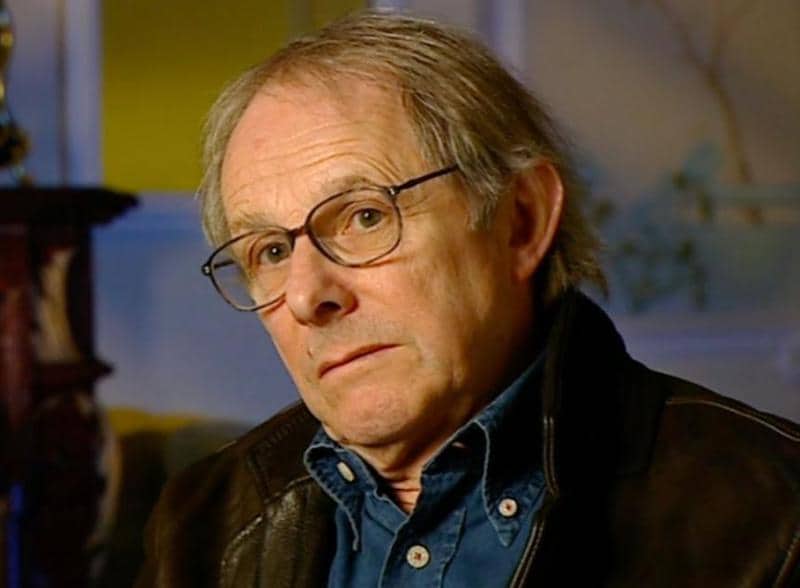

Last month, Ken Loach won his second Palme d’Or with his latest feature, I, Daniel Blake. He was only the ninth filmmaker to pull a double with this prestigious top Cannes Film Festival prize (he previously won in 2006 with The Wind That Shakes the Barley), and he also now has the distinction of being the oldest filmmaker to receive the award.

This week, he advances another year to turn 80. For his birthday, we have a gift for you: advice on making movies from a master with more than half a century’s worth of significant work, including classics of the British cinema movement known as kitchen sink realism such as Kes and Poor Cow.

If you want more tips, there’s sure to be some in a new documentary on the man, Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach, which recently opened in the UK and will hopefully head elsewhere soon, as well as its forthcoming spinoff for French and German TV titled How to Make a Ken Loach Film. Otherwise, we’ve compiled six essentials below.

Capture Spontaneous Performances

One of the great things about Loach is he shares all of his secrets. In a 2013 interview with Mentorless, he dispenses eight tips, which we’re condensing into just one big piece of advice for the sake of this column’s economy. It’s really just eight parts to one major point, anyway: for realistic performances, you need to be spontaneous with actors to get spontaneous reactions.

He insists on shooting in sequence, as difficult and costly as that can be and not sharing the whole script with actors, let alone doing read throughs or lengthy advance rehearsals. This way you can keep the actors in the moment and on the level of their characters in terms of what they know and don’t know. Here he stresses the surprise factor:

We’ve developed a method of not giving the full script at the beginning. The important thing is that the performer has to know everything about the past of the character, so you can’t surprise them with something from their past because that’s not helpful. But for something they have no control over in the future, then, if it’s a surprise, then you have to shoot the surprise. You have to shoot the shock. Because even the most talented actor will have trouble being shocked twice. Because the timing of that is so instinctive, to reproduce it is almost impossible. I’ve worked with fantastic actors, and that’s the hardest thing, surprise. So if there is a surprise, you’ve got to shoot the surprise, which means you can’t show them the whole script before you start.

On a related note, in an interview from 2014 [no longer available], Loach makes a point of directors being responsible for getting the performances out of actors without indulging them.

Don’t Try to Be Both a Writer and a Director

Another interview from the same time, this one with Filmmaker magazine, similarly offers a bunch of tips from Loach, all of them worth checking out. One of the most interesting among the 10, however, is his distinction between writers and directors. Unlike most auteurs, Loach doesn’t pen the scripts for his own films, not even as a co-writer.

He certainly collaborates with his screenwriters ‐ in this interview he says the relationship between writer and director is sacred ‐ but not enough to earn a credit for them. Here is why he’s a director but not a writer:

If you’re a director, remember you’re not a writer. I think a lot of directors coming in now think they have to be the writer as well, and I think that’s the biggest handicap, you know? If you’re a director, you’re not a writer. And if you’re a writer, you’re probably not a director. Remember the distinction.

There are not a lot of good director/writers. Usually the script is too thin. It’s not complex enough, and it’s not deep enough. For a writer who directs, it’s usually too dense. They don’t allow it to breathe.

You need different visions coming in and they’re not the same; they’re complementary. It’s good that there’s another eye on the script and there’s another eye on the directing.

Start in the Theatre

Loach also stresses the importance of collaboration and each job being its own creative piece in a 2011 fan Q&A video for the British Film Institute. One of questions concerns advice for young people just leaving film school. He states that not everyone needs to try to be a director. But if you do want to be a director, he says to start in the theatre.

“You can only learn [how to work with actors] when you’re not hiding behind the camera,” he says. Watch the rest below.

Social Realism Shouldn’t Be Dour

Coming from kitchen sink drama and continuing to make politically tinged social realist films, Loach is often mistakenly perceived as being too serious, and audiences expect his movies to be grim in tone or just boring. But many of them do involve humor, and it’s not just to “sweeten the pill.” He commented on the comedic elements of his films last month to the National Post:

Often people write stories about people who are suffering, and they’re miserable all the time. That’s not the case. You go to the food bank or wherever and there’s laughter, there’s comedy, there’s stupidity, there’s silliness and warmth. And that’s the reality of people’s lives. If you cut out that sense of humor and warmth, you miss the point.

In an excerpt from the 2006 documentary Carry On Ken below he talks about funny situations being a part of real life:

When You’re Older, Make Documentaries

Considering his age and how long he’s been making movies, Loach may not actually be the best person to give advice to young filmmakers. He does what suits him at this time in his life and career. And in recent years, he’s gone from being known for using documentary techniques in his films to wanting to make actual documentaries (despite his earlier experiences with his nonfiction films being censored or banned), such as the acclaimed 2013 feature The Spirit of ’45. He has teased retirement, but only from fiction.

Loach told The Guardian in 2014:

With documentary, you observe something that you haven’t set up. Jimmy’s Hall is set in Ireland in the ‘30s and everything that went under the camera we had to generate. With documentaries you don’t have to do that. And archive documentaries are the best of all because the film just arrives in the cutting room! And you do the odd interview or two, which is always nice. So archive documentary is basically the genre of choice for the senior director.

Stick Two Fingers Up

Finally, the most important piece of advice from Loach is to buck the system ‐ political and commercial. His films are known for being political in content (again, to the point of censorship), but his thoughts on the film business, versus film art, are even more noteworthy for other directors to consider if they want to follow his ways of working.

He specifically says, “You want to stick two fingers up,” when talking about the idea of going to Hollywood to make a movie in a 2011 interview with Empire. Ten years earlier, on BBC Radio 4’s Today show, he trashed his fellow British filmmakers who go to work for the mainstream American industry:

I think it’s time British filmmakers stopped allowing themselves to be colonized so ruthlessly by US ideas and stopped looking so slavishly to the US market. It demeans filmmaking when they do that. The climate generally in Britain is to make films that look across the Atlantic and I think that’s disastrous. It means our own culture gets devalued and it’s as though there has to be an American in everything.

In the below video, Loach tells a French audience why it’s important especially for non-American filmmakers to go up against the American mainstream cinema, and if you’re headed there or anywhere else abroad to do so only to share your own story, not their version of your story.

What We Learned

Loach has a long career and has done a lot of interviews and has never been shy about how he works, what he makes films about, or why. This is just a short list representing who he is and what he has to share in terms of advice and filmmaking philosophy. Some of the rest can be found in the interviews linked to or embedded above, as well as plenty of others done in the last 50 years, some of which are featured in the book “Loach on Loach.”

As for what we’ve learned here specifically, some of the key things to remember are the importance of collaboration (he believes the director, writer, and producer are a kind of holy trinity but respects the crafts of everyone involved in a film), letting performances come about naturally, maintaining a truthful balance of comedy and drama, and going against the grain, though only for honest reasons.

And start out in theatre, as he did (albeit as an actor) and end as a documentarian. Or don’t. Here’s possibly the most important piece of advice he can give filmmakers, from a 2001 interview with Venice magazine (reposted at The Hollywood Interview):

Don’t take advice. You have to make up your own mind what to do from the beginning. Don’t follow the industry ritual. Follow your own voice. The industry practice, I think, is very damaging, very sterile.

Check out the new trailer for Loach’s new film, hitting theaters this fall:

Related Topics: Documentary, Filmmaking, Filmmaking Tips