Ending Explained is a recurring series in which we explore the finales, secrets, and themes of interesting movies and shows, both new and old. This time, we come to a conclusion on the ending of Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival.

The concept of outer space is inherently complicated. In a movie like Ad Astra, the rules of space are constantly questioned. And in law-shattering classics such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Interstellar, those rules are replaced altogether. One element does tend to bind space movies together, though: time. Whether it be a film about astronauts plunging themselves into uncharted areas of the cosmos or an expedition to the moon, one thing is for sure: the laws of time function differently in space.

Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 sci-fi drama Arrival takes the study of time to a new level altogether. Adapting Ted Chiang’s short story “Story of Your Life,” Villeneuve and screenwriter Eric Heisserer take the film as an opportunity to posit what space might be able to teach us about time — via extraterrestrial visitors. Using a subtly abstract narrative structure, they consider what the discrepancy might be between how we have been taught to think about time and how it really exists.

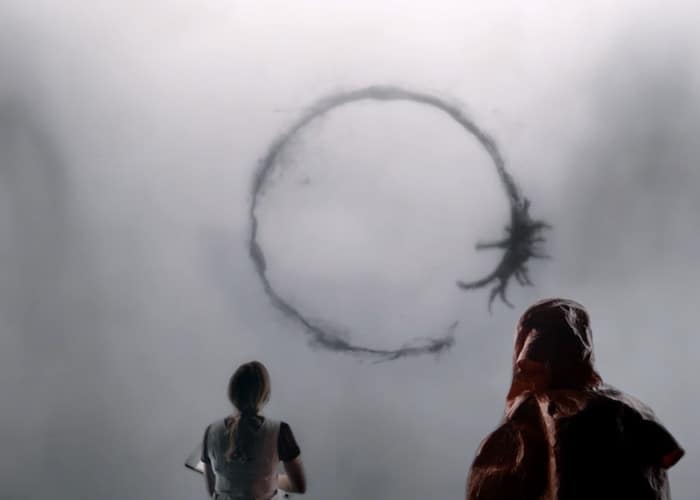

Arrival begins with the news that twelve alien crafts have appeared around the Earth. Esteemed linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams) is recruited by the US military to visit one of the landing sites and make an attempt to communicate with the extraterrestrial beings inside the ship. She teams up with physicist Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner) to research the language of these “Heptapod” creatures, which consists of initially inscrutable palindromes they draw on glass with an inky substance.

By the end of the film, Louise has used her vast linguistic expertise to successfully master the aliens’ vocabulary, and she shares the language key she’s created with similar groups of scientists and soldiers at other sites around the world where the ships have landed. But when one of the Heptapods’ messages is interpreted by the team in China as threatening, that nation’s authorities cut off communication with the visitors, and many other governments follow suit.

The situation spirals out of control from this point. China’s General Shang (Tzi Ma) issues a warning to the Heptapods positioned at his nation’s landing site that their ship must leave… or else. Other countries’ leaders do the same. This is not good, especially as Ian has just made the discovery that every nation’s team needs to share their findings in order for each individual piece of communication to be brought together to reveal the full message from the aliens.

Louise knows it’s vital for the people of Earth to continue the relationship with the Heptapods. Anyone with a proper grasp of the language will no longer see time as being linear. Louise’s visions of her daughter, Hannah, that have been shown throughout the film are revealed to not be memories from the past at all; instead, they’re memories from the future. Hannah’s father, it turns out, is — or will be — Ian. And he will wind up leaving the two of them once he realizes that Louise always knew what was going to happen to their daughter all along and she had her anyway.

Despite this, Louise perseveres. She ensures that humans and aliens can continue to coexist by telling General Shang his wife’s dying words, which Louise only could have learned from meeting him at some point in the future. Once Shang realizes that Louise is telling the truth about the Heptopods’ message, he calls off the war with the creatures. Louise also follows her prophecy and starts a relationship with Ian. They have Hannah. Hannah dies.

To properly understand this complex play with time, one must first be familiar with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or theory of linguistic relativity, which Ian brings up halfway through Arrival. Posited by Edward Sapir in 1929, the theory suggests that the language, or languages, that we know shape our experience of the world. This manifests itself in clear and subtle ways in our society. One popular example is the English language’s categorization of professions by gender, how the distinction between, say, “actor” and “actress” likely informs the way we perceive men and women differently.

In Arrival, though, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is given a whole new meaning. Before Louise fully comprehends the alien language, she is given hints of her own changing mind. The closer she gets to understanding the Heptapods, the more visions she has of Hannah — visions that are still (at least intended to be) presumed by the viewer to be memories. But at the end of the film, Louise asks the creatures “Who is this child?” At that moment, she finally confronts the fact that, indeed, her brain has been rewired, and it has happened through her knowledge of a new language.

But it is not the Heptapods’ job to control the future or have any say in it. They almost act as omniscient beings, who simply give humans the tools to see into the future. Of course, this raises a lot of philosophical questions. Does this new language prove the existence of fate? Or does it simply encourage an existential viewpoint?

The answer is complicated. Ultimately, it’s a bit of both. Although nothing in the film goes against any of the prophecies that Louise has, everything is still ultimately a choice. Before Louise has Hannah, for example, she proposes to Ian: “Let’s have a baby.” Similarly, when General Shang whispers the words in Louise’s ears that he knows will make his past self call off the war, he is doing so because he wants the past to take place exactly as it has. Both of these choices are made independently, just with a greater knowledge of the future.

It is never fully explained why the Heptapods wanted to come to Earth to gift this tool to humankind, but it is likely that they knew it would make for a better world and perhaps a better universe. When it comes to existential creatures like humans, we need all the help we can get with decision-making. And if we know something is going to end up being the right thing, it’ll be easier to do. And when we know something might end in pain but we do it anyway — as in the brief life and death of a daughter — that proves the perseverance of love, fragility, and all of the things that make us human.