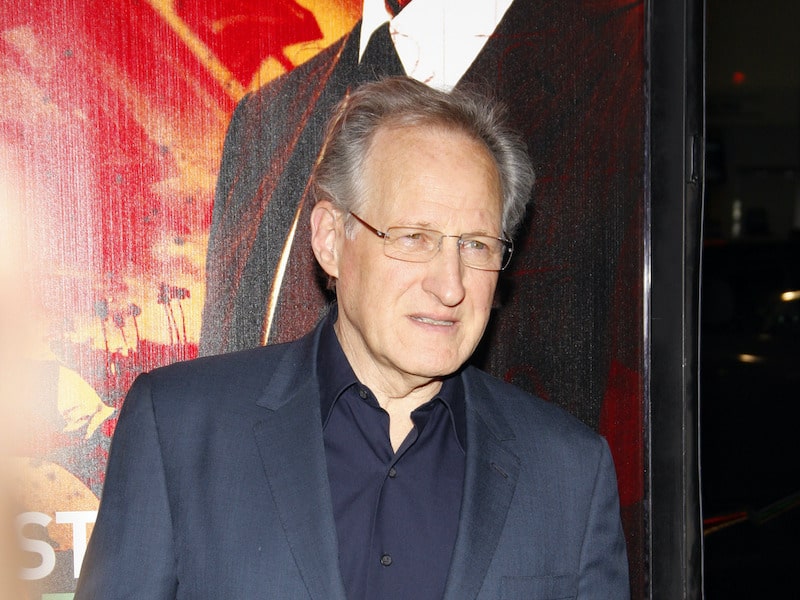

Welcome to Filmmaking Tips, a long-running column in which we gather up the shared knowledge of a particular filmmaker and assemble it all into the internet’s favorite thing: a list. This one is about the filmmaking of Michael Mann.

Michael Mann’s films are sexy, cool, gritty, slick, angry, and sometimes neon. He’s a filmmaker who is often eager to teach us the true meaning of heartache, and plenty of ’80s and ’90s kids owe professional directing careers to his stylistic pathfinding. Not to mention everyone who loved Drive.

He’s also a frustrating director because his output is relatively infrequent (eleven movies in thirty-four years), yet he’s greatly consistent in the kinds of stories that he reaches for. Men, usually desperate, always driven, reaching for something far beyond themselves. Exploring that ground has yielded some truly excellent cinematic experiences and killer moments over the past three decades.

So here’s a bit of free film school (for filmmakers and fans alike) from a man who likes playing with shadows.

The filmmaking lessons we can learn from Ken Burns

1. It takes a lot to get to Thief

The Criterion’s synopsis of Mann’s debut feature (spine #691), begins, “The contemporary American auteur Michael Mann burst out of the gate, his bold artistic sensibility fully formed, with Thief, his debut feature.”

That’s a bold, completely accurate statement that could be encouraging for aspiring filmmakers, but is more likely to be bleak as an unlit L.A. alleyway at midnight. Unless you know that Mann wasn’t sprung clean from William Friedkin’s head ‐ he was already well-seasoned as a filmmaker before taking a shot at the big screen.

He earned a graduate degree from the London Film School and worked in England throughout the 1960s, worked on TV shows including Starsky and Hutch and Police Story, as well as shot a made-for-TV movie. After that, he then, finally, shot his first theatrical feature.

There’s no quote directly from Mann about paying dues or anything, but his career trajectory is an impressive, important corrective to the narrative that he was perfect right out of the gate.

2. Let details win over angst

“To be confident or lacking confidence didn’t enter the equation that much. Of course there was some anxiety, but I wanted to make the film for so long ‐ I had written it, researched it and had Thief all over. We were so living in that world, that it never … it may have occurred to me a little bit before the first night of shooting, you know, ‘Wait a minute. Should I be a little apprehensive?’ [Laughs]

But I was too busy worrying about it, and familiar with every aspect of the film, rehearsals, location scouting, to have the luxury of self-reflection and anxiety. You know, you are making a movie three months before you start shooting. So, it became: is that crane going to show up? Because, on our first day shooting, I have to do this crane shot down through Rat Alley. It was the first shot of the film. The rainmakers aren’t working. I want parallel rain so I’m not really worried about, ‘Should I have an anxiety attack or not?’” [Laughs]

Again, this if from a director who had a lot of professional notches on his belt before setting Frank loose on the safes of the world, but there’s a great lesson here about preoccupation and how worthwhile it can be. One of the most striking elements of Mann’s filmmaking is his obsessive attention to detail, and that shows through in his technique as well as the captured image. He’d lived in a criminal narrative for decades before this project, but he also knew, intimately, every inch of Thief before arriving to the set on the first day of shooting. He had less time to let his subconscious go to work on an Impostor Complex because he was spending all of it worried about making fake rain.

3. When given the chance, make a prototype

In one sense, it’s difficult to imagine many filmmakers getting an opportunity like this. Mann made L.A. Takedown in 1989 for very little money and very little expectation (there’s another weird lesson here about the guy who made Heat making a TV movie three years before making Last of the Mohicans ‐- at least in a time without Netflix and prestige TV).

He got to effectively remake the story a few years later as Heat, this time with more money and more on the line. Can you imagine being able to find out a story’s flaws by making it before making it? Not easy to imagine unless you’re willing to take the time to make a raw cut for as little money as possible in order to test the script you’re working on. Which probably isn’t a terrible idea.

4. Think of research concretely

“As part of the curriculum designed for an actor getting into character, I try to imagine what’s going to really help bring this actor more fully into character. And so I try to imagine what experiences are going to make more dimensional his intake of Frank, so that he is Frank spontaneously when I’m shooting. So one of the most obvious things is it’d be pretty good if [James Caan] was as good at doing what Frank does as is Frank.”

Mann had thieves as consultants on Thief, which seems a little shocking in that is-he-allowed-to-do-that? way but also totally appropriate given the movie’s title. If your main character is a thief, you might want him to learn how to do the things a thief would, right? That could only enhance the script and provide authenticity (which can be huge for production value), regardless of whether the character is doing something illegal, teaching, plumbing or being a professional pool shark.

5. A good story doesn’t need a subtext statement

Graham Fuller: Are you trying to make any contemporary political statements yourself?

Michael Mann: No. [Last of the Mohicans’] attraction lies in making a passionate and vivid love story in a war zone. To make that period feel real means making dramatic forces out of the political forces of this time, which also fascinated me. The politics are functional to the story-telling, as is the visual style. I didn’t want to take 1757, this story, and turn it into some kind of two-dimensional metaphor for 1991. What I did want to do was go the other way and take our understanding of those cultures ‐ and I think we understand them better today than Cooper did in 1826 ‐ and use our contemporary perspective as a tool to construct a more intense experience of realistically complex people in a complex time.

Sorry, deep readers and hot takers.

6. But sometimes good scenes do

“I wanted to direct, I tried to direct the subtext [in The Insider]. That’s where I found the meaning of the scenes. You could write the story of certain scenes in a code that would be completely coherent but have nothing to do with the lines you hear.

For example, in the hotel room scene, Scene 35, when Lowell and Jeffrey first meet: All Lowell knows for sure is that Jeffrey has said “no” to helping him analyze a story about tobacco for “60 Minutes.” He doesn’t know yet that there’s a “yes” hiding behind this “no.” There’s a whole story going on that’s not what anybody’s talking about.”

What we’ve learned about filmmaking

Sometimes I feel stupid for thinking that Mann is a tough director to pin down. His movies are all on the same shelf in the video store, and they so often deal with themes of masculinity in the context of war, crime, and violence, but I also bristle a little when people define him so narrowly. After all, this is a director who only makes a movie every few years because he’s waiting on the right project, the one that sings to him, which relates to his own vision of evolving his understanding of storytelling.

At the same time, there’s a straightforwardness about him to be admired. He’s found outstanding moments between characters by injecting stories with dramatic irony, and the crime element is almost always natural for increasing tension, but what’s really impressive is his patience and confidence in allowing moments to breathe. To reveal themselves in different ways slowly without losing overall momentum. That’s the mark of a careful planner and a prepared filmmaker who knows every inch of every element inside and out.

Correction: In an earlier version of this article, we asserted that Mann was the showrunner on Miami Vice (1984–1990) and Crime Story (1986–1988) before making Thief in 1981. We regret the error. Please don’t force us to drive you around while you kill people for money.

Related Topics: Filmmaking Tips