Welcome to Filmmaking Tips, a long-running column in which we gather up the shared knowledge of a particular filmmaker and assemble it all into the internet’s favorite thing: a list. This one compiles advice from David O Russell.

When assessing what present and future filmmakers can learn from David O. Russell’s ideas and practices, it really depends on which David O. Russell we’re talking about. Is it David O. Russell the mad genius auteur, who was as notorious for insisting on his vision as he was for getting in much-publicized spats with actors on set? Or is it David O. Russell the comeback king who, with this weekend’s American Hustle, seems all but guaranteed a third critically lauded and commercially successful film in a row?

In several notable ways, the themes of David O. Russell’s films haven’t changed all that much ‐ he’s still as preoccupied as ever with depicting various types of dysfunctional, untraditional, and ultimately affirming oddball “families” ‐ but his filmmaking has changed greatly, a switch that he chalks up to lessons learned from the troubled shoot and reception of (the still-underrated) I Heart Huckabees as well as his unfinished film Nailed. Whatever you think of Russell’s films, he’s found himself in a position to speak about filmmaking from an encyclopedia of experiences (good and bad) and attitudes (egotistical to humble).

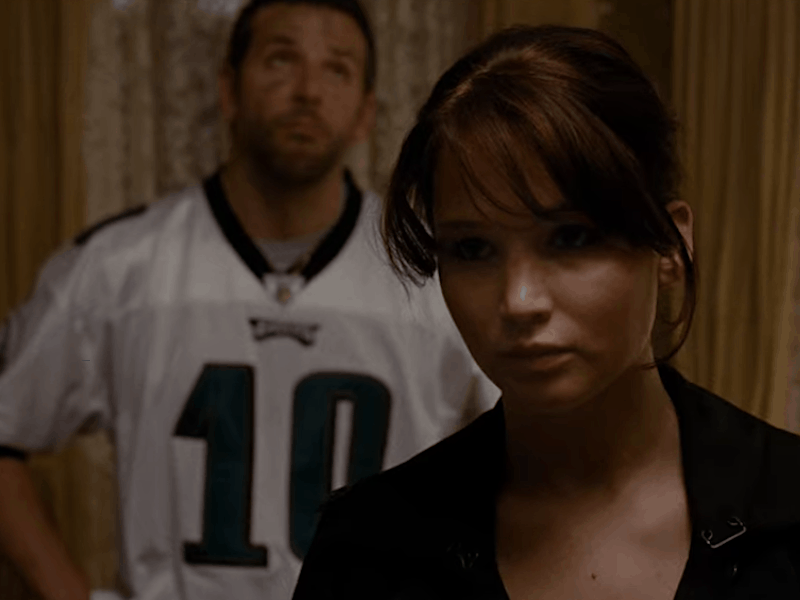

So here’s a bit of free film school (for fans and filmmakers alike) from the guy who got Bruce Wayne and Katniss Everdeen their first Oscars.

The filmmaking lessons we can learn from David O. Russell

1. There Is Such a Thing as Being Too Driven

“I still feel like I’m sill learning. My greatest struggle as a failure in any way was losing my own way. In this business you can be given enough rope to hang yourself…you start over-thinking things or trying to make things too interesting or become too particular and no project feels right…I over-thought what I was going to do next and had my head up my ass on [I Heart Huckabees]…I would have been above [The Fighter during that period].”

This quote speaks directly to the two Russells I mentioned ‐ here the present thoughtful Russell seeking to make good movies and please crowds wrestles with the former self-obsessed artist. When I first wrote about this quote after it appeared at a Hollywood Reporter roundtable last year, it struck me as a bit depressing to see a filmmaker is defining the worth of his work according to the limits of what Hollywood finds palatable. And Russell might be so burned by his past experiences that this is undeniably the case.

But while I’m thankful that there still exist filmmakers that do over-think things (and thankful for the first half of Russell’s filmography), there’s a pragmatism here that’s necessary to wrestle with. What Russell is essentially talking about is shedding the idealism of a lone artist pose in order to face the reality that one is working in a collaborative medium with a lot of shared investment. Filmmaking is, by its very design, an environment of conflict. As the director, you can choose to manage that conflict and use the system toward your advantage in order to make a good movie, or you can make the system (and everyone within it) your enemy.

2. Comedy and Tragedy Come from the Same Place

Interview Magazine: “How did you convey both the drama and humor in mental illness [in Silver Linings Playbook]?”

Russell: “From the sublime to the tragic to the ridiculous. It wasn’t that far from The Fighter’s Christian Bale character, who is hilarious, and that’s how that character is in real life. If you love these people, they are funny. You marvel at them. Sometimes you want to kill them and are astonished at what’s happening and then they create tragedy. It’s how I see everything, which is why I probably never will do a movie that simply feels bad.”

Russell seems to have mastered a certain type of screwball comedy ‐ a type that readily blends broad laughs and clever quips with dark subjects like suicidal tendencies, incest, drug addiction, and existential crises. That the opening of Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (his funniest film) alludes to Howard Hawks’s Bringing Up Baby shows that Russell knows who he’s indebted to. But he’s also accomplished something seriously different with the genre: he’s shown the connection between comedy and the dark underside of life. Comedy is no antonym for seriousness or synonym for levity; it can reveal profound and unpalatable truths with greater clarity than overdetermined “drama.”

3. Craftsmanship Wins Over Preciousness

Russell’s self-critical/grandiose dichotomy of directorial personalities speaks to the duality of his past and present career. Early in this interview, Russell refers to himself as a slow learner who is just now getting the hold on how to make a good film. He stresses here the vital importance of taking feedback from others, something that’s difficult if not impossible in the grandiose posture. You’d think a filmmaker so interested in families and communities would know from the get-go that open communication is key.

4. Trick Yourself Into Voyeurism

Interview Magazine: “How did you maintain the realism in [Silver Linings Playbook]?”

Russell: “The whole trick is to make it feel like you’re spying on real people’s lives as they get through the day. When I’m writing, I have to trick myself as a writer. If I consciously say, “I’m writing,” I feel all this pressure and somehow it doesn’t feel as real as when it doesn’t seem to count as much. When I write an email where I outlined a whole scene, it just came out of my unconscious, it comes from a deeper place. The same thing happens when the actors go, take after take, and just get lost in it. When you’re in a house, you don’t think about being in the house; you’re just there. You trick yourself into being in the moment, and then it’s just happening and you feel like you’re a voyeur on this world.”

5. Get Dirty to Be Happy

“It took me years of writing feature scripts to discover my metier. It was only by going into the most embarrassing and disturbing parts of myself that I came up with this. I felt very happy then. I felt like I’d found something I could talk about.”

Taken from an interview with The Independent in promotion of his film Spanking the Monkey ‐ the “incest comedy” with which he made his name in the seemingly limitless world of ’90s American indie filmmaking ‐ Russell’s statement points to the liberating potential of embracing taboo topics. The happiness described here doesn’t point to a desire for sensationalism or the exploitative, but an urge to explore topics that are fascinating and important particularly because they are verboten. The incest in Spanking the Money isn’t a punchline ‐ the punchline is what such a controversial subject reveals about family and human relationships. Take present Russell’s self-criticism with a grain of salt, as past Russell has some important pearls of wisdom.

6. Films are Vulnerable, and Nothing is Guaranteed

During the considerable gap between 2004 and 2010, during which time Russell produced no new features after the underperformance of Huckabees, Russell encountered something that directors fear most: a film going unfinished. Reportedly most if not all of Nailed was shot before the production went bankrupt, but the fact that even a Jake Gyllenhaal-starring film can sit on the shelf untouched for years speaks to the vulnerability of filmmaking as a practice and a business, especially outside of studios during this uncertain economic moment. It’s a helpful reminder that nothing is guaranteed in such a complicated field, and nothing should be taken for granted.

What we’ve learned about filmmaking

If Nailed does see the light of day (and it actually might), it will be interesting to see what type of bridge it constructs between past and present Russell. The film sounds well-aligned with the screwball work of his early career, but it is likely also imbued with the palpable humanism that drives his overall body of work and manifests a clear thread between Spanking the Monkey and Silver Linings Playbook.

Of course, the truth is, there are not two David O. Russells. The Russell that directed Christian Bale and Jennifer Lawrence toward Oscar statues is the same Russell that notoriously argued with George Clooney and Lily Tomlin during production. The Russell that directed two consecutive $100 million-plus grossing Best Picture nominees is the same Russell who made a film that (to date) has never seen the light of day. Russell’s career is evidence that our work not only changes with and is subject to certain circumstances largely outside of our control, but more importantly that filmmakers also grow as human beings as they develop their craft. Filmmaking is a learning process, and Russell’s career and work attest to that fact loud and clear.

Related Topics: Filmmaking