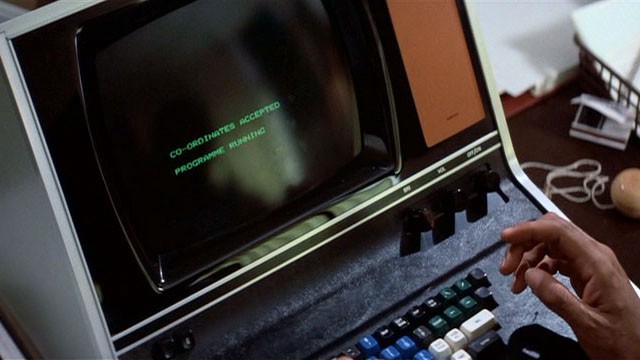

In Superman III, this particular scam takes shape when Gus Gorman (Richard Pryor) receives his first paycheck for $143.80, and a colleague tells him that his paycheck probably includes a half-cent extra due to taxes and other calculations. Because Gus is an inexplicable computer genius, he writes a program for the company’s computer system to gather up all of these fractions of a cent for him, which results as a bonus check for $85,789.90 at the end of the week. Of course, the company’s accountants immediately notice the sudden loss of funds and finger Gus the next day when he nonchalantly drives his new Ferrari to work.

This plot point was later borrowed for Mike Judge’s film Office Space, where the programmers write a virus that essentially does the same thing. Their hope is that their indiscretion would be hidden in the Y2K panic that was happening at the time, but like Gus’s check, it was too large to ignore. Other films like Entrapment, I Love You Phillip Morris, and Hackers feature similar iterations of this plot device.

The general concept of illegally skimming off the top goes back decades, and it is colloquially called “salami slicing” (which sounds way dirtier than it really is). This term alludes to trimming off a bit of salami so small that it goes unnoticed, and the entire salami can then be sold as a whole. In the bigger picture, salami slicing can be used for any practice that involves the use of acquiring small parts of a whole, whether it be border disputes with China or information security gleaned from the equally dirty-sounding “salami attack.”

From a monetary standpoint, the earliest attempts of salami slicing was a process known as or “coin clipping,” in which a person could use a blade to shave off a tiny portion of a silver or gold coin. Do this to enough coins, and you’ll amass a valuable amount of precious metal while leaving the original coins generally intact. Of course, when this is done too much, it will cause the destruction of the coins or worse, contribute to monetary inflation. This is why coins once cast in silver (like the dime or the quarter) were originally minted with ridges on the edges, making only full coins legal tender.

But there are no ridges on digital money, so…

Why hasn’t anyone done this before?

They have, but not exactly the way Gus Gorman does it. While it may take the wind out of your creative sales, the Superman III salami slicing technique is not as widespread as Hollywood would lead us to believe. Though that does not mean it hasn’t been tried.

Variants of salami slicing have occurred throughout the ages, even before modern computer systems were put into effect. Thomas Whiteside’s 1978 book Computer Capers tells of several instances of banking fraud using small amounts from different accounts to make a profit. However, most of the real-life stories of salami slicing involved charging various accounts small amounts rather than gobbling up the fractions of a cent left over from tax and interest calculations.

For example, Michael Largent used a deposit verification loophole in E-Trade and Schwab to siphon off more than $50,000 from the online brokers. Their systems would verify a trade account by depositing between one cent and two dollars into it. By creating 58,000 dummy accounts, Largent was able to accumulate a nice sum before he was caught, tipped off by naming some of his accounts after characters in Office Space.

There are other famous examples. One includes a Taco Bell employee named Willis Robinson who arranged for customers to be charged the full amount for food with only one penny being directed to the company while he pocketed the rest for himself. Another includes several gas station employees being arrested for rigging pumps to overcharge customers. Garment workers in New York once diverted two cents from every paycheck into a tax withholding account, later getting the money back in a return.

One of the highest profile cases in recent years involved offshore trading companies shaving only a few pennies off of accounts of more than a million customers. Even then, the scheme worked for a while simply because the amount was so tiny in the grand scheme of things that only six percent of customers disputed the charges.

So, salami slicing is alive and well, and people will find a way to exploit system resources for profit, but…

What about all those fractions of cents?

They’re still out there because banks and other financial institutions operate to the whole cent. However, there are just as many negative fractions out there as well. Banks and corporations don’t simply truncate the final value, as Gus’s colleague suggests in Superman III. Instead, the numbers are preserved internally to five or six decimal places. Then the value is rounded rather than truncated when a check is cut or a deposit is made. That means that instead of just chopping off those fractions of a cent, they round up or down to the nearest cent.

In other words, it all works out in the end. While some transactions will yield an extra few fractions of a cent, others will yield a few fractions less than a cent. When millions of these calculations are crunched together, statistically speaking, it should all zero out. (Still, that doesn’t stop the IRS from having clearly-defined regulations on what to do with the extra income that results from fractional calculations.)

The reality is that even if you could collect all the positive fractions out there, it would be hard to keep this under the radar. The Superman III scam wouldn’t work on a small money system because there simply aren’t enough accounts to make the final sum worth your time. It would only work in a system so large that the fractions of cents would add up to a hefty sum, and banks and other financial institutions tend to notice tens of thousands of tiny transactions diverting thousands of dollars into dummy accounts.

In fact, seemingly taking a page from the character of Matt Franklin (Topher Grace) in the forgotten 2010 film Take Me Home Tonight, Romanian security researcher Adrian Furtuna built a machine that would exploit the fractions of cents generated in international currency transactions. The machine works by initiating many tiny trades, designed to generate a slight increase in value, usually as small as 0.005 Euros. Furtuna designed the machine to read and respond to security authorization codes that regular computer programs cannot. This cumbersome process limits the number of transactions to just under 15,000 transactions a day, resulting in a profit of about 68 Euros (about $91) every day. (However, most banks’ anti-fraud mechanisms would detect that high number of transactions, making the scam ultimately ineffectual.)

In the end, the Superman III salami slicing simply isn’t feasible or realistic. And that leaves me to finding a sugar momma to keep me in the posh lifestyle to which I’ve become accustomed.

Related Topics: Richard Pryor, Superman