The year that had it all.

Welcome to Debate Week, the first of what we hope to be many weeks in which we open up a topic of a discussion to our entire team. This week: What was the best year in movies, ever? Throughout the week, our team will each make the case for their chosen year. Follow us on Twitter to place your votes on Saturday, April 7.

Like the rest of the Film School Rejects team, I was excited when Neil pitched the “Debate Week” idea. However, unlike many of my colleagues, I did not have an instantaneous response at the ready. Instead, I turned to my trusty Letterboxd account. I automatically disqualified the past five years — it’s too soon to determine significant legacies or develop proper hindsight — and then surveyed what was left.

My conclusion? 1998 was one damn fine year, cinematically speaking. The triumph of Shakespeare in Love at the Oscars is far more a testament to The Weinstein Company’s cutthroat awards campaign strategy at peak effectiveness than an accurate reflection of what 1998 had to offer. I mean, it’s an okay film with pretty costumes, and it manages to make Gwyneth Paltrow likable, which, depending on who you ask, is a significant accomplishment, but still, it’s not exactly revolutionary content. Looking at the box office side of things, the biggest winner of 1998 was Michael Bay’s Armageddon — again, not a promising sign. But, like many treasures, 1998 may not look impressive at first glance, but upon closer inspection, is a veritable jackpot.

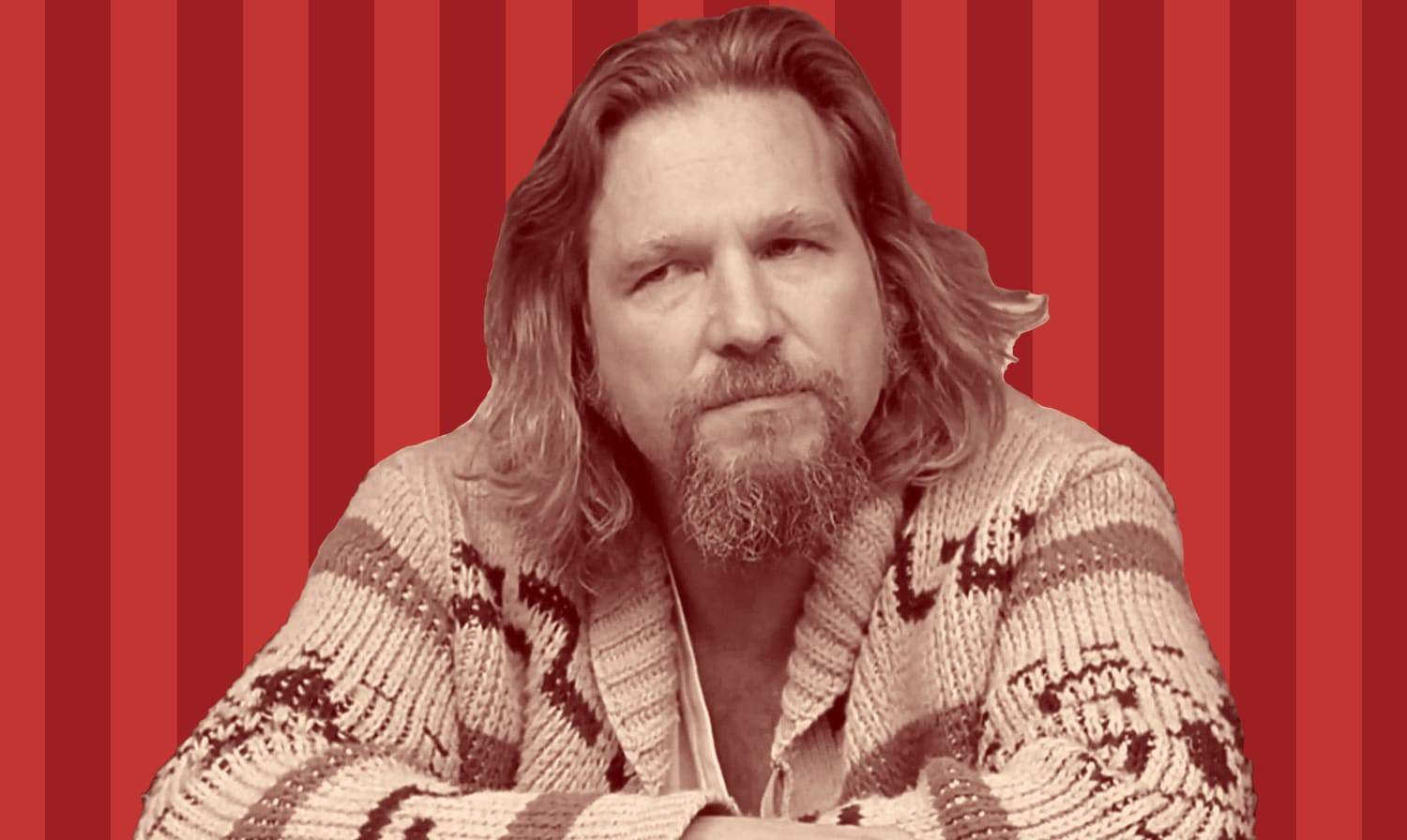

So let’s turn away from the money pits and the awards winners — Oscar verdicts frequently look foolish in retrospect, anyway — and get to the heart of the matter. Because one of the most distinctive things about 1998 is that, for a single year, it provides examples of established masters at the peak of their craft — Peter Weir’s The Truman Show, Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, Terry Gilliam’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas — up-and-comers solidifying their places as industry icons — the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski — and glimpses of the future. Christopher Nolan made his feature debut with Following, Darren Aronofsky with Pi, Guy Ritchie with Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, Lisa Cholodenko with High Art. Wes Anderson made his sophomore feature, the breakout hit Rushmore. (No matter where you stand regarding his use of other cultures, there’s no arguing that Anderson’s aesthetics and literary-esque quirks have proven hugely influential).

It was a great year for cinematic debuts — Amy Poehler made a brief appearance in Tomorrow Night, Taraji P. Henson in Streetwise, Cillian Murphy briefly graced the screen as Pat the Barman in Sweety Barrett, Vera Farmiga in Return to Paradise, and a trifecta of Jasons showed up — Jason Schwartzman in Rushmore, Jason Segel in Can’t Hardly Wait, and Jason Statham in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Especially with the wisdom of twenty years of hindsight, 1998 stands out as a banner year full of promise, with established talents at the top of their game and their successors taking their first steps towards becoming the powerhouses they are today.

Mulan continued the Disney renaissance. Terrence Malick burst back onto the scene after a 20-year absence with The Thin Red Line. American History X presented what remains one of the most effective and uncompromising looks at recognizing ugliness even when in wears the face of people we love. Mimi Leder helmed the $80 million Deep Impact — which, no, was not a good movie, but the sort of world where women get to helm dumb, big-budget apocalyptic explosion fests too is exactly the sort of place where I want to be. In fact, when you add in Nora Ephron’s You’ve Got Mail, two of the top 15 grossing films of 1998 were directed by women — still nowhere near 50%, but sadly, closer to it than many of the years that have come and gone since.

Look, there have been a lot of great movie years, but what sets 1998 apart from all the rest is balance. A lot of great movie years are lopsided — lots of great drama but no good comedy, or great for blockbusters but bad for independents, and so on and so forth. But 1998 had it all.

Animation had a good year with Mulan, The Prince of Egypt, A Bug’s Life, and Antz.

Period pieces had a strong showing with Shakespeare in Love, Elizabeth, and Gods and Monsters.

Small-budget independent filmmaking continued to have a strong showing with Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo ’66, Todd Solondz’s Happiness, and Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine.

The action genre had The Mask of Zorro, Blade, and Ronin. Romance had a fantastic year with Ever After, You’ve Got Mail, and Shakespeare in Love.

It was a banner year for war films between Saving Private Ryan and The Thin Red Line.

Sci-fi/speculative fiction had a strong presence with The Truman Show, Pi, Blade, and The Faculty.

Non-English language films also had a good year, between Walter Salles’ Central Station (Brazil), Hur Jin-ho’s Christmas in August (South Korea), Erik Skjoldbjærg’s Insomnia, and Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (Germany).

Drama had everything from American History X to Rounders to A Simple Plan to The Truman Show and What Dreams May Come.

And it was a fantastic year for comedy regardless of what kind of humor floats your boat — teen comedy (Can’t Hardly Wait, Rushmore), raunchy rom-com (There’s Something About Mary), sweet rom-com (You’ve Got Mail, The Wedding Singer), buddy cops (Rush Hour), political comedy (Bulworth, Wag the Dog), crime comedy (Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels, Out of Sight), and The Big Lebowski, which defies categorization and is in a class of its own.

I’m not saying 1998 was perfect. It had its fair share of duds, from Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla to a veritable avalanche of lackluster sequels (Blues Brothers 2000, Species II, The Odd Couple II, Halloween H20: 20 Years Later, Babe: Pig in the City). But in terms of cinematic range—of having something for everybody, of presenting a mix of established masters and promising new voices, of displaying a wealth of new ideas and innovative styles—I wish every year could be like 1998.